5 Annotations Every Java Developer Should Know

In this article, we will take a look at 5 of the annotations supported by all Java compilers and take a look at their intended uses.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeSince their inception in Java Development Kit (JDK) 5, annotations have become an indispensable part of the Java ecosystem. While there are countless custom annotations developed for use by Java frameworks (such as @Autowired for Spring), there are a few annotations recognized by the compiler that are of supreme importance. In this article, we will take a look at 5 of the annotations supported by all Java compilers and take a look at their intended uses. Along the way, we will explore the rationale behind their inception, some idiosyncrasies that surround their use, and some examples of their proper application. Although some of these annotations are more common than others, each should be internalized by non-beginner Java developers. To start off, we will delve into one of the most commonly used annotations in Java: @Override.

@Override

The ability to override the implementation of a method, or provide an implementation for an abstract method, is at the core of any Object-Oriented (OO) language. Being that Java is an OO language and features many of the common OO abstraction mechanisms, a non-final method defined in a non-final superclass or any method in an interface (interface methods cannot be final) can be overridden by a subclass. Although overriding a method appears to be straightforward at first, there are many subtle bugs that can be introduced when overriding is performed incorrectly. For example, it is a common mistake to override the Object#equals method with a single parameter of the type of the overriding class:

public class Foo {

public boolean equals(Foo foo) {

// Check if the supplied object is equal to this object

}

}Being that all classes implicitly inherit from the Object class, the intent of our Foo class is to the override the Object#equals method so that Foo can be tested for equality against any other object in Java. While our intent is correct, our implementation is not. In fact, our implementation does not override the Object#equals method at all. Instead, we provide an overload of the method: rather than substituting the implementation of the equals method provided by the Object class, we instead provide a second method that accepts Foo object specifically, rather than an Object object. Our mistake can be illustrated using the trivial implementation that returns true for all equality checks but is never called when the supplied object is treated as an Object (which Java will do, such as in the Java Collections Framework, JCF):

public class Foo {

public boolean equals(Foo foo) {

return true;

}

}

Object foo = new Foo();

Object identicalFoo = new Foo();

System.out.println(foo.equals(identicalFoo)); // falseThis is a very subtle, but common error that could be caught by the compiler. It was our intent to override the Object#equals method, but because we specified a parameter of type Foo, rather than type Object, we in fact provided overloaded the Object#equals method, rather than overriding it. In order to catch mistakes of this kind, the @Override annotation was introduced, which instructs the compiler to check if an override was actually performed. If a valid override was not performed, an error is thrown. Thus, we can update our Foo class to resemble the following:

public class Foo {

@Override

public boolean equals(Foo foo) {

return true;

}

}If we try to compile this class, we now receive the following error:

$ javac Foo.java

Foo.java:3: error: method does not override or implement a method from a supertype

@Override

^

1 errorIn essence, we have transformed our implicit assumption that we have overridden a method into an explicit verification by the compiler. In the event that our intent was incorrectly implemented, the Java compiler will emit an error, not allowing our code with our incorrect implementation to successfully compile. In general, the Java compiler will emit an error for a method annotated with @Override if either of the following conditions is not satisfied (quoted from the Override annotation documentation):

- The method does override or implement a method declared in a supertype.

- The method has a signature that is override-equivalent to that of any public method declared in

Object(i.e.equalsorhashCodemethods).

Therefore, we can also use this annotation to ensure that a subclass method actually overrides a non-final concrete method or abstract method in a superclass as well:

public abstract class Foo {

public int doSomething() {

return 1;

}

public abstract int doSomethingElse();

}

public class Bar extends Foo {

@Override

public int doSomething() {

return 10;

}

@Override

public int doSomethingElse() {

return 20;

}

}

Foo bar = new Bar();

System.out.println(bar.doSomething()); // 10

System.out.println(bar.doSomethingElse()); // 20The @Override annotation is not relegated to just concrete or abstract methods in a superclass, but can also be used to ensure that methods of an interface are overridden as well (since JDK 6):

public interface Foo {

public int doSomething();

}

public class Bar implements Foo {

@Override

public int doSomething() {

return 10;

}

}

Foo bar = new Bar();

System.out.println(bar.doSomething()); // 10In general, any method that overrides a non-final concrete class method, an abstract superclass method, or an interface method can be annotated with @Override. For more information on valid overrides, see the Overriding and Hiding documentation and section 9.6.4.4. of the Java Language Specification (JLS).

@FunctionalInterface

With the introduction of lambda expressions in JDK 8, functional interfaces have become much more prevalent in Java. These special types of interfaces can be substituted with lambda expressions, method references, or constructor references. According to the @FunctionalInterface documentation, a functional interface is defined as follows:

A functional interface has exactly one abstract method. Since default methods have an implementation, they are not abstract.

For example, the following interfaces are considered functional interfaces:

public interface Foo {

public int doSomething();

}

public interface Bar {

public int doSomething();

public default int doSomethingElse() {

return 1;

}

}Thus, each of the following can be substituted with a lambda expression as follows:

public class FunctionalConsumer {

public void consumeFoo(Foo foo) {

System.out.println(foo.doSomething());

}

public void consumeBar(Bar bar) {

System.out.println(bar.doSomething());

}

}

FunctionalConsumer consumer = new FunctionalConsumer();

consumer.consumeFoo(() -> 10); // 10

consumer.consumeBar(() -> 20); // 20It is important to note that abstract classes, even if they contain only one abstract method, are not functional interfaces. For more information on this decision, see Allow lambdas to implement abstract classes written by Brian Goetz, chief Java Language Architect. Similar to the @Override annotation, the Java compiler provides the @FunctionalInterface annotation to ensure that an interface is indeed a functional interface. For example, we could add this annotation to the interfaces we created above:

@FunctionalInterface

public interface Foo {

public int doSomething();

}

@FunctionalInterface

public interface Bar {

public int doSomething();

public default int doSomethingElse() {

return 1;

}

}If we were to mistakenly define our interfaces as non-functional interfaces and annotated the mistaken interface with the @FunctionalInterface, the Java compiler would emit an error. For example, we could define the following annotated, non-functional interface:

@FunctionalInterface

public interface Foo {

public int doSomething();

public int doSomethingElse();

}If we tried to compile this interface, we would receive the following error:

$ javac Foo.java

Foo.java:1: error: Unexpected @FunctionalInterface annotation

@FunctionalInterface

^

Foo is not a functional interface

multiple non-overriding abstract methods found in interface Foo

1 errorUsing this annotation, we can ensure that we do not mistakenly create a non-functional interface that we intended to be used as a functional interface. It is important to note that interfaces can be used as the functional interfaces (can be substituted as lambdas, method references, and constructor references) even when the @FunctionalInterface annotation is not present, as we saw in our previous example. This is analogous to the @Override annotation, where a method can be overridden, even if it does not include the @Override annotation. In both cases, the annotation is an optional technique for allowing the compiler to enforce our intent.

For more information on the @FunctionalInterface annotation, see the @FunctionalInterface documentation and section 4.6.4.9 of the JLS.

@SuppressWarnings

Warnings are an important part of any compiler, providing a developer with feedback about possibly dangerous behavior or possible errors that may arise in future versions of the compiler. For example, using generic types in Java without their associated formal generic parameter (called raw types) causes a warning, as does the use of deprecated code (see the @Deprecated section below). While these warnings are important, they may not always be applicable or even correct. For example, there may be instances where a warning is emitted for an unsafe type conversion, but based on the context in which it is used, it can be guaranteed to be safe.

In order to ignore specific warnings in certain contexts, the @SuppressWarnings annotation was introduced in JDK 5. This annotation accepts 1 or more string arguments that represent the name of the warnings to ignore. Although the names of these warnings generally vary between compiler implementation, there are 3 warnings that are standard in the Java language (and hence are common among all Java compiler implementations):

unchecked: A warning denoting an unchecked type cast (a typecast that the compiler cannot guarantee is safe), which may occur as a result of access to members of raw types (see JLS section 4.8), narrow reference conversion or unsafe downcast (see JLS section 5.1.6), unchecked type conversions (see JLS section 5.1.9), the use of generic parameters with variable arguments (varargs) (see JLS section 8.4.1 and the@SafeVarargssection below), the use of invalid covariant return types (see JLS section 8.4.8.3), indeterminate argument evaluation (see JLS section 15.12.4.2), unchecked conversion of a method reference type (see JLS section 15.13.2), or unchecked conversation of lambda types (see JLS section 15.27.3).deprecation: A warning denoting the use of a deprecated method, class, type, etc. (see JLS section 9.6.4.6 and the@Deprecatedsection below).removal: A warning denoting the use of a terminally deprecated method, class, type, etc. (see JLS section 9.6.4.6 and the@Deprecatedsection below).

In order to ignore a specific warning, the @SuppressedWarning annotation, along with 1 or more names of suppressed warnings (supplied in the form of a string array), can be added to the context in which the warning would occur:

public class Foo {

public void doSomething(@SuppressWarnings("rawtypes") List myList) {

// Do something with myList

}

}The @SuppressWarnings annotation can be used on any of the following:

- type

- field

- method

- parameter

- constructor

- local variable

- module

In general, the @SuppressWarnings annotation should be applied to the most immediate scope of the warning. For example, if a warning should be ignored for a local variable within a method, the @SuppressWarnings annotation should be applied to the local variable, rather than the method or the class that contains the local variable:

public class Foo {

public void doSomething() {

@SuppressWarnings("rawtypes")

List myList = new ArrayList();

// Do something with myList

}

}@SafeVarargs

Varargs can be a useful technique in Java, but they can also cause some serious issues when paired with generic arguments. Since generics are non-reified in Java, the actual (implementation) type of a variable with a generic type cannot be determined at runtime. Since this determination cannot be made, it is possible for a variable to store a reference to a type that is not its actual type, as seen in the following snippet (derived from Java Generics FAQs):

List ln = new ArrayList<Number>();

ln.add(1);

List<String> ls = ln; // unchecked warning

String s = ls.get(0); // ClassCastException After the assignment of ln to ls, there exists a variable ls in the heap that has a type of List<String> but stores a reference to a value that is actually of type List<Number>. This invalid reference is known as heap pollution. Since this error cannot be determined until runtime, it manifests itself as a warning at compile time and a ClassCastException at runtime. This issue can be exacerbated when generic arguments are combined with varargs:

public class Foo {

public <T> void doSomething(T... args) {

// ...

}

}In this case, the Java compiler internally creates an array at the call site to store the variable number of arguments, but the type of T is not reified and is therefore lost at runtime. In essence, the parameter to doSomething is actually of type Object[]. This can cause serious issues if the runtime type of T is relied upon, as in the following snippet:

public class Foo {

public <T> void doSomething(T... args) {

Object[] objects = args;

String string = (String) objects[0];

}

}

Foo foo = new Foo();

foo.<Number>doSomething(1, 2);If executed, this snippet will result in a ClassCastException, because the first Number argument passed at the call site cannot be converted to a String (similar to the ClassCastException thrown in the standalone heap pollution example. In general, there may be cases where the compiler does not have enough information to properly determine the exact type of a generic vararg parameter, which can result in heap pollution. This pollution can be propagated by allowing the internal varargs array to escape from a method, as in the following example from pp. 147 of Effective Java, 3rd Edition:

public static <T> T[] toArray(T... args) {

return args;

}In some cases, we know that a method is actually type safe and will not cause heap pollution. If this determination can be made with assurance, we can annotate the method with the @SafeVarargs annotation, which suppresses warnings related to possible heap pollution. This begs the question, though: When is a generic vararg method considered type safe? Josh Bloch provides a sound answer on pp. 147 of Effective Java, 3rd Edition, based on the interaction of a method with the internally created array used to store its varargs:

If the method doesn’t store anything into the array (which would overwrite the parameters) and doesn’t allow a reference to the array to escape (which would enable untrusted code to access the array), then it’s safe. In other words, if the varargs parameter array is used only to transmit a variable number of arguments from the caller to the method—which is, after all, the purpose of varargs—then the method is safe.

Thus, if we created the following method (from pp. 149 Ibid.), we can soundly annotate our method with the @SafeVarags annotation:

@SafeVarargs

static <T> List<T> flatten(List<? extends T>... lists) {

List<T> result = new ArrayList<>();

for (List<? extends T> list : lists) {

result.addAll(list);

}

return result;

}For more information on the @SafeVarargs annotation, see the @SafeVarargs documentation, JLS section 9.6.4.7, and Item 32 from Effective Java, 3rd Edition.

@Deprecated

When developing code, there may be times when code becomes out-of-date and should no longer be used. In these cases, there is usually a replacement that is better suited for the task at hand and while existing calls to the out-dated code may remain, all new calls should use the replacement method. This out-of-date code is called deprecated code. In some pressing cases, deprecated code may be slated for removal and should be immediately converted to the replacement code before a future version of a framework or library removes the deprecated code from its code base.

In order to support the documentation of deprecated code, Java includes the @Deprecated annotation, which marks some constructor, field, local variable, method, package, module, parameter, or type as being deprecated. If this deprecated element (constructor, field, local variable, etc.) is used, the compiler will emit a warning. For example, we can create a deprecated class and use it as follows:

@Deprecated

public class Foo {}

Foo foo = new Foo();If we compile this code (in a file called Main.java), we receive the following warning:

$ javac Main.java

Note: Main.java uses or overrides a deprecated API.

Note: Recompile with -Xlint:deprecation for details.In general, a warning will be thrown whenever an element annotated with @Deprecated is used, except in the following five circumstances:

- The use is within a declaration that is itself deprecated (i.e. a recursive call).

- The use is within a declaration that is annotated to suppress deprecation warnings (i.e. the

@SuppressWarnings("deprecation")annotation, described above, is applied to the context in which the deprecated element is used). - The use and declaration are both within the same outermost class (i.e. if a class calls its own deprecated method).

- The use is within an

importdeclaration that imports the ordinarily deprecated type or member (i.e. when importing a deprecated class into another class). - The use is within an

exportsoropensdirective.

As previously mentioned, there are some cases when a deprecated element is slated for removal and calling code should immediately remove the deprecated element (called terminally deprecated code). In this case, the @Deprecated annotation can be supplied with a forRemoval argument as follows:

@Deprecated(forRemoval = true)

public class Foo {}Using this terminally deprecated code now results in a more imposing set of warnings:

$ javac Main.java

Main.java:7: warning: [removal] Foo in com.foo has been deprecated and marked for removal

Foo foo = new Foo();

^

Main.java:7: warning: [removal] Foo in com.foo has been deprecated and marked for removal

Foo foo = new Foo();

^

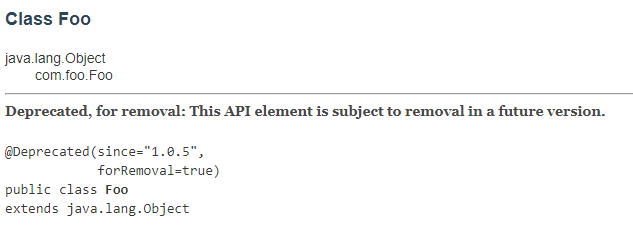

2 warningsTerminally deprecated warnings are always emitted, save for the same exceptions described for the standard @Deprcated annotation. We can also add documentation to the @Deprecated annotation by supplying a since argument to the annotation:

@Deprecated(since = "1.0.5", forRemoval = true)

public class Foo {}Deprecated elements can be further documented using the @deprecated JavaDoc element (note the lowercase d), as seen in the following snippet:

/**

* Some test class.

*

* @deprecated Replaced by {@link com.foo.NewerFoo}.

*

* @author Justin Albano

*/

@Deprecated(since = "1.0.5", forRemoval = true)

public class Foo {}The JavaDoc tool will then produce the following documentation:

For more information on the @Deprecated annotation, see the @Deprecated documentation and JLS section 9.6.4.6.

Coda

Annotations have been an indispensable part of Java since their introduction in JDK 5. While some are more popular than others, there are 5 annotations that any developer above the novice level should understand: @Override, @FunctionalInterface, @SuppressWarnings, @SafeVarargs, and @Deprecated. While each has its own unique purpose, the aggregation of these annotations make a Java application much more readable and allow the compiler to enforce some otherwise implicit assumptions about our code. As the Java language continues to grow, these tried-and-true annotations will likely see many more years of service and help to ensure that many more applications behave as their developers intended.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments