| Pattern |

Migrate using these small, safe steps: Define scope > Migrate branches > Migrate infrastructure > Set cutover date > Commit to Git |

| Anti-pattern |

Migrate everything at once, defining a freeze period until the migration is completed |

DON'T migrate your code in a single step. This can sound easy at first, but poorly planned initial migration can damage your repos and branches considerably.

Step 1: Define migration scope correctly

Take some time to define the scope of what is being migrated to Git. Rarely migrate "everything" – a large mass of stable code history, happily residing in your current VCS, will just weigh down what should be a lean tool. Basically:

DON'T migrate dead repositories and branches (unless you have independent reasons to decommission your legacy VCS, e.g. licensing restrictions)

DO wield a judicious change-depth knife, carefully defining a maximum depth of changes in your branches' history to migrate

Remember that the migration process itself has to physically create every intermediate file status and store all snapshot trees in the Git repository. This operation may take a considerable amount of time, and large chunks of change history may be unhelpful, given your current pipeline.

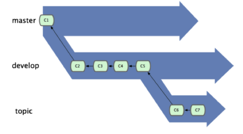

Step 2: Migrate branches

Here's some good news: Git provides out-of-the-box commands for migrating from Subversion (git svn) and CVS (git cvsimport). And now the bad news: these out-of-the-box commands can take a long time to run, so you may need to repeat the process if you don't want to block the productivity of your team.

DO use scripts to run the migration again and again. This will (a) help you predict execution times and (b) fine-tune the list of branches and repositories that you intend to migrate.

Step 3: Migrate build infrastructure

Continuous Integration (CI) and Continuous Delivery (CD) frameworks like Jenkins makes are not tied to any particular VCS. But adding a VCS to your release mix can tangle CI / CD processes significantly. For example, your release process may contain a lot of existing VCS hardcoded commands that need to be changed manually.

DO duplicate existing scripts and declare a script freeze on the original versions until the Git migration is completed.

Step 4: Define a cutover date

Rigorously avoid cutover creep on a project-by-project basis.

DON'T force the entire company into a single cutover date. It's much better to start with a few projects, get feedback on the transition while other projects are still getting ready to migrate, and improve the process for projects with later cutover dates.

DO set migration projects to read-only at cutover so that developers can then commit to Git only. Otherwise, you'll risk stranding a few straggler-projects in an old release paradigm.

Furthermore, the early-migrating teams will have developed expertise and confidence with Git when the later-migrating teams are just getting started – which will help the earlier team-members serve as Git champions (see Pattern #3).

Step 5: Commit to Git!

But just in case:

DO keep a backup of your existing VCS system and its build running until all projects are running on Git flawlessly. Migrating once is hard enough and more depressing when the direction is backward.

DEFINE your roll-back procedure – you may run into unpredictable problems, such as people misusing the tool or with your Git Server or Build stability, and you must not let this interfere with your productivity. Insofar as the first Git migration attempt damages productivity, the next migration attempt is unlikely to happen.

Hybrid VCS

Throughout the migration process you need to manage more than one system at a time (i.e. legacy Subversion and the new Git repositories).

You may consider as well, though not suggested, to keep some of the projects in your legacy VCS, because of their complex project history or their rather excessive cost to migrate consolidated (or end-of-life) project maintenance to a different system.

DO use proper tools (i.e. CollabNet TeamForge or SubGit) to make sure that you are able to manage both tools during migration in a consistent way.