EBNF: How to Describe the Grammar of a Language

Learn the basics of EBNF, the most commonly used formalism to describe the structure of programming languages, and how to use it in practice.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeEBNF is the most commonly used formalism to describe the structure of languages.

In this article, we are going to see:

- What EBNF is.

- Examples of grammars defined with EBNF.

- How we can define a grammar using EBNF.

- A few things to consider when using EBNF.

- How to use EBNF in practice today.

- A summary with some final thoughts.

Does it sound like a plan?

What Is EBNF?

EBNF is a way to specify a formal language grammar. It can be considered a metalanguage because it is a language to describe other languages

A formal language is a language with a precise structure, like programming languages, data languages, or Domain Specific Languages (DSLs). Java, XML, and CSS are all examples of formal languages.

A grammar can be used to define two opposite things:

- How to recognize the different portions in a piece of code written in the formal language.

- The possible ways to build a valid piece of code in the formal language.

For example, a simple grammar could tell us that a document in our language is composed by a list of declarations, and declarations are defined by the sequence of a keyword Xyz and a a name.

Based on this, we could:

- Recognize in the code sequences of the keyword Xyz and a name as instances of these declarations we have considered.

- We could generate valid documents in our language by writing a list of declarations, each time inserting a keyword Xyz and a name.

While there are two possible usages for a grammar, we are typically interested only in the first one: recognizing if a piece of code is valid for a given language and identifying the different structures typical of the language (like functions, methods, classes, etc.).

What EBNF Means

Okay, but what does EBNF stand for? EBNF stands for Extended Backus-Naur Form. It will not surprise you to read that it is an extended version of the Backus-Naur form (BNF).

There is at least one other format derived from BNF, which is called ABNF, or Augment Backus-Naur Form. ABNF's main purpose is to describe bidirectional communications protocols. EBNF is the most used one.

While there is a standard for EBNF, it is common to see different extensions or slightly different syntaxes to be used. In the rest of the article, we will add more comments when looking at specific parts of EBNF.

Examples of EBNF Grammars

We are going to see some examples of grammars taken from a list available on GitHub. Later, we could refer to them while explaining the rules.

Note also that for each language, you could have different equivalent grammars. So for the same language, you could find grammars which are not exactly the same, and yet they are correct anyway.

An EBNF grammar for HTML:

htmlDocument

: (scriptlet | SEA_WS)* xml? (scriptlet | SEA_WS)* dtd? (scriptlet | SEA_WS)* htmlElements*

;

htmlElements

: htmlMisc* htmlElement htmlMisc*

;

htmlElement

: TAG_OPEN htmlTagName htmlAttribute* TAG_CLOSE htmlContent TAG_OPEN TAG_SLASH htmlTagName TAG_CLOSE

| TAG_OPEN htmlTagName htmlAttribute* TAG_SLASH_CLOSE

| TAG_OPEN htmlTagName htmlAttribute* TAG_CLOSE

| scriptlet

| script

| style

;

htmlContent

: htmlChardata? ((htmlElement | xhtmlCDATA | htmlComment) htmlChardata?)*

;

htmlAttribute

: htmlAttributeName TAG_EQUALS htmlAttributeValue

| htmlAttributeName

;

htmlAttributeName

: TAG_NAME

;

htmlAttributeValue

: ATTVALUE_VALUE

;

htmlTagName

: TAG_NAME

;

htmlChardata

: HTML_TEXT

| SEA_WS

;

htmlMisc

: htmlComment

| SEA_WS

;

htmlComment

: HTML_COMMENT

| HTML_CONDITIONAL_COMMENT

;

xhtmlCDATA

: CDATA

;

dtd

: DTD

;

xml

: XML_DECLARATION

;

scriptlet

: SCRIPTLET

;

script

: SCRIPT_OPEN ( SCRIPT_BODY | SCRIPT_SHORT_BODY)

;

style

: STYLE_OPEN ( STYLE_BODY | STYLE_SHORT_BODY)

;An EBNF grammar for TinyC:

program

: statement+

;

statement

: 'if' paren_expr statement

| 'if' paren_expr statement 'else' statement

| 'while' paren_expr statement

| 'do' statement 'while' paren_expr ';'

| '{' statement* '}'

| expr ';'

| ';'

;

paren_expr

: '(' expr ')'

;

expr

: test

| id '=' expr

;

test

: sum

| sum '<' sum

;

sum

: term

| sum '+' term

| sum '-' term

;

term

: id

| integer

| paren_expr

;

id

: STRING

;

integer

: INT

;

STRING

: [a-z]+

;

INT

: [0-9]+

;

WS

: [ \r\n\t] -> skip

;TinyC is a simplified version of C. We picked it because a grammar for a common programming language would be way too complex to serve as an example. We would typically look at grammars longer than 1,000 lines.

How We Typically Define a Grammar Using EBNF

We define a grammar by specifying how to combine single elements in significant structures. As a first approximation, we can consider single words to be elements. The structures correspond to sentences, periods, paragraphs, chapters, and entire documents.

A grammar tells us what are the correct ways to put together single words to obtain sentences, and how we can progress by combining sentences into periods, periods into paragraphs, and so on until we get the entire document.

EBNF: Terminals and Non-Terminals.

Terminals and Non-Terminals

In the approximation we used, single words correspond to terminals, while all the structures built on top of them (sentences, periods, paragraphs, chapters, and entire documents) correspond to non-terminals.

What Terminals Look Like

Terminals are sometimes also called tokens. They are the smallest block we consider in our EBNF grammars.

A terminal could be either:

- A quoted literal.

- A regular expression.

- A name referring to a terminal definition. This option is not part of the EBNF standard, but it is used very frequently. Typically uppercase names are used for these terminal definitions, to distinguish them from non-terminal definitions. These latter definitions are the proper production rules.

For example, in the grammar, you could use "when" to indicate that exact string. Also, regular expressions are used, like /[a-z]+/. Finally, we could group terminal definitions somewhere and then use their names to refer to them. Using definitions have the advantage of permitting to reuse them multiple times.

Let’s see some typical terminals:

- identifiers: these are the names used for variables, classes, functions, methods and so on. Typically most languages use different conventions for different names. For example in Java class names start with an uppercase letter, static constants are written using all uppercase letters, while methods and variable names start with a lowercase letter. However, these are just best practices: in Java, there is just one type of identifier that can be used everywhere. This is not the case for all the languages. In languages like Haskell, identifiers used for types must start with an uppercase letter. Another thing to consider is that the definition of identifiers typically overlaps with the definitions of keywords. The latter should take precedence. I.e., if a token could be either an identifier or a keyword, then it should be recognized as a keyword.

- keywords: almost every language uses keywords. They are exact strings that are used to indicate the start of a definition (think about

classin Java ordefin Python), a modifier (public,private,static,final, etc.) or control flow structures (while,for,until, etc). - literals: these permit to define values in our languages. We can have string literals, numeric literal, char literals, boolean literals (but we could consider them keywords as well), array literals, map literals, and more, depending on the language.

- separators and delimiters: like colons, semicolons, commas, parenthesis, brackets, braces.

- whitespaces: spaces, tabs, newlines. They are typically not meaningful and they can be used everywhere in your code.

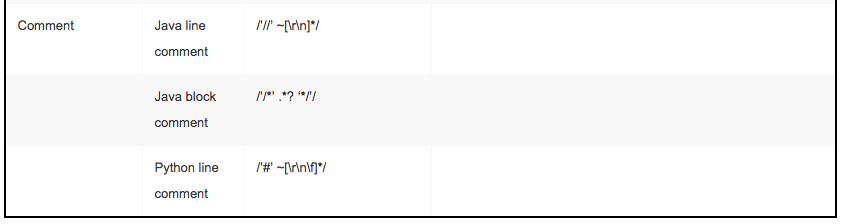

- comments: most languages have one or more ways to define comments and commonly they can be used everywhere. Some languages could have more structured forms of documentation comments.

Whitespaces and comments are typically ignored in EBNF grammars. This is because usually they could be used everywhere in the language, so they should be reported all over the grammar. Some tools have specific options to mark some terminals as terminals to ignore.

How Terminals Are Defined

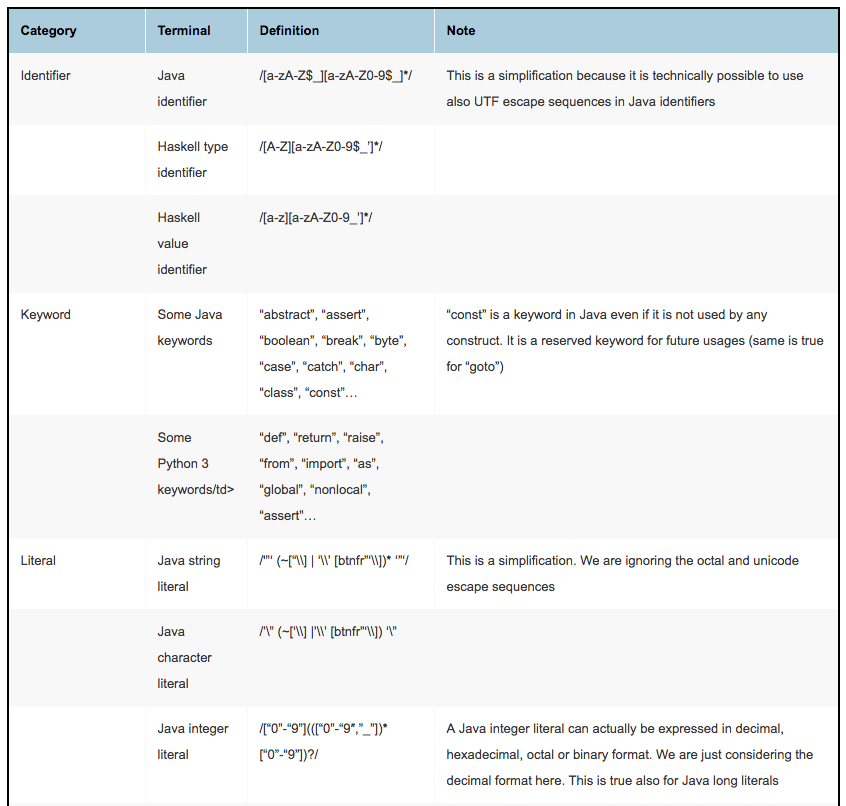

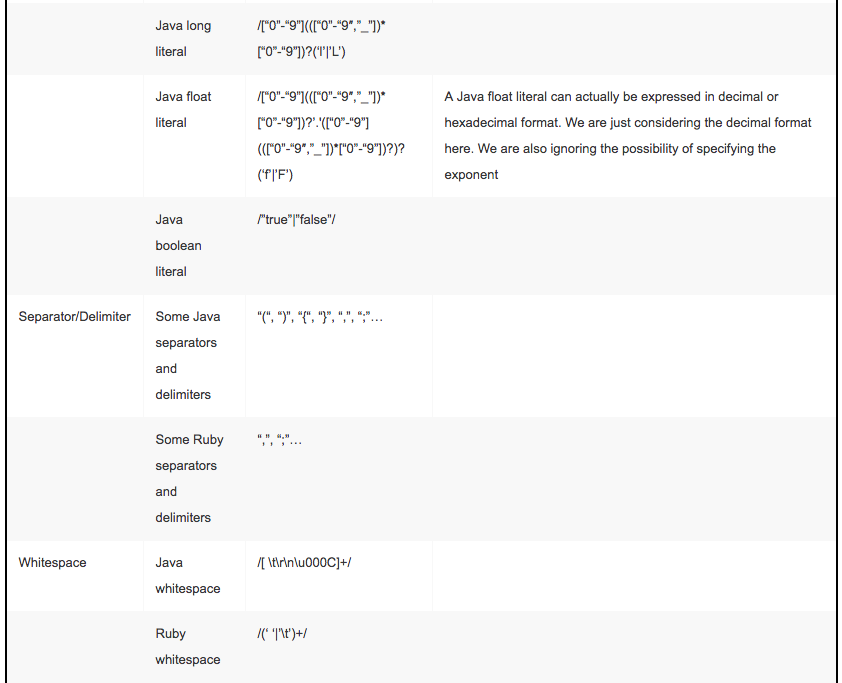

Terminals are defined using string constants or regular expressions. Let’s see some typical definitions.

What Non-Terminals Look Like

Non-terminals are obtained by grouping terminals and other non-terminals in a hierarchy. After all, our goal is to obtain an Abstract Syntax Tree, which is a tree. Our tree will have a root: one non-terminal representing our entire document. The root will contain other non-terminals that will contain other non-terminals and so on.

The picture below shows how we can go from a stream of tokens (or terminals) to an AST, which groups terminals into a hierarchy of non-terminals.

EBNF - From stream of tokens to AST.

In the grammar, we will define the parser rules that determine how the AST is built.

We have seen that non-terminals represent structures at different levels. Examples of non-terminals are:

- program/document: represent the entire file.

- module/classes: group several declarations together.

- functions/methods: group statements together.

- statements: these are the single instructions. Some of them can contain other statements. For example, the loops have a body which is a list of other statements.

- expressions: are typically used within statements and can be composed in various ways.

How are non-terminals defined? We are going to see in the next section.

Definition of Production Rules

An EBNF grammar is substantially a list of production rules. Each production rule tells us how a non-terminal can be composed. We are now going to see the different elements that we can use in such rules.

Terminal

We have seen that a terminal can be defined in-line, specifying a string or a regular expression, or can be defined elsewhere and simply referred to in a rule. The latter method is not technically part of EBNF, but it is commonly used.

expr

: test

| id '=' expr // '-' is a terminal

;

id

: STRING // STRING is a terminal, it is in uppercase

;Refer to a Non-Terminal

Similarly to references to terminals we can also refer to non-terminals. However, this can lead to left-recursive rules that are typically forbidden. For more details see the paragraph on recursion in grammars.

expr

: test

| id '=' expr // id is a non-terminal referred in the expr production rule

;

id

: STRING

;Sequence

A sequence is simply represented by specifying two elements one after the other.

// an htmlAttribute can be created in two ways. The first one requires

// a sequence. First we need to find an htmlAttributeName, then the

// TAG_EQUALS and finally an htmlAttributeValue

htmlAttribute

: htmlAttributeName TAG_EQUALS htmlAttributeValue

| htmlAttributeName

;It is also called concatenation, and in the standard EBNF commas are used between elements, while typically you just use spaces to separate the elements of the sequence.

Alternative

There are some constructs, or portions of constructs, that can be defined in different ways. To represent this case we use alternatives. The different alternatives are separated by the pipe sign (“|“)

// There are different ways to create a statement

statement

: 'if' paren_expr statement // 1st alternative

| 'if' paren_expr statement 'else' statement // 2nd alternative

| 'while' paren_expr statement // 3rd alternative

| 'do' statement 'while' paren_expr ';' // 4th alternative

| '{' statement* '}' // 5th alternative

| expr ';' // 6th alternative

| ';' // 7th alternative

;

// Alternatives are typically used at the top level of production rules

// but this is not always the case. In htmlDocument they are used within

// a sequence

htmlDocument

: (scriptlet | SEA_WS)* xml? (scriptlet | SEA_WS)* dtd? (scriptlet | SEA_WS)* htmlElements*

;Optional (Zero or One Time)

An element can appear zero or one time. In other words, it can be optional.

// both occurences of htmlChardata are optional

htmlContent

: htmlChardata? ((htmlElement | xhtmlCDATA | htmlComment) htmlChardata?)*

;In the standard EBNF, optional elements are represented inside square brackets. However, it is more common to find them represented by a question mark following the optional element.

Zero or More Times

An element can appear zero or more times (no upper limit).

// In three of these alternatives the htmlAttribute can appear

// as many times as we want.

htmlElement

: TAG_OPEN htmlTagName htmlAttribute* TAG_CLOSE htmlContent TAG_OPEN TAG_SLASH htmlTagName TAG_CLOSE

| TAG_OPEN htmlTagName htmlAttribute* TAG_SLASH_CLOSE

| TAG_OPEN htmlTagName htmlAttribute* TAG_CLOSE

| scriptlet

| script

| style

;In the standard EBNF, optional elements are represented inside curly brackets. However, it is more common to find them represented by an asterisk following the element to repeat.

One or More Time

An element can appear one or more times (no upper limit).

// We need at least one statement. We could have just one, or more

program

: statement+

;In this example, we are saying that a program should have at least one statement.

This is not present in standard EBNF, however, this is equivalent to a sequence in which the same element is present twice, and the second time, it is followed by an asterisk so that the same element is effectively present always at least once.

Grouping

We can group multiple elements together by using round parenthesis. This is typically used because a modifier (optional, zero-or-more, one-or-more) must be applied to a set of elements. It can also be used to control the precedence of operators.

// script is defined as a sequence of the terminal SCRIPT_OPEN

// and the group ( SCRIPT_BODY | SCRIPT_SHORT_BODY)

script

: SCRIPT_OPEN ( SCRIPT_BODY | SCRIPT_SHORT_BODY)

;Without using the grouping we would have an alternative between the sequence of SCRIPT_OPEN SCRIPT_BODY(first alternative) and SCRIPT_SHORT_BODY (second alternative).

A Few Things to Consider

We have seen what constructs we can use to define production rules. Now let’s dive into some aspects that we should consider when writing grammars.

Recursion in Grammars: Left or Right?

EBNF lets us define recurring grammars. Recurring grammars are grammars that have recurring production rules, i.e., production rules that refer to themselves and they do so at the beginning of the production rule (left recurring grammars) or at the end (right recurring grammars).

Left recurring grammars are more common. Consider this example:

expression: INT

| expression PLUS expression

;This production rule is left recurring because the expression could start with… an expression.

The fact is that many tools that process EBNF grammars cannot deal with that because they risk entering infinite loops. There are ways to refactor left recurring rules, however, they lead to less clear grammars. So, if you can, just use modern tooling that deals with left and right recurring grammars.

Precedence

Precedence could refer to two things: precedence in the EBNF grammar (i.e., in which order operators in grammars are applied) and precedence in the languages defined by EBNF.

This is very important because it would permit to interpret correctly expressions like:

1 + 2 * 3In this case, we all know that the multiplication has precedence on the addition. In the languages, we are going to define we can have many different rules and we need to define a specific order to consider them.

Let’s talk about the second one.

The traditional way to manage precedence is to define a list of different rules that refers to each other. At the top level, we will have the more abstract rules, like expression, at the bottom level we will have rules representing the smallest components, like a single term. The typical example is shown in TinyC:

expr

: test

| id '=' expr

;

test

: sum

| sum '<' sum

;

sum

: term

| sum '+' term

| sum '-' term

;

term

: id

| integer

| paren_expr

;The grammar as it is defined makes first parse single terms (id, integer, or expressions between parenthesis). Later this can be possibly combined using the plus or the minus sign. Then the less than the operator can be used and this can be part of an expression, the top level rule considered.

This is a relatively simple example but in richer languages we could have 7-12 intermediate rules like test and sum, to represent different groups of operators with the same precedence. The thing about the multiplication, division, power, comparison operators, logical operators, array access, etc. There are many possible ways to build expressions and you need to define an order of precedence.

Now, some modern tools use just the order in which alternatives are defined to derive the precedence rules. For example, in ANTLR, you could write the previous example like:

expr

: id '=' expr

| expr '<' expr

| expr '+' expr

| expr '-' expr

| id

| integer

| paren_expr

;Typical Pattern: Defining Lists

A typical thing we want to define in an EBNF grammar is a list.

We have a list of parameters, a list of variables...all sorts of lists.

Typically we have a separator between elements (like a COMMA). We could have lists that must have at least one element and lists which can have zero elements. Let’s take a look at how we can implement both:

myListOfAtLeastOneElement:

element (COMMA element)*

;

myListOfOfPotentiallyZeroElements:

(element (COMMA element)*)?

;Syntactic vs. Semantic Validity

We have seen that the EBNF can be used to define a grammar, we should consider that a grammar defines what is syntactically valid, but it tells us nothing about what is semantically valid.

What does it mean? Consider these examples:

- A document containing multiple declarations of elements with the same name.

- A sum of two variables: an integer and a boolean.

- A reference to a variable that was not declared before.

We can imagine a language where all these examples are syntactically correct, i.e., they are built according to the grammar of the language. However, they are all semantically incorrect, because they do not respect additional constraints on how the language should be used. These semantics constraints are used in addition to the grammar after the structures of the language have been recognized. In the grammar, we can say things like a declaration should be composed by a certain keyword and a name, with semantic constraints we can say two declarations should not have the same name. By combining syntactic and semantic rules we can express what is valid in our language.

How do you define semantic rules? By writing code that works on the AST. You cannot do that in the EBNF grammar.

Where to Go From Here

An EBNF grammar is useful to support discussion and to communicate with other langue designers. Typically you may want to do more with it: you want to build actual parsers and tools to process languages from your EBNF grammars. I personally like to work with ANTLR. My suggestion is to take a look at the ANTLR Mega Tutorial.

You could be interested in learning more about parsing. We have prepared different articles explaining how to proceed depending on the language you prefer to work with:

And if you are lost and unsure about how to move forward just let us know.

Summary

In this article we aimed to be practical: we have discussed what is done in practice and what you need to start writing grammars using EBNF. We have discussed the differences between typical usages and the standard and tried to give a complete and correct picture.

There are things we did not discuss: for example, the history that leads to the creation of EBNF or its roots in the work of Chomsky and other scientists. We have not discussed what a context-free grammar is. The theory tells us that EBNF cannot be used to describe all possible forms of grammars. However, it is powerful enough to describe all formal languages you should be interested in writing.

Published at DZone with permission of Federico Tomassetti, DZone MVB. See the original article here.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments