DevOps and SRE, Chapter 3: Models for Cultural Change

The third post in this series discusses some of the methods for cultural transformation, as well as the way tools are used to affect change in enterprises.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For Free This is how change happens

This is how change happens

Cloud-native applications are a type of complex system that depends on the continuous effort of software professionals that combines the best of their expertise to keep them running. In other words, their reliability isn't self-sustaining, but is a result of the interactions of all the different actors engaged in their design, build, and operation.

Over the years the collection of those interactions has been evolving together with the systems they were designed to maintain, which have been also becoming increasingly sophisticated and complex. The IT service management model, once designed to maintain control and stability, is now fading and giving place to a model designed to improve velocity while maintaining stability. Although the combination of those things might seem contradictory at first, this series of articles tries to reveal the reasons why the collection of practices that today we know as DevOps and SRE (Site Reliability Engineering) are becoming the norm for modern systems.

You may also enjoy: A Day in the Life of an SRE

Table of Contents:

- Chapter 1 - When innovation becomes mainstream (released: 12/09/2019)

- Chapter 2 - How to cope with complexity (released:12/09/2019)

- Chapter 3 - Models for cultural change (this document)

- Chapter 4 - How innovation becomes mainstream (coming soon)

- Chapter 5 - Accelerate: The Science of Lean Software and DevOps (coming soon)

- Chapter 6 - Signals of change (coming soon)

- to be continued ...

Chapter 3: Models for Cultural Change

In my humble opinion, one of the most inspiring success cases for cultural transformation is the venture between Toyota and GM, back in 1984, in a joint adventure to transform the Fremont manufacturing plant. NUMMI (New United Motor Manufacturing, Inc.) operated from the 1980s until 2010 and represented a tremendous success reference on how to successfully implement the TPS (Toyota Production System).

What really caught my attention on NUMMI's case was the fact that the manufacturing plant, earlier considered the worst reference possible for GM, both in terms of employee engagement and product quality, became best in class in only one year. The story for this transformation was nicely told in the MIT Sloan Management Review whitepaper: How to Change a Culture: Lessons from NUMMI, by John Shook. This is an absolute must-read for those interested in understanding how to embrace a new culture at scale.

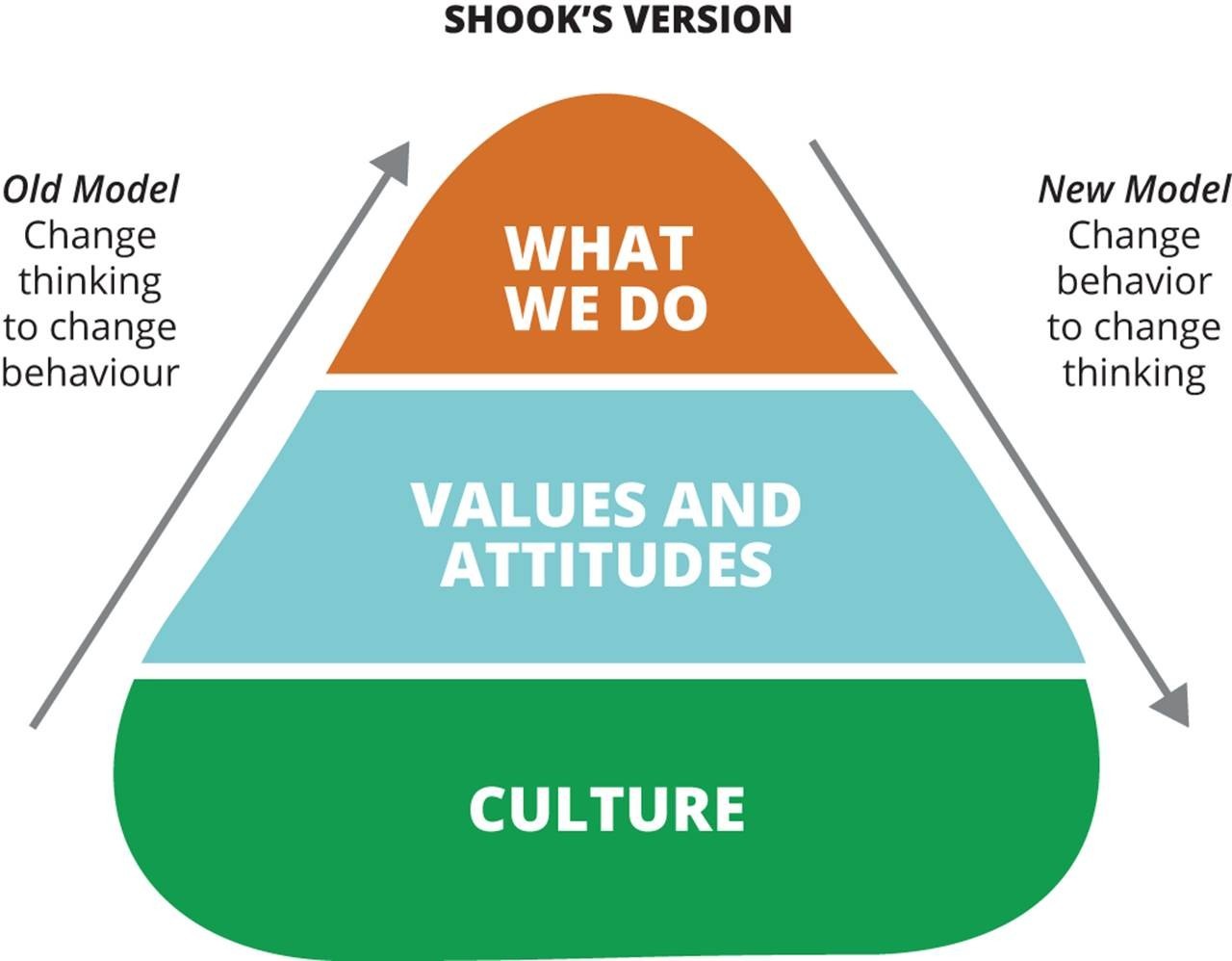

"It's easier to act your way into a new way of thinking than to think your way into a new way of acting." — John Shook

The traditional western approach to change culture has always been an attempt to change the way people think and how they behave and with that, change the way people act. What was observed in the case of NUMMI and later also proved right in other situations, is that the downhill approach is far more effective than the uphill alternative. Changing culture doesn't have to be something abstract and hard to describe. The shared beliefs and rituals that, put together, form our organizational culture, are changed as a consequence of what we do every single day. The key lesson from NUMMI was that to change the culture you need to change the way people do their jobs and, to effectively accomplish that, you need to enable people to thrive. More specifically, you will need to provide the training and the tools that will make them successful in performing their jobs.

As I've always been an enthusiast of the Lean movement and have continually studied the Toyota Production System since college, it was pretty natural to me to believe in the model developed by John Shook (Figure 3), which, just for the sake of reference if the reader is willing to dig into the theory, is structurally similar to Edgar Schein's model, developed several years earlier (1980's). What caught me by surprise was when I, early in 2018, somehow accidentally bumped into a friend and colleague from IBM who experienced a fantastic transformation that I could relate with my personal experiences in IT.

Bill Higgins is an IBM Distinguished Engineer who had spent a few years leading a project that had successfully transformed the way the organization developed software. Such transformation was possible through the massive adoption of lean product and team management combined with the engineering practices around the concept of continuous delivery. Bill wrote two very inspirational articles: Tools as Catalysts for Cultural Change and Listen to The Wild Ducks: How IBM adopted Slack and they describe how IBM successfully engaged people with the appropriate psychographic profile (early adopters and early majority) and helped them succeed in their jobs through the adoption of the right set of tools that reinforced a new collection of modern work practices (LEAN, DevOps, SRE, etc.). While NUMMI's case occurred almost 40 years ago and tells the story of change in the manufacturing era in the automobile industry, IBM's case is current and applied to the technology industry. They are both great examples of cultural change as a result of the change in the way people act and also a demonstration that the model not only survived time but can also be applied to different industries with different technology stacks and processes.

Tools Are Drivers for Cultural Change

The magic is in the new, better practices that the tools enable. A tool is a vehicle for practices. Practices directly shape habits and tacit assumptions. Habits and tacit assumptions are the foundations of culture. (Bill Higgins)

At the end of the day, the famous PPT method (People, Process, Technology) comes out as an almost universal principle for all things in the enterprise. People perform a specific type of work using processes, very often using technology (tools) to streamline and/or improve the very same processes.

This virtuous cycle where processes drive the use of tools, that by their turn, are developed and continually adjusted to improve the same processes that ignited their use in the first place, is extremely powerful. As a matter of fact, it is very hard to really determine if processes drive the use of technology or vice-versa. What I really believe is that good tooling reinforces best practices and, if we consider the examples of large adoption of these practices at scale on any organization, in every situation there are instances where people only started doing things differently because of the tool. Take the case of Github and the practice of code peer-review as a good example of how the practice embedded in the tool drives its adoption.

For a while, the DevOps movement preached that code peer-review would be more effective than the gated approach defined by the CAB (Change Approval Board) for software-related changes. Chances are that the members of the board would have absolutely no idea about the possible impact of a changeset that had to modify thousands of lines of code, therefore the hypothesis is that having the developer who has a better context, and can actually reason about the code change, reviewing it, could eventually eliminate the CAB approval altogether. The enterprise adoption of peer-review is flourishing and one of the key drivers for its adoption is the large adoption of Github for teams who had adopted the agile model. The platform enables a way to enable peer-review in a way that is easy and is well aligned with the existing operating model (aka. Processes) for this specific type of team (squads).

Although Github was the most influential tool for this practice, there are several other instances where the tool actually drives the change in behavior, take Slack for collaboration, Prometheus and Splunk for observability, Jaeger for distributed tracing and several others. They represent a collection of tools that when deployed at any organization, for enterprise use, has the potential to reinforce new ways of work and as a consequence, help change the culture. A culture that sustains this new reality of highly distributed and complex cloud-native applications.

Key Takeaway

Cultural change is possible and, although it won't happen overnight, it doesn't necessarily require a very long time. NUMMI accomplished a significant change within a year. It doesn't mean that the same will be true in the context of your organization and although I don't believe there's one single correct path to transform, the easiest approach to change the way people work the key to change their culture and tacit assumptions. Practice training, knowledge sharing, and the good tools are, if not the most important things, the key enablers for successful transformation. To effectively change people's way of doing things there's nothing more important than helping them succeed in their jobs.Published at DZone with permission of Ricardo Coelho de Sousa. See the original article here.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments