Static Code Analysis: What It Is? How to Use It?

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For Free

Static code analysis refers to the technique of approximating the runtime behavior of a program. In other words, it is the process of predicting the output of a program without actually executing it.

Lately, however, the term “Static Code Analysis” is more commonly used to refer to one of the applications of this technique rather than the technique itself — program comprehension — understanding the program and detecting issues in it (anything from syntax errors to type mismatches, performance hogs likely bugs, security loopholes, etc.). This is the usage we’d be referring to throughout this post.

“The refinement of techniques for the prompt discovery of error serves as well as any other as a hallmark of what we mean by science.”

- J. Robert Oppenheimer

Outline

We cover a lot of ground in this post. The aim is to build an understanding of static code analysis and to equip you with the basic theory, and the right tools so that you can write analyzers on your own.

We start our journey with laying down the essential parts of the pipeline which a compiler follows to understand what a piece of code does. We learn where to tap points in this pipeline to plug in our analyzers and extract meaningful information. In the latter half, we get our feet wet, and write four such static analyzers, completely from scratch, in Python.

Note that although the ideas here are discussed in light of Python, static code analyzers across all programming languages are carved out along similar lines. We chose Python because of the availability of an easy to use ast module, and wide adoption of the language itself.

How does it all work?

Before a computer can finally “understand” and execute a piece of code, it goes through a series of complicated transformations:

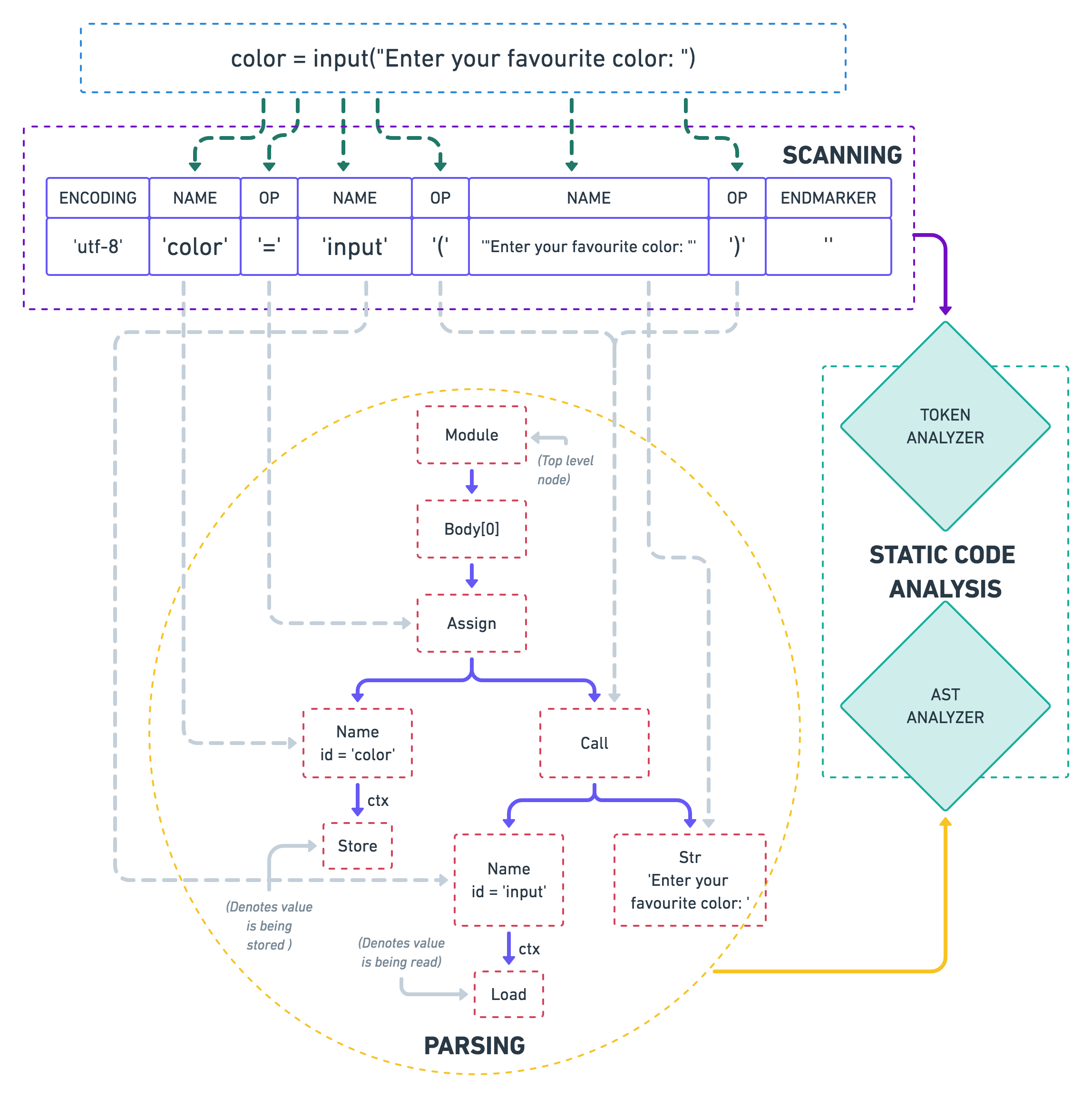

As you can see in the diagram (go ahead, zoom it!), the static analyzers feed on the output of these stages. To be able to better understand the static analysis techniques, let’s look at each of these steps in some more detail:

Scanning

The first thing that a compiler does when trying to understand a piece of code is to break it down into smaller chunks, also known as tokens. Tokens are akin to what words are in a language.

A token might consist of either a single character, like (, or literals (like integers, strings, e.g., 7, Bob, etc.), or reserved keywords of that language (e.g, def in Python). Characters which do not contribute towards the semantics of a program, like trailing whitespace, comments, etc. are often discarded by the scanner.

Python provides the tokenize module in its standard library to let you play around with tokens:

import io

import tokenize

code = b"color = input('Enter your favourite color: ')"

for token in tokenize.tokenize(io.BytesIO(code).readline):

print(token)

xxxxxxxxxx

TokenInfo(type=62 (ENCODING), string='utf-8')

TokenInfo(type=1 (NAME), string='color')

TokenInfo(type=54 (OP), string='=')

TokenInfo(type=1 (NAME), string='input')

TokenInfo(type=54 (OP), string='(')

TokenInfo(type=3 (STRING), string="'Enter your favourite color: '")

TokenInfo(type=54 (OP), string=')')

TokenInfo(type=4 (NEWLINE), string='')

TokenInfo(type=0 (ENDMARKER), string='')

(Note that for the sake of readability, I’ve omitted a few columns from the result above — metadata like starting index, ending index, a copy of the line on which a token occurs, etc.)

Parsing

At this stage, we only have the vocabulary of the language, but the tokens by themselves don’t reflect anything about the grammar of the language. This is where the parser comes into play.

A parser takes these tokens, validates that the sequence in which they appear conforms to the grammar, and organizes them in a tree-like structure, representing a high-level structure of the program. It’s aptly called an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST).

“Abstract” because it abstracts away low-level insignificant details like parenthesis, indentation, etc, allowing the user to focus only on the logical structure of the program — which is what makes it the most suitable choice for conducting static analysis onto.

Analyzing ASTs

A syntax tree can get quite vast and complex, thus making it is difficult to write code for analyzing it. Thankfully, since this is something that all compilers (or interpreters) do themselves, some tooling to simplify this process generally exists.

Python ships with an ast module as a part of its standard library which we’d be using heavily while writing the analyzers later.

If you don’t have prior experience of working with ASTs, here’s how the ast module works:

- All AST node types are represented by a corresponding data structure in the

astmodule, e.g., for loops are characterized by theast.Forobject. - For building an AST from source code, we use the

ast.parsefunction. - For analyzing a syntax tree, we need an AST “walker” — an object to facilitate the traversal of the tree. The

astmodule offers two walkers:ast.NodeVisitor(doesn’t allow modification to the input tree)ast.NodeTransformer(allows modification)

- When traversing a syntax tree, we are generally interested in only analyzing a few nodes of interest, e.g. if we are writing an analyzer to warn us if we have more than 3 nested for loops, we’d only be interested in visiting

ast.Fornodes. - For analyzing a particular node type, the walker needs to implement a special method. This method is often called a “visitor” method. Terminology: to visit a node, then, is nothing but just a call to this method.

- These methods are named as

visit_+<NODE_TYPE>, e.g., to add a visitor for “for loops”, the method should be namedvisit_For. - There’s a top-level

visitmethod which recursively visits the input node, i.e. it first visits itself, then all of its children nodes, then the children nodes of children nodes, and so forth.

Just to give you a sense of how this works, let’s write code for visiting all for loops:

xxxxxxxxxx

import ast

# Demo code to parse

code = """\

sheep = ['Shawn', 'Blanck', 'Truffy']

def get_herd():

herd = []

for a_sheep in sheep:

herd.append(a_sheep)

return Herd(herd=herd)

class Herd:

def __init__(self, herd):

self.herd = herd

def shave(self, setting='SMOOTH'):

for sheep in self.herd:

print(f"Shaving sheep {sheep} on a {setting} setting")

"""

class Example(ast.NodeVisitor):

def visit_For(self, node):

print(f"Visiting for loop at line {node.lineno}")

tree = ast.parse(code)

visitor = Example()

visitor.visit(tree)

This outputs:

xxxxxxxxxx

Visiting for loop at line 5

Visiting for loop at line 14

- We first visit the top level

ast.Modulenode. - Since no visitor exists for that node, by default, the visitor starts visiting its children — the

ast.Assign,ast.FunctionDefandast.ClassDefnode. - Since no visitors exist for them as well, the visitor again starts visiting all their children.

- At some stage, when an

ast.Forloop is finally encountered, thevisit_Formethod is called. Notice, that a copy ofnodeis also passed onto this method — which contains all the metadata about it — children (if any), line number, column, etc.

Python also has several other third-party modules like astroid, astmonkey, astor which provide additional abstract modules to make our lives easier.

But, in this post, we’ll confine ourselves to the barebones ast module so that we get to see the real, ugly operations behind the scenes.

Examples

Although this blog post is only an introduction to static code analysis, we’d be writing scripts to detect issues which are highly relevant in real-world scenarios as well (chances are, that your IDE already warns you if you violate one). This shows just how powerful static code analysis is, and what it enables you to do with so little code:

- Detect any usage of single quotes instead of double-quotes.

- Detect if

list()is used instead of[] - Detect too many nested for loops.

- Detect unused imports in a file.

Here are how the examples would work:

- The names of the files to be analyzed are specified as command line arguments when running the script.

- If an issue is detected, the script should print an appropriate error message on the screen.

Detecting single quotes

Here, we write a script which would raise a warning whenever it detects that single quotes have been used in the Python files given as input.

This example may be considered rudimentary compared to other modern-day static code analysis techniques, but it is still included here because of historical significance — this was pretty much how early code analyzers worked1. Another reason, it makes sense to include this technique here is that it is heavily used by many popular static tools, like black.

xxxxxxxxxx

import sys

import tokenize

class DoubleQuotesChecker:

msg = "single quotes detected, use double quotes instead"

def __init__(self):

self.violations = []

def find_violations(self, filename, tokens):

for token_type, token, (line, col), _, _ in tokens:

if (

token_type == tokenize.STRING

and (

token.startswith("'''")

or token.startswith("'")

)

):

self.violations.append((filename, line, col))

def check(self, files):

for filename in files:

with tokenize.open(filename) as fd:

tokens = tokenize.generate_tokens(fd.readline)

self.find_violations(filename, tokens)

def report(self):

for violation in self.violations:

filename, line, col = violation

print(f"{filename}:{line}:{col}: {self.msg}")

if __name__ == '__main__':

files = sys.argv[1:]

checker = DoubleQuotesChecker()

checker.check(files)

checker.report()

Here’s a breakdown of what is happening:

- Input file names are read as command line arguments.

- These file names are passed on to the

checkmethod, which generates tokens for each file and passes them onto thefind_violationsmethod. - The

find_violationsmethod iterates through the list of tokens and looks for “string type” tokens whose value is either''', or'. If it finds one, it flags the line by appending it toself.violations. - The

reportmethod then reads all the issues fromself.violationsand prints them out with a helpful error message.

xxxxxxxxxx

def simulate_quote_warning():

'''

The docstring intentionally uses single quotes.

'''

if isinstance(shawn, 'sheep'):

print('Shawn the sheep!')

xxxxxxxxxx

example.py:2:4: single quotes detected, use double quotes instead

example.py:5:25: single quotes detected, use double quotes instead

example.py:6:14: single quotes detected, use double quotes instead

Note that for the sake of brevity, error-handling has been omitted entirely from these examples, but needless to say, they are an essential part of any production system.

Boilerplate for Further Examples

The previous example was the only example where we were working directly with tokens. For all others, we’d limit our interaction to the generated ASTs only.

Since a lot of code would be duplicated across these checkers, and this post is already so long, let’s first get some boilerplate code in place, which we can later reuse for all examples. Defining boilerplate code at once also allows me to discuss only relevant details under each checker and get away with all the business logic at once:

xxxxxxxxxx

import ast

from collections import defaultdict

import sys

import tokenize

def read_file(filename):

with tokenize.open(filename) as fd:

return fd.read()

class BaseChecker(ast.NodeVisitor):

def __init__(self):

self.violations = []

def check(self, paths):

for filepath in paths:

self.filename = filepath

tree = ast.parse(read_file(filepath))

self.visit(tree)

def report(self):

for violation in self.violations:

filename, lineno, msg = violation

print(f"{filename}:{lineno}: {msg}")

if __name__ == '__main__':

files = sys.argv[1:]

checker = <CHECKER_NAME>()

checker.check(files)

checker.report()

Most of the code works the same way as we saw in the previous example, except that:

- We have a new function

read_fileto read the contents of the given file. - The

checkmethod, instead of tokenizing, reads the contents of all the file paths one by one and then parses its AST using theast.parsemethod. It then uses thevisitmethod to visit the top-level node (anast.Module) and thereby, all of its children nodes recursively. It also sets the value ofself.filenameto the current file being analyzed — so that we can add the filename in the error message when we find a violation later.

You might notice that there are a couple of unused imports — they’d be used later on. Also, the placeholder <CHECKER_NAME> needs to be replaced with the actual name of the checker class when running the code.

For the entire ready-to-run code for all checkers in this post, see this GitHub Gist

Detecting usage of list()

It is advised to use an empty literal [] instead of list() for an empty list because it tends to be slower — the name list must be looked up in the global scope before calling it. Also, it might result into a bug in case the name list is rebound to another object.

list() resides as an ast.Call node. Thus, we start with defining the visit_Call method for our new ListDefinitionChecker class:

xxxxxxxxxx

class ListDefinitionChecker(BaseChecker):

msg = "usage of 'list()' detected, use '[]' instead"

def visit_Call(self, node):

name = getattr(node.func, "id", None)

if name and name == list.__name__ and not node.args:

self.violations.append((self.filename, node.lineno, self.msg))

Here’s briefly what we’re doing:

- When visiting a

Callnode, we first try to get the name of the function being called. - If it exists, we check whether it is equal to

list.__name__. - If yes, we’re now sure that a call to

list(...)is being made. - Thereafter, we ensure that no arguments are being passed to the

listfunction, i.e. the call being made is indeedlist(). If so, we flag this line by adding an issue.

Running this file on some example code (ensure that you have updated the <CHECKER_NAME> in the boilerplate to ListDefinitionChecker):

xxxxxxxxxx

def build_herd():

herd = list()

for a_sheep in sheep:

herd.append(a_sheep)

return Herd(herd)

xxxxxxxxxx

example.py:2: usage of 'list()' detected, use '[]' instead

Detecting Too Many Nested for Loops

“For loops” which are nested for more than 3 levels are unpleasant to look at, difficult for the brain to comprehend with, and a headache to maintain at the very least.

Thusly, let’s write a check to detect whenever more than 3 levels of nested for loops are encountered.

Here’s what we’d do: We begin counting as soon as an ast.For node is encountered. We also mark this node as a ‘parent’ node. We, then check if any of its children are also ast.For nodes. If yes, we increment the count and repeat the same procedure for the child node again.

xxxxxxxxxx

class TooManyForLoopChecker(BaseChecker):

msg = "too many nested for loops"

def visit_For(self, node, parent=True):

if parent:

self.current_loop_depth = 1

else:

self.current_loop_depth += 1

for child in node.body:

if type(child) == ast.For:

self.visit_For(child, parent=False)

if parent and self.current_loop_depth > 3:

self.violations.append((self.filename, node.lineno, self.msg))

self.current_loop_depth = 0

The workflow might look a little skewed at first, but here’s basically what we’re doing:

- When

visitmethod is called (fromBaseCheckerclass), it starts looking for anyast.Fornodes in the AST. As soon, as it finds one, it calls the methodvisit_Forwith default keyword argumentparent=True. - We use the variable

parentas a flag to track the outermost loop — in which case, we initializeself.current_loop_depthto 1, else, we just increment its value by 1. - We examine the body of this loop to recursively look for any child

ast.Fornodes. If we find one, we callvisit_Forwithparent=False. - When we’re done traversing, we evaluate whether the loop depth has reached beyond 3. If so, we report a violation and reset the loop depth to 0 again.

Let’s run our script on some examples:

xxxxxxxxxx

for _ in range(10):

for _ in range(5):

for _ in range(3):

for _ in range(1):

print("Baa, Baa, black sheep")

for _ in range(4):

for _ in range(3):

print("Have you any wool?")

for _ in range(10):

for _ in range(5):

for _ in range(3):

if True:

for _ in range(3):

print("Yes, sir, yes, sir!")

xxxxxxxxxx

example.py:1: too many nested for loops

Did you notice the caveat here? If the nested for loop is not a direct child of the parent loop, it is never visited, and hence not reported. However, getting our code to work on that edge case is nuanced, and is out of scope for this post.

Detecting Unused Imports

Detecting unused imports is different from the previous cases because we can’t flag the violations immediately while visiting nodes — we don’t have the complete information about what all ‘names’ are gonna be used in the entire module. Therefore, we implement this analyzer in two passes:

- In the first pass, we go through all the nodes where the imports may be defined (

ast.Import,ast.ImportFrom), collecting the names of all the modules which have been imported. - In the same pass, we also populate a set with all the names that are being used in that file by implementing a visitor for

ast.Name. - In the second pass, we see which names were imported, but not used. We then print an error message for all such names.

xxxxxxxxxx

class UnusedImportChecker(BaseChecker):

def __init__(self):

self.import_map = defaultdict(set)

self.name_map = defaultdict(set)

def _add_imports(self, node):

for import_name in node.names:

# Store only top-level module name ("os.path" -> "os").

# We can't easily detect when "os.path" is used.

name = import_name.name.partition(".")[0]

self.import_map[self.filename].add((name, node.lineno))

def visit_Import(self, node):

self._add_imports(node)

def visit_ImportFrom(self, node):

self._add_imports(node)

def visit_Name(self, node):

# We only add those nodes for which a value is being read from.

if isinstance(node.ctx, ast.Load):

self.name_map[self.filename].add(node.id)

def report(self):

for path, imports in self.import_map.items():

for name, line in imports:

if name not in self.name_map[path]:

print(f"{path}:{line}: unused import '{name}'")

- Whenever an

ImportorImportFromnode is encountered, we store its name in a set. - To get a set of all the names being used in a file, we visit

ast.Namenodes: for each such node, we check if a value is being read from it — which implies that a reference to an already existing name is being made, rather than creating a new object. (If it is an import name, it has to exist already) — if yes, we add the name to the set. - The

reportmethod traverses over the list of all the import names in a file and checks if they’re present in the set of used names. If not, it prints an error message reporting the violation.

Let’s go ahead and run this script on a few examples

xxxxxxxxxx

import antigravity

import os.path.join

import sys

import this

tmpdir = os.path.join(sys.path[0], 'tmp')

xxxxxxxxxx

example.py:1: unused import 'antigravity'

example.py:4: unused import 'this'

Please note that for the sake of brevity, I went with the simplest version of the code possible. This choice has a side effect that our code doesn’t handle some tricky corner cases (e.g., when imports are aliased - import foo as bar, or when the name is read from the locals() dict, etc.).

Phew! This was a whole list of things to wrap your head around with. But, our reward is that the next time we identify a pattern of bug-causing-code, we can go right ahead and write a script to automatically detect it.

References

Published at DZone with permission of Rahul Jha. See the original article here.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments