The Facade Pattern

Learn about the Facade pattern and how it simplifies interactions that clients need to make with subsystem classes.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeThe Facade pattern is a part of the classic Gang of Four structural pattern family. We already learned about the other patterns in the structural pattern family – Adapter, Bridge, Composite, and Decorator.

“Provide a unified interface to a set of interfaces in a subsystem. Facade defines a higher-level interface that makes the subsystem easier to use.”-- Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software

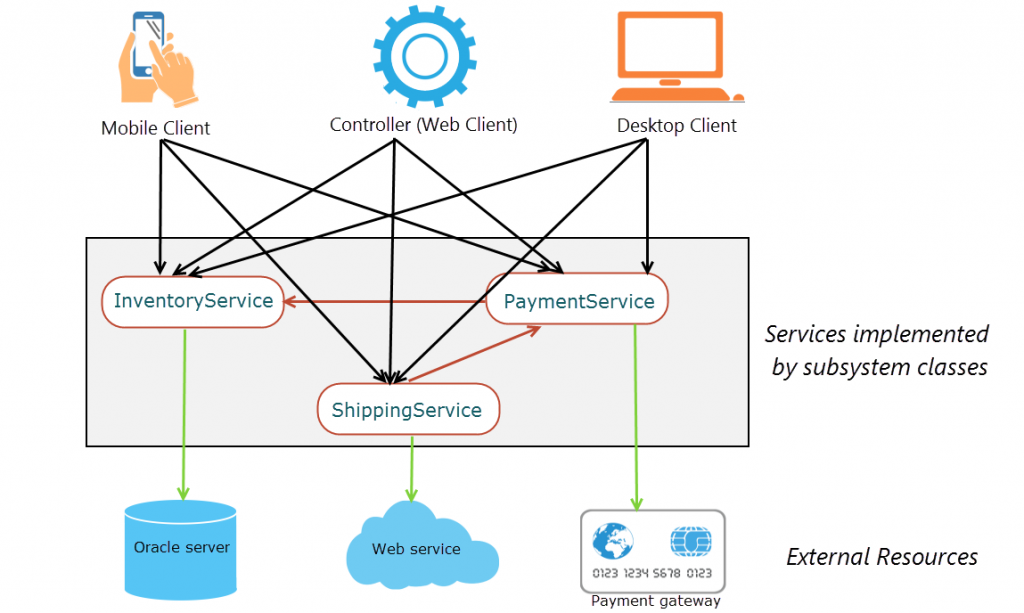

When we create a system, we divide it into subsystems to reduce complexities. We assign specific responsibilities to the subsystem classes by following the Single Responsibility Principle. But, often dependencies between the subsystems exist. In addition, clients individually interacting with the subsystem classes to fulfill a business requirement can result in a significant level of complexity.

Consider an order fulfillment process of an e-commerce store. When a user places an order for a product, the following services completes the process:

- Inventory service: Checks the warehouse database running on Oracle for the availability of the product.

- Payment service: Connects with a payment gateway to process the order payment.

- Shipping service: Connects with an external logistic web service to ship the product from the warehouse to the user’s address.

A controller of the application interacts with the preceding services for an order. When a user interacts with the UI to place an order, the request is mapped to the controller, which in turn interacts with the services to fulfill the request, and then informs the user about the fulfillment status. In a real e-commerce store application, the controller will typically be a specialized component of the underlying framework, such as a Spring MVCcontroller.

Our e-commerce store also supports mobile clients. Users can download the client app and place an order from their devices. Legacy desktop clients can also communicate with the store as continuing support for users who wants to place an order over the phone through a customer service assistant. This is how different clients interact with the order fulfillment process of the e-commerce store.

As you can see in the figure above, the clients need to make multiple interactions with the services implemented by subsystem classes, and to do so, the clients need to be aware of the internals of the subsystem classes. It means, our clients are tightly coupled with the subsystem classes – a fundamental violation of the SOLID design principles. Imagine the impact if the underlying data store needs to be changed to a NoSQL database or the current payment gateway is replaced with another one. Things can get more worse if a new InvoicingService is introduced in the service layer or the existing ShippingService is updated to make the logistic part internal to the organization. Due to this tight coupling, any changes in the service layers will propagate to the client layer. This makes changes time consuming and error prone.

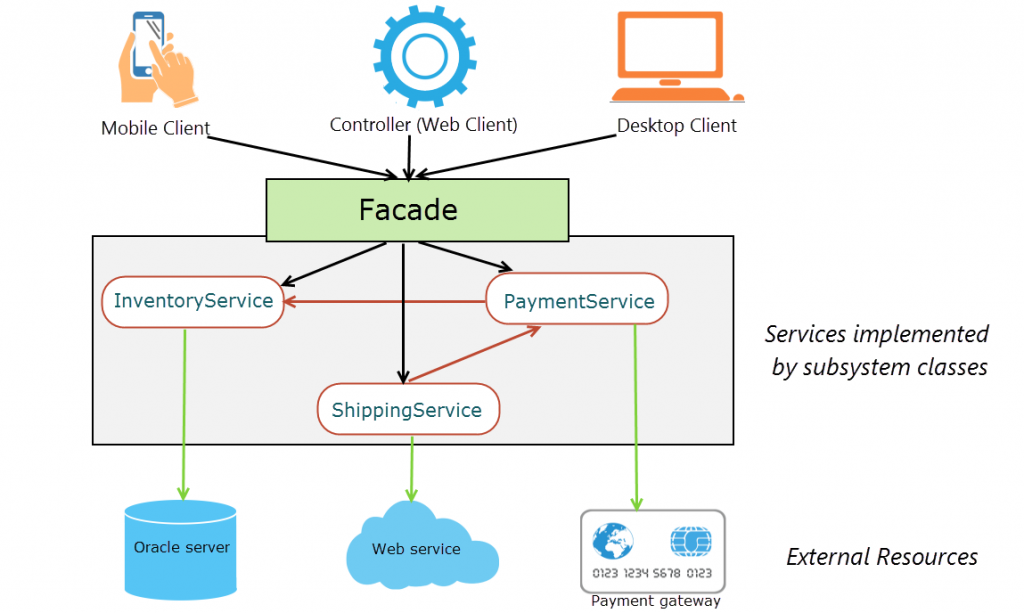

Rather than having the clients tightly coupled to the subsystems, we need is an interface which makes the subsystems easier to use. In our example, our clients just want to place an order. They don’t really need to care about dealing with inventory, shipping or payments. The Facade pattern is a way of providing a simple way for the clients to interact with the subsystems. By working through a facade, now we can make changes to the subsystem classes without affecting the client code. In short we make clients loosely coupled with the subsystem classes.

With a facade, this is how different clients interact with the order fulfillment process.

As you can see in the figure above, with the introduction of a facade, clients now interact with the facade for an order fulfillment instead of individual subsystem services. The facade handles the underlying interactions with the subsystem services transparently from the clients.

Accordingly, we can categorize the participants of the Facade pattern as:

- Facade: Delegates client requests to appropriate subsystem classes.

- Subsystem classes: Implements subsystem functionalities. Subsystem classes are used by the facade, but not the other way around. We will come to it later in this post.

- Client: Requests the facade to perform some action.

Applying the Facade Pattern

To apply the facade pattern to our order fulfillment example, let’s start with the domain class – Product.

Product.java

package guru.springframework.gof.facade.domain;

public class Product {

public int productId;

public String name;

public Product(){}

public Product(int productId, String name){

this.productId=productId;

this.name=name;

}

}I have kept the Product class simple with only two fields, a constructor to initialize them, and the default constructor.

We will next write the subsystem service classes.

InventoryService.java

package guru.springframework.gof.facade.subcomponents;

import guru.springframework.gof.facade.domain.Product;

public class InventoryService {

public static boolean isAvailable(Product product){

/*Check Warehouse database for product availability*/

return true;

}

}PaymentService.java

package guru.springframework.gof.facade.subcomponents;

public class PaymentService {

public static boolean makePayment(){

/*Connect with payment gateway for payment*/

return true;

}

}ShippingService.java

package guru.springframework.gof.facade.subcomponents;

import guru.springframework.gof.facade.domain.Product;

public class ShippingService {

public static void shipProduct(Product product){

/*Connect with external shipment service to ship product*/

}

}The subsystem classes represent different services for the order fulfillment process. One thing to note is that the subsystem classes have no reference to the facade. The classes are not aware of any Facade and are designed to work independently, even if a facade does not exist. Remember – Subsystem classes are used by the facade, but not the other way around.

For the purpose of the example, I kept the service classes to the bare minimum. This is only for illustrative purposes. A real e-commmerce example would be much more complex.

We can have a concrete facade class without any interface – the pattern does not mandates one. However, we will provide an interface to follow- “Depend upon abstractions. Do not depend upon concretions” which sums up Dependency Inversion principle. By doing so, we can have clients programmed against this interface to interact with the services through the facade. Writing our code to an interface also loosens the coupling between the classes.

OrderServiceFacade.java

package guru.springframework.gof.facade.servicefacade;

public interface OrderServiceFacade {

boolean placeOrder(int productId);

}We will implement the interface in the OrderServiceFacadeImpl class.

OrderServiceFacadeImpl.java

package guru.springframework.gof.facade.servicefacade;

import guru.springframework.gof.facade.domain.Product;

import guru.springframework.gof.facade.subcomponents.PaymentService;

import guru.springframework.gof.facade.subcomponents.ShippingService;

import guru.springframework.gof.facade.subcomponents.InventoryService;

public class OrderServiceFacadeImpl implements OrderServiceFacade{

public boolean placeOrder(int pId){

boolean orderFulfilled=false;

Product product=new Product();

product.productId=pId;

if(InventoryService.isAvailable(product))

{

System.out.println("Product with ID: "+ product.productId+" is available.");

boolean paymentConfirmed= PaymentService.makePayment();

if(paymentConfirmed){

System.out.println("Payment confirmed...");

ShippingService.shipProduct(product);

System.out.println("Product shipped...");

orderFulfilled=true;

}

}

return orderFulfilled;

}

}In the facade we implemented the placeOrder() method that consolidates all subsystem interactions. In this method, we called methods on the services to perform the operations of fulfilling an order.

Next we will write the controller class – the client of the facade.

OrderFulfillmentController.java

package guru.springframework.gof.facade.controller;

import guru.springframework.gof.facade.servicefacade.OrderServiceFacade;

public class OrderFulfillmentController {

OrderServiceFacade facade;

boolean orderFulfilled=false;

public void orderProduct(int productId) {

orderFulfilled=facade.placeOrder(productId);

System.out.println("OrderFulfillmentController: Order fulfillment completed. ");

}

}The OrderFulfillmentController client class we wrote is very simple as it should be. The client controller calls the placeOrder() method of the facade and stores the result in a boolean.

Far too often I see junior programmers clutter up controller classes. In a MVC design pattern, a controller has absolutely no business interacting with the database layer directly. It’s too common to see a JDBC datasource being used directly in a controller class. This is a clear violation of the Single Responsibility Principle. Controllers have a single purpose, and that is to respond to the web request. It is not to call on a database, it is not to use Hibernate, it is not to manage database transactions.

Because our controller has only one function in life, it’s easy to test.

OrderFulfillmentControllerTest.java

package guru.springframework.gof.facade.controller;

import guru.springframework.gof.facade.servicefacade.OrderServiceFacadeImpl;

import org.junit.Test;

import static org.junit.Assert.*;

public class OrderFulfillmentControllerTest {

@Test

public void testOrderProduct() throws Exception {

OrderFulfillmentController controller=new OrderFulfillmentController();

controller.facade=new OrderServiceFacadeImpl();

controller.orderProduct(9);

boolean result=controller.orderFulfilled;

assertTrue(result);

}

}The output of the test is this.

-------------------------------------------------------

T E S T S

-------------------------------------------------------

Running guru.springframework.gof.facade.controller.OrderFulfillmentControllerTest

Product with ID: 9 is available.

Payment confirmed...

Product shipped...

OrderFulfillmentController: Order fulfillment completed.

Tests run: 1, Failures: 0, Errors: 0, Skipped: 0, Time elapsed: 0.19 sec - in guru.springframework.gof.facade.controller.OrderFulfillmentControllerTestConclusion

Of the GoF patterns, I found the Facade pattern one of the simplest to understand and apply. Actually, before I knew about it, I was already applying it intuitively. Once you understand the Facade pattern, you will recognize it in use more and more.

It is common for programmers to confuse the Facade pattern with the Adapter pattern. Keep in mind is that Facade in general is about reducing the complexity of interfacing with a subsystem, whereas Adapter is more geared towards tweaking an existing interface to another interface that a client expects to work with.

In Enterprise Applications developed with Spring, a facade is commonly used to consolidate all the business services the application provides to its users. In Spring applications, you will be often developing business and service facades that serves as a gateway to business logic and the service layer of the application. For persistence, you will write DAOs, a type of facade, but specific to the data layer. While, I kept this example intentionally generic, you should be able to see how this would work nicely with Spring in the context of IoC and Dependency Injection.

Published at DZone with permission of John Thompson, DZone MVB. See the original article here.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments