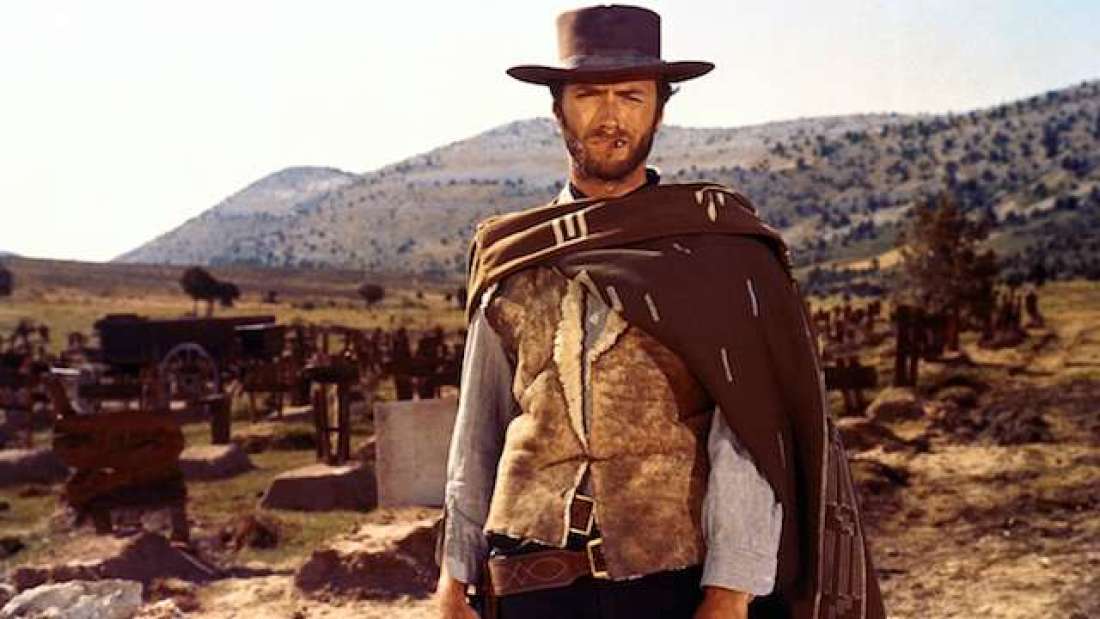

The Good, The Bad And The Ugly About Estimates

Estimates can be useful when they are considered as such, but managment should be mindful of a few rules when thinking about how to approach them.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For Free

Ask any developer to estimate how long it will take for them to finish a project. You will see the loathing in their eyes. And for good reason. Estimates have been wrongly used for decades by a lot of managers who then hold the team accountable to their estimate as if it were the actual deadline. Even more frustrating, in many cases, those managers only act on the lowest number they hear from you! It’s as if they had a min() function, and they just keep trying to get the number lower. But engineering is not magic!! No wonder the hashtag #NoEstimates has become famous.

For this to happen, we (well…especially managers) need to abide by a few rules. Then we’ll see how estimates can improve the quality of your software. Yup, you read that right. Well, in my opinion, obviously.

Don’t Mess with the Rules of Estimation!

Rule #1: Never ever consider an estimate as a commitment to a deadline.

Or, you risk losing your team’s trust at once, and it will be hard to get their trust back. The funny thing here is that even managers don’t know exactly what they will get done by the end of the day. So how can they imagine developers will know exactly what they will have accomplished, given their productivity can be randomly impacted and that most of the time projects have a lot of unknowns? Nothing is magic!

Rule #2: Don’t ever share your estimate outside of your team or to other related departments.

I guess that’s even worse than rule #1. Communicating an estimate carries the risk that it will automatically switch to a commitment to a deadline, and other departments will adjust their priorities accordingly, putting even more pressure on your team.

Rule #3: If you have a ballpark estimate, the reality is most likely in between the lower and higher boundaries, but not on the lower one.

As a manager, you cannot actually influence the delivery date by just wishing unless you change the scope or quality of the project. But otherwise, you cannot. If you are given a ballpark figure with a high and low estimate, you would be smarter to consider both pieces of information. Even the PMP introduced the term PERT (Program Evaluation and Review Technique) to get closer to what the end result will be.

Rule #4: The uncertainty of estimates is linked to the unknowns. The more unknowns, the less confident you should feel about the estimate.

But also the fewer unknowns, the more confident you should feel about the estimates.

What does this mean? Every project has a certain level of unknowns attached to it. When developers give you a ballpark estimate, let’s say 4-8 days, they give you 2 valuable pieces of information: the number of days and how confident they feel about it. Another way to view it is like this: 6 days with 2 days of uncertainty (or 33% uncertainty). If the uncertainty is important, it means that there are potentially many unknowns that could impact the eventual delivery. These unknowns can have a lot of impact, or none at all. My point here is that the chances are greater for estimates to go awry (even outside of the defined boundaries) when the uncertainty is high.

Rule #5: Addressing unknowns first does increase the confidence on estimates.

There are 2 types of unknowns: unknown unknowns and known unknowns. There is not much you can do for unknown unknowns. And by definition, developers can’t really take them into consideration in their estimates; they might have given themselves a few more days just in case, and those days are usually actually spent on debugging. However, concerning known unknowns, spending the first hours or days of your project to address them can significantly alleviate doubts on the work to be done in the end. This way you can reduce the uncertainty mentioned in rule #4. For instance, the 6 days +/- 2 days, can become 6 days +/- 1 day.

By the way, you can understand that specs are part of the possible known unknowns. The more precise the specs are, the fewer uncertainties there will be. So get to work, PMs.

Rule #6: If an estimate seems fine to you (and you’re the high-expectation kind of manager), you may want to ask the right questions.

If a developer tells you it’s going to take 4 days for a project, and you were expecting 5, and you always have a tendency to be too optimistic, then it may mean the developer doesn’t have the same thing in mind for the task as you do. I would personally advise you to ask yourself some of the following questions:

- Are the specs well understood?

- Can the technology or architecture scale to the number of users we want?

- Can it last at least 24 months?

- What are the risks associated with this solution and to the choices about to be made?

The point is, you might not be thinking about the same level of requirements for the solution. Again, there is no magic.

Rule #7: If you ever need a deadline, respect the cone of uncertainty.

Sometimes you need to have a release date defined a few weeks/months early because you are not the only ones that need to meet the deadline for that particular project. This is a reality that you need to consider. In this case, have you heard about the cone of uncertainty?

The graph is pretty self-explanatory, but in a few words: you can’t ask for promises too early on. Promises don’t work well with unknowns. So the first thing to do is to set the release date for as late as possible. But if you really have to give a timeline early on, ask your team to be exploratory at first and try to address all unknowns before starting to agree on a date. Keep in mind, though, that your team should be defining or influencing the date as much as possible. If not, you take the chance of impacting the scope or quality of your project.

Rule #8: Analysis paralysis is easily surmountable.

Okay…so this is not a rule per se. But it’s a good hack for managers. Developers might not really appreciate it at first, but I think it does initiate the conversation, and if in the end, you agree that estimates can have value for developers, then maybe developers will be ok with this rule.

If a developer doesn’t want to give you an estimate because the task is too complicated (and to be fair, estimating is no easy task), an easy way to initiate the discussion is to just throw out a very high number like “100 days.” The developer will probably say, “Hell, no!” Then you work your way down with lower and lower numbers until the developer tells you, “Maybe.” Then do the same, but with a very low number; the developer will again tell you, “Impossible!” And again you work your way up until the developer tells you, “Possibly.” There! You have a ballpark estimate to start with. But don’t forget to respect all the other rules — an estimate is not a committed delivery time.

Okay, so we’ve gone through the rules. Don’t hesitate to add more in the comments. I will edit the article with your input. Now, let’s suppose our team respects all the rules as to how and why estimates can be useful to developers.

Why Would Developers Be More than Okay with Estimates?

If you don’t need to have a predefined release date, you might wonder why you would even need estimates at all. Valid question, my friend.

In my mind, the point of estimates is that they create discussions and mutual understanding around the unknowns. When you discuss estimates, if any of them are a bit off, it will create discussions, and the developer could go to the whiteboard to sketch their understanding of the work to be done for the tasks at hand. If their understanding is a bit off, other developers might clarify some point in the architecture of the code. You might even have cases where a senior developer can learn some great hacks from more junior ones.

Estimates create discussions that educate developers on the code and its architecture. They can eventually uplevel the quality of the code itself and even help developers tackle tasks faster than they would have done otherwise. However, note that to take the most advantage of estimates, they should be done as a team. You could also reflect on the estimates during your post mortems; there will be more lessons to be learned.

In the end, the benefits gained are a trade-off with the time spent by the team on the estimates. There are many ways to do this. For instance, estimates could have their own dedicated meetings that should be kept focused as much as possible. We all know about meetings…enough said.

Just a last note. If you have second thoughts on estimates you’ve been given, you might also consider "gamifying" the process to engage your developers. For example, score the team’s accuracy across weeks or projects and have some kind of congratulatory gifts when beating a new record. Well, just an idea. Let me know if I missed any rules, or if you don’t agree with my conclusions.

Before You Go…

Learned something? Don’t hesitate to share it to help others find it!

If you are interested in articles about engineering leadership, productivity and how to scale a team, check out our blog at Anaxi.

You can also follow me on Twitter to stay connected. Thank you!

Published at DZone with permission of John Lafleur. See the original article here.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments