What Is Refactoring?

Refactoring is a fundamental skill for developers, so let's dive into some standard techniques and how to apply them to reduce technical debt.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeRefactoring is one of the most used terms in software development and has played a major role in the maintenance of software for decades. While most developers have an intuitive understanding of the refactoring process, many of us lack a true mastery of this important skill. In this article, we will explore the textbook definition of refactoring, how this definition holds up to the reality of software development, and how we can ensure our codebase is prepared for refactoring. Along the way, we will walk-through an entire set of refactorings, from start to finish, to illustrate the simplicity and importance of this ubiquitous process.

A Simple Definition

Refactoring is one of the most self-evident processes in software development, but it is surprisingly difficult to perform properly. In most cases, we deviate from strict refactoring and execute an approximation of the process; sometimes, things work out and we are left with cleaner code, but other times, we get snared, wondering where we went wrong. In either case, it is important to fully understand the importance and simplicity of barebones refactoring. Martin Fowler, the author of the seminal work on the topic, defines refactoring as follows:

Refactoring is a controlled technique for improving the design of an existing code base. Its essence is applying a series of small behavior-preserving transformations, each of which "too small to be worth doing". However the cumulative effect of each of these transformations is quite significant. By doing them in small steps you reduce the risk of introducing errors. You also avoid having the system broken while you are carrying out the restructuring — which allows you to gradually refactor a system over an extended period of time.

In short, the process of refactoring involves taking small, manageable steps that incrementally increase the cleanliness of code while still maintaining the functionality of the code. As we perform more and more of these small changes, we start to transform messy code into simpler, easier to read, and more maintainable code. It is not a single refactoring that makes the change: It's the cumulative effect of many small refactorings performed toward a single goal that makes the difference.

For example, if we want to simplify a method, renaming a single variable may make little difference for a large method body, but if by renaming this variable we find that another variable represents the same value, we can remove the duplicate variable. That removes one line from the method, which may seem insignificant, but as we continue the process, more and more lines are removed and the method body starts to shrink. In some cases, the method may shrink to such a trivial level that we replace calls to the method with the method body itself (termed inlining).

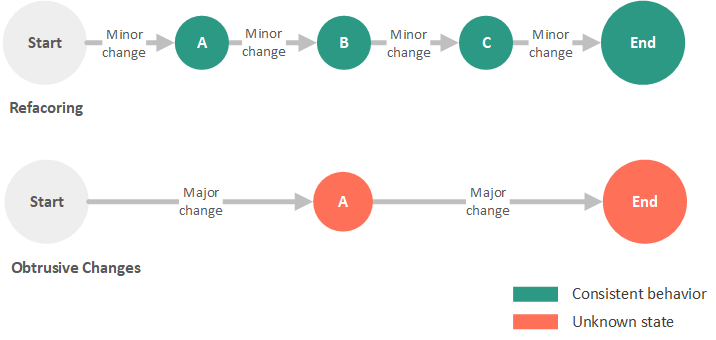

As we remove the method, we may realize that the class that contained the method may be so small, it is no longer worth it to have its logic in a separate class. We then move the remaining methods to a more appropriate class and remove the original class. By simply changing variable names and reducing duplication, the refactoring process snowballed into the removal of a method and eventually a class. It is important to note that throughout this process, we never changed the externally visible behavior of the application: We simply shifted around logic and removed duplication, but the application continued to function as it did before we started the refactoring process. This process is visually contrasted in the figure below with that of obtrusive changes that make major alterations to code in a single, sweeping motion.

Standard Refactoring Techniques

In this sense, refactoring is analogous to rock climbing. We start on the ground and find a solid place to grab hold of. Next, we step up and check our footing. Then we find a new place to grab, moving our hands and our feet to position ourselves higher up the rock face. At each step, we test our footing before moving to the next position. While every few feet we progress may seem insignificant in comparison to the hundreds of feet of the rock face, each step puts us a few feet higher than the previous step. After some time, we look down and see that we have traveled quite a distance up the rock face.

Just as with rock climbing, there are a standard set of techniques that can be used to safely and effectively accomplish the task at hand. In refactoring, these procedures are called refactoring techniques and there is a standard catalog of these techniques currently published. Each of these techniques is known to perform a safe transformation of code, where the behavior of the system is unchanged but the readability or the simplicity of the code is improved. A comprehensive listing of these techniques, including some very useful information, can be found in Martin Fowler's Refactoring. These refactoring techniques have also been collected into an interactive website called Refactoring Guru. It is highly suggested that the reader familiarize him or herself with these techniques, as they constitute the vocabulary of refactoring. For example, it is common to hear a developer state that he or she will "inline" a method or "pull up" a method or field in a hierarchy.

Making Progress

It is important to understand that refactoring is not a Sisyphean effort: There is a light at the end of the tunnel. Although removing one line in a code base of thousands, hundreds of thousands or even millions of lines of code may seem futile, it is not. Just as the system was built one line at a time, it can be cleaned up one line, one variable, one method, and one class at a time. It may seem futile since it appears that refactoring is truly never finished, but unlike Sisyphus, we are not doomed from the start and we are not cursed to never make progress. It requires a decent degree of patience, as well as a few important prerequisites.

Prerequisites

Not every code base can be refactored. Although any code can be cleaned up, only a specific code base can be truly refactored. In order to perform this process, we must have two prerequisites in place: (1) a goal and (2) quick, automated tests.

A Goal

When refactoring, we need to have a goal in mind. This goal does not need to be complex or even large, but we need to have criteria to know when we have sufficiently refactored our code. For example, we may have a very complex class hierarchy, with unneeded levels of interfaces, abstract classes, and concrete implementations. Our goal for this hierarchy can be to reduce the number of classes to some manageable number. We can accomplish this by moving methods up and down the hierarchy, composing classes rather than inheriting them, and a host of other generalization techniques.

Some tips to keep in mind when establishing a goal include:

- Keep it simple: Start small and maintain focus on a reasonably-sized goal

- Break down large goals: If a goal involves refactoring hundreds of classes at once, break down this goal into small pieces; pick a smaller subset of classes to refactor; once the refactor is completed on this subset, move onto another subset

- Be specific: Do not fall into the trap of stating that a goal is to "tidy up a method" or "clean up a class" (vague and abstract goals); instead, set a more measurable goal, such as to remove nested loops, remove complicated conditionals, reduce the number of lines of a method by moving common code into a private method, etc.

- Focus on the end: Do not get distracted by the intermediate steps that are required to reach a goal; if reducing an inheritance hierarchy requires the creation of a few classes and the removal of others, do not get bogged down and forget that the end goal is to refactor the hierarchy, not simply add and remove classes

Although there is always more to refactor in a code base, start small and make progress. Completing a small refactoring earns us a level of confidence and satisfaction. With a goal in mind, we can now provide the technical requirement for refactoring: Quick and automated tests.

Automated Tests

Two of the most important questions we can ask ourselves when we work through the refactoring process are:

- What is the desired behavior of the system?

- How do we know that it will remain consistent when we make a change?

Both of these questions can be answered with tests. In theory, each time we make a small change to the system, the only way we can know what the intended behavior of the system is and know that we did not change it is to run a suite of tests for the code. In pragmatic terms, we need this test suite execute quickly and provide us with a simple yes or no answer to the question: Does everything still behave as intended? In real-world applications, this means swift, automated tests that fully exercise the behavior of the system. In summary, our tests must have the following characteristics in order for us to refactor code:

- Execute quickly

- Provide full coverage

- Pass if the correct behavior of the system is exhibited and fail otherwise

Full coverage is difficult to strictly define, but it includes all of the unit, integration, acceptance, performance, and stress tests that accompany an application or the section of the application we are concerned with refactoring. It is important that these tests be quick to run since we must get feedback relatively quickly in order for our refactoring to be fruitful. If tests take a long time to run, it is unlikely that we will run them each time we make a change. For example, if we are performing small refactorings that each takes about 15 seconds to complete and the test suite takes 10 minutes to run, it is very unlikely that we will run the entire test suite after each refactoring. Note that not every test in the application needs to be run (e.g. long-running acceptance tests for an unrelated part of the system), but a sufficient degree of them should be run to ensure that we have not changed the behavior of the system when we refactored.

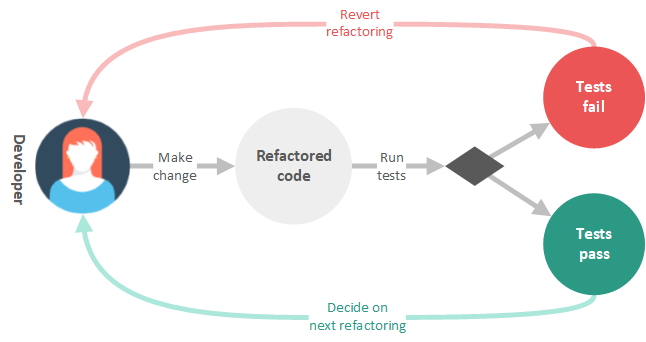

These tests allow us to know that any change we make does not alter the behavior of the system. By using these tests, we can systematically perform a cycle of refactoring without worrying that we will break the system. This cycle starts with us making a change, running the tests, and seeing if the tests pass. If they do, we can rest assured that our refactor did not adversely affect the system, and continue with another refactoring. If the tests fail, we know that we have altered the system in some externally noticeable way and should undo our changes (which in actuality, was not a refactoring since it changed the external behavior of the system). This process is illustrated in the figure below.

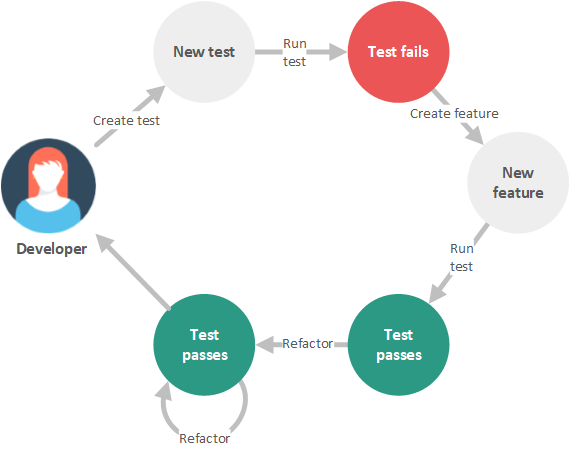

This is very similar to the Test Driven Design (TDD) cycle, which actually includes a refactoring step. In TDD, we create a new test case, watch it fail, create a new feature, and ensure that the new feature passes our test case. Once the feature passes the test case, we can perform refactoring on the new feature. Each time we refactor the feature, we rerun all of the tests to ensure that we have not inadvertently altered the behavior of the feature. Once we are finished with our feature, we repeat the cycle, adding new tests and other features to the system. This process is illustrated in the figure below.

While it takes good judgment to know when and where to refactor, the process of refactoring is systematic: Make a change and test. This cycle should not be broken, as making an untested change can cause serious problems down the road. For example, suppose we perform five refactorings and then test. If the tests fail, we do not know which of the refactorings altered the behavior of the code and it may be difficult to undo each of these refactorings individually. Therefore, it is important to be deliberate in our refactoring process and not to outrun our headlights. In short, we should follow the old military adage:

Slow is smooth, smooth is fast

Before we move onto an example, it is important that we take a minute to understand what elicits the need to refactor in the first place, where to look for code that needs refactoring, and what we should recognize as code in need of refactoring.

Accumulating Mess

In a perfect world, our first pass at creating code would result in flawless, readable code that requires no changes. Each time we add to existing code, we would likewise take the time to clean it up so that the new code melds with the existing code as if the two were originally designed for one another. In reality, we do not live in a perfect world: We have project budgets, time constraints, personal lives, cars that break down, sick days that get taken, and corners that get cut.

So how do we end up in a place where we are in need of refactoring? Each time we write code or make changes to existing code, we accrue technical debt (for more information, see the Refactoring Guru article on the topic). We (understandably) take reward now for pain later. Instead of taking the time to write clean code, we get the job done and move onto the next task. We do not have the time to stop and make sure that our methods are clean or take time to reflect and see if we could have simplified our inheritance hierarchy. When a deadline is bearing down on us, families at home that require our attention, and a host of other tasks to complete, something has to give. This is the time when we say, "I know it's not the way I want it to look, but it works. I'll come back to this later when I have some free time." But we know, just as Benjamin Franklin said:

Tomorrow, every Fault is to be amended; but that Tomorrow never comes.

Instead, we take out a loan: Writing messy code that works now for the promise of cleaning it up later. Just like with monetary debt, though, this postponement accrues interest: Cleaning up the code later will be much more difficult than it is right now. While it may be more difficult, we are not out of luck. There is a way to make repayments and reduce the principal on this loan: Refactoring. Even if we stumble across messy code (whether written by ourselves or others), it does not mean that it has to remain messy. In fact, a few simple changes can go a long way in improving the readability and simplicity of code and even reduce the hassle of future tasks (it is much easier to add a feature to clean code than it is to messy code).

As we will see in the following section, we can take messy code and improve it without breaking it. This is not some pie-in-the-sky goal that is intended for impractical settings, but rather, can be accomplished in a relatively short period of time (relative to the gain we obtain), so long as we are diligent in following the refactoring process.

Refactoring in Action

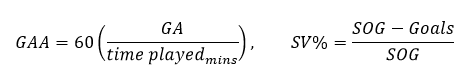

Arguably, the most effective way to understand refactoring is to see it in action. To do this, we will create an application that is responsible for calculating the statistics for a goalie over a single ice hockey season. The two statistics we are interested in are

- Goals Against Average (GAA): The number of goals scored against a goalie (called Goals Against, GA) divided by the number of minutes the goalie played for a season multiplied by 60 (the number of minutes per hockey game)

- Save Percentage (SV%): The total number of saves (Shots on Goal, SOG, minus the number of goals scored on a goalie) divided by the total SOG.

Stated formally:

To calculate these values, we create the following classes (note that the test cases for these classes can be found in this GitHub repository):

public class Game {

private final double minutesPlayed;

private final int goalsAgainst;

private final int shotsOnGoalAgainst;

public Game(int goalsAgainst, int shotsOnGoalAgainst, double minutesPlayed) {

this.goalsAgainst = goalsAgainst;

this.shotsOnGoalAgainst = shotsOnGoalAgainst;

this.minutesPlayed = minutesPlayed;

}

public int getGoalsAgainst() {

return goalsAgainst;

}

public int getShotsOnGoalAgainst() {

return shotsOnGoalAgainst;

}

public double getMinutesPlayed() {

return minutesPlayed;

}

}

public class Season {

private final List<Game> games;

public Season(List<Game> games) {

this.games = new ArrayList<>(games);

}

public Season() {

this.games = new ArrayList<>();

}

public void addGame(Game game) {

games.add(game);

}

public void removeGame(Game game) {

games.remove(game);

}

public List<Game> getGames() {

return games;

}

public GoalieStatistics getGoalieStatistics() {

return new GoalieStatistics(this);

}

}

public class GoalieStatistics {

private final Season season;

public GoalieStatistics(Season season) {

this.season = season;

}

public double getGoalsAgainstAverage() {

if (season.getGames().isEmpty()) {

return 0.0;

}

else {

List<Game> games = season.getGames();

int tga = 0;

double mins = 0;

for (Game game: games) {

tga += game.getGoalsAgainst();

mins += game.getMinutesPlayed();

}

return (tga / mins) * 60;

}

}

public double getSavePercentage() {

if (season.getGames().isEmpty()) {

return 0.0;

}

else {

List<Game> games = season.getGames();

int g = 0;

int tsoga = 0;

for (Game game: games) {

g += game.getGoalsAgainst();

tsoga += game.getShotsOnGoalAgainst();

}

return ((double) tsoga - g) / tsoga;

}

}

}While this code seems simple enough, there are a number of improvements that we can make. In particular, the methods in GoalieStatistics class can be simplified by removing the loops and improving the naming of the variables (our goal). At the moment, we can surmise what these methods are trying to accomplished, but we cannot read the methods clearly. First, we will split up the loops in both methods:

public double getGoalsAgainstAverage() {

if (season.getGames().isEmpty()) {

return 0.0;

}

else {

List<Game> games = season.getGames();

int tga = 0;

for (Game game: games) {

tga += game.getGoalsAgainst();

}

double mins = 0;

for (Game game: games) {

mins += game.getMinutesPlayed();

}

return (tga / mins) * 60;

}

}

public double getSavePercentage() {

if (season.getGames().isEmpty()) {

return 0.0;

}

else {

List<Game> games = season.getGames();

int g = 0;

for (Game game: games) {

g += game.getGoalsAgainst();

}

int tsoga = 0;

for (Game game: games) {

tsoga += game.getShotsOnGoalAgainst();

}

return ((double) tsoga - g) / tsoga;

}

}After this change, we rerun our tests and all of the tests still pass. This may seem counterintuitive: Why would we create more lines of code to accomplish our goal? If we look closely, we now see that both methods have the same logic for calculating the total SOG. To remove this duplication, we can use the extract method refactoring to pull this common logic out into a single method:

public double getGoalsAgainstAverage() {

if (season.getGames().isEmpty()) {

return 0.0;

}

else {

List<Game> games = season.getGames();

int tga = getTotalGoalsAgainst(games);

double mins = 0;

for (Game game: games) {

mins += game.getMinutesPlayed();

}

return (tga / mins) * 60;

}

}

private int getTotalGoalsAgainst(List<Game> games) {

int g = 0;

for (Game game: games) {

g += game.getGoalsAgainst();

}

return g;

}

public double getSavePercentage() {

if (season.getGames().isEmpty()) {

return 0.0;

}

else {

List<Game> games = season.getGames();

int g = getTotalGoalsAgainst(games);

int tsoga = 0;

for (Game game: games) {

tsoga += game.getShotsOnGoalAgainst();

}

return ((double) tsoga - g) / tsoga;

}

}We again run our tests and all our tests pass. With this loop extracted into its own method, we can now see we can simplify it into a single line using the Streams API:

private int getTotalGoalsAgainst(List<Game> games) {

return games.stream().mapToInt(game -> game.getGoalsAgainst()).sum();

}Again, we run all our tests and they all pass (for the remainder of this article, we will skip mentioning that we rerun tests after each step, but be sure to rerun them after each step, regardless of how small). If we look at this method, it has only one parameter: A list of Game objects obtained from the Season object. This should hint that this method probably belongs in the the Season class. In order to simplify our code, we will perform a move method refactoring, adding a public version of this method to the Season class, removing the single parameter, and removing the original private method in the GoalieStatistics class. Note that we also must change the calls to the original method to calls to the Season class version of the method. This results in the following definitions for the Season and GoalieStatistics classes:

public class Season {

private final List<Game> games;

// ...

public int getTotalGoalsAgainst() {

return games.stream().mapToInt(game -> game.getGoalsAgainst()).sum();

}

}

public class GoalieStatistics {

private final Season season;

public GoalieStatistics(Season season) {

this.season = season;

}

public double getGoalsAgainstAverage() {

if (season.getGames().isEmpty()) {

return 0.0;

}

else {

List<Game> games = season.getGames();

int tga = season.getTotalGoalsAgainst(games);

double mins = 0;

for (Game game: games) {

mins += game.getMinutesPlayed();

}

return (tga / mins) * 60;

}

}

public double getSavePercentage() {

if (season.getGames().isEmpty()) {

return 0.0;

}

else {

List<Game> games = season.getGames();

int g = season.getTotalGoalsAgainst(games);

int tsoga = 0;

for (Game game: games) {

tsoga += game.getShotsOnGoalAgainst();

}

return ((double) tsoga - g) / tsoga;

}

}

}We can repeat this process for the remaining loops in each of the GoalieStatistics methods. Note that we perform the extract method refactoring, followed by the method simplification (using the Streams API), followed by the move method refactoring, ensuring that all our tests pass after each step, not just at the beginning and the end of the three changes:

public class Season {

private final List<Game> games;

// ...

public int getTotalGoalsAgainst() {

return games.stream().mapToInt(game -> game.getGoalsAgainst()).sum();

}

public int getTotalShotsOnGoalAgainst() {

return games.stream().mapToInt(game -> game.getShotsOnGoalAgainst()).sum();

}

public double getTotalMinutesPlayed() {

return games.stream().mapToDouble(game -> game.getMinutesPlayed()).sum();

}

}

public class GoalieStatistics {

private final Season season;

public GoalieStatistics(Season season) {

this.season = season;

}

public double getGoalsAgainstAverage() {

if (season.getGames().isEmpty()) {

return 0.0;

}

else {

List<Game> games = season.getGames();

int tga = season.getTotalGoalsAgainst();

double mins = season.getTotalMinutesPlayed();

return (tga / mins) * 60;

}

}

public double getSavePercentage() {

if (season.getGames().isEmpty()) {

return 0.0;

}

else {

List<Game> games = season.getGames();

int g = season.getTotalGoalsAgainst();

int tsoga = season.getTotalShotsOnGoalAgainst();

return ((double) tsoga - g) / tsoga;

}

}

}If we look at our GoalieStatistics methods, we see that the games variable is now unused, so we can remove it. We can also rename the remaining variables in each of the methods to better describe the values they hold:

public class GoalieStatistics {

private final Season season;

public GoalieStatistics(Season season) {

this.season = season;

}

public double getGoalsAgainstAverage() {

if (season.getGames().isEmpty()) {

return 0.0;

}

else {

int totalGoalsAgainst = season.getTotalGoalsAgainst();

double totalMinutesPlayed = season.getTotalMinutesPlayed();

return (totalGoalsAgainst / totalMinutesPlayed) * 60;

}

}

public double getSavePercentage() {

if (season.getGames().isEmpty()) {

return 0.0;

}

else {

int totalGoalsAgainst = season.getTotalGoalsAgainst();

int totalSogAgainst = season.getTotalShotsOnGoalAgainst();

return ((double) totalSogAgainst - totalGoalsAgainst) / totalSogAgainst;

}

}

}There is one more refactoring that we can address: The call season.getGames().isEmpty() is simply checking if there are games played for a season. In other words, "has the season started yet?" In order to better convey the intent of this conditional check, we will extract this check into a method and move the method to the Season class:

public class Season {

private final List<Game> games;

// ...

public boolean hasStarted() {

return !games.isEmpty();

}

}

public class GoalieStatistics {

private final Season season;

public GoalieStatistics(Season season) {

this.season = season;

}

public double getGoalsAgainstAverage() {

if (!season.hasStarted()) {

return 0.0;

}

else {

int totalGoalsAgainst = season.getTotalGoalsAgainst();

double totalMinutesPlayed = season.getTotalMinutesPlayed();

return (totalGoalsAgainst / totalMinutesPlayed) * 60;

}

}

public double getSavePercentage() {

if (!season.hasStarted()) {

return 0.0;

}

else {

int totalGoalsAgainst = season.getTotalGoalsAgainst();

int totalSogAgainst = season.getTotalShotsOnGoalAgainst();

return ((double) totalSogAgainst - totalGoalsAgainst) / totalSogAgainst;

}

}

}Note that we have used the negative of the original call. We can accomplish this refactoring by extracting the original season.getGames().isEmpty() call into a method named hasNotStarted. We then run our tests and ensure our tests pass. We then negate the return value and negate the locations that the hasNotStarted method is called. We rerun our tests and then rename the hasNotStarted method to hasStarted (to match the functionality of the newly negated return value). We then retest, move the method to the Season class, and retest again. In order to remove the confusion of the negated if-statement, we can swap the conditionals in the if-statement:

public class GoalieStatistics {

private final Season season;

public GoalieStatistics(Season season) {

this.season = season;

}

public double getGoalsAgainstAverage() {

if (season.hasStarted()) {

int totalGoalsAgainst = season.getTotalGoalsAgainst();

double totalMinutesPlayed = season.getTotalMinutesPlayed();

return (totalGoalsAgainst / totalMinutesPlayed) * 60;

}

else {

return 0.0;

}

}

public double getSavePercentage() {

if (season.hasStarted()) {

int totalGoalsAgainst = season.getTotalGoalsAgainst();

int totalSogAgainst = season.getTotalShotsOnGoalAgainst();

return ((double) totalSogAgainst - totalGoalsAgainst) / totalSogAgainst;

}

else {

return 0.0;

}

}

}While we have reached a point where our GoalieStatistics class is sufficiently simplified, if we look closely, the getGames() method of the Season class is no longer called. If we wished, we could make this method private or completely remove it. If the determination was made that this method was no longer needed (and not used in other locations in the system), removing it would greatly increase the encapsulation and cohesion of the Season class. This is just one example of how refactoring one class may result in simplifications in improvements in others.

Note that the final code (after all refactorings above have been completed) can be found in this GitHub repository. Remember: This is only one way to refactor the GoalieStatistics class. Performing other refactorings may have led to another final set of classes. If we have done so, regardless of the specific sequence of refactorings we used, we have accomplished our mission.

Conclusion

Refactoring is one of the most fundamental skills that any developer can possess. Although it is often referred to in an informal manner, refactoring is a well-disciplined process requiring a goal, effective tests, and knowledge of the popular refactoring techniques. As we have seen in this article, no matter the state in which we find our code or the condition in which we left it, refactoring is an essential tool in paying down the principal on technical debt.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments