PowerShell parses text in one of two modes"command mode, where quotes are not required around a string and expression mode where strings must be quoted. The parsing mode is determined by what"s at the beginning of the statement. If it"s a command, then the statement is parsed in command mode. If it"s not a command then the statement is parsed in expression mode as shown:

Commands: There are 4 categories of commands in PowerShell:

| Cmdlets |

These are built-in commands in the shell, written in a .NET language like C# or Visual Basic. Users can extend the set of cmdlets by writing and loading PowerShell snap-ins. |

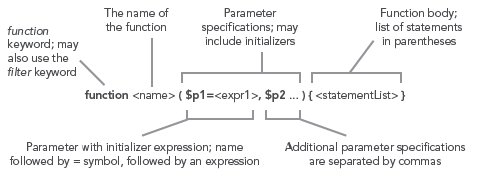

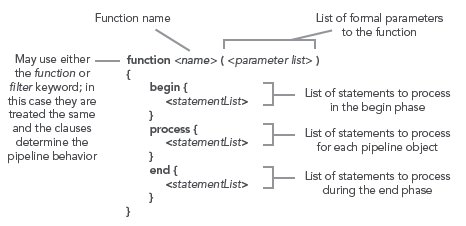

| Functions |

Functions are commands written in the PowerShell language that are defined dynamically. |

| Scripts |

Scripts are textfiles on disk with a .ps1 extension containing a collection of PowerShell commands. |

| Applications |

Applications (also canned native commands) are existing windows programs. These commands may be executables, documents for with there are associated editors like a word file or they may be script files in other languages that have interpreters registered and that have their extensions in the PATHTEXT environment variable. |

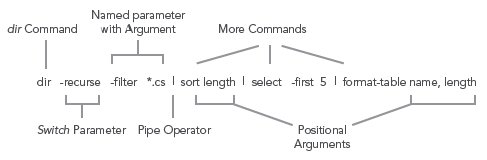

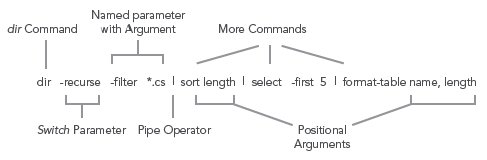

Pipelines: As with any shell, pipelines are central to the operation of PowerShell. However, instead of returning strings from external processes, PowerShell pipelines are composed of collections of commands. These commands process pipeline objects one at a time, passing each object from pipeline element to pipeline element. Elements can be processed based on properties like Name and Length instead of having to extract substrings from the objects.

PowerShell Literals: PowerShell has the usual set of literal values found in dynamic languages: strings, numbers, arrays and hashtables.

Numbers: PowerShell supports all of the signed .NET number formats. Hex numbers are entered as they are in C and C# with a leading "0x" as in 0xF80e. Floating point includes Single and Double precisions and Decimal. Banker"s rounding is used when rounding values. Expressions are widened as needed. A unique feature in PowerShell are the multiplyer suffixes which make it convenient to enter larger values easily:

| Multiplier Suffix |

Multiplication Factor |

Example |

Equivalent Value |

.NET Type |

| kb or KB |

1024 |

1KB |

1024 |

System.Int32 |

| mb or MB |

1024*1024 |

2.2mb |

2306867.2 |

System.Double |

| gb or GB |

1024*1024*1024 |

1Gb |

1073741824 |

System.Int32 |

Strings: PowerShell uses .NET strings. Single and Double quoted strings are supported. Variable substitution and escape sequence processing is done in double-quoted strings but not in single quoted ones as shown:

The escape character is backtick instead of backslash so that file paths can be written with either forward slash or backslash.

Variables: In PowerShell, variables are organized into namespaces. Variables are identified in a script by prefixing their names with a "$" sign as in "$x = 3". Variable names can be unqualified like $a or they can be name-space qualified like: $variable:a or $env:path. In the latter case, $env:path is the environment variable path. PowerShell allows you to access functions through the function names space: $function:prompt and command aliases through the alias namespace alias:dir

Arrays: Arrays are constructed using the comma "," operator. Unless otherwise specified, arrays are of type Object[]. Indexing is done with square brackets. The "+" operator will concatenate two arrays.

Because PowerShell is a dynamic language, sometimes you don"t know if a command will return an array or a scalar. PowerShell solves this problem with the @( ) notation. An expression evaluated this way will always be an array. If the expression is already an array, it will simple be returned. If it wasn"t an array, a new single-element array will be constructed to hold this value.

HashTables: The PowerShell hashtable literal produces an instance of the .NET type System.Collections.Hashtable. The hashtable keys may be unquoted strings or expressions; individual key/value pairs are separated by either newlines or semicolons as shown:

Type Conversions: For the most part, traditional shells only deal with strings. Individual tools would have to interpret (parse) these strings themselves. In PowerShell, we have a much richer set of objects to work with. However, we still wanted to preserve the ease of use that strings provide. We do this through the PowerShell type conversion subsystem. This facility will automatically convert object types on demand in a transparent way. The type converter is careful to try and not lose information when doing a conversion. It will also only do one conversion step at a time. The user may also specify explicit conversions and, in fact, compose those conversions. Conversions are typically applied to values but they may also be attached to variables in which case anything assigned to that variable will be automatically be converted.

Here"s is an example where a set of type constraints are applied to a variable. We want anything assigned to this variable to first be converted into a string, then into an array of characters and finally into the code points associated with those characters.

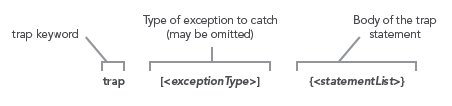

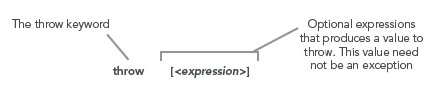

Flow-control Statements: PowerShell has the usual collection of looping and branching statements. One interesting difference is that in many places, a pipeline can be used instead of a simple expression.

if Statement:

The condition part of an if statement may also be a pipeline.

while Loop:

for Loop:

foreach Loop:

foreach Cmdlet: This cmdlet can be used to iterate over collections of operators (similar to the map() operation found in many other languages like Perl.) There is a short alias for this command "%". Note that the $_ variable is used to access the current pipeline object in the foreach and where cmdlets.

where Cmdlet: This cmdlet selects a subset of objects from a stream based on the evaluation of a condition. The short alias for this command is "?".

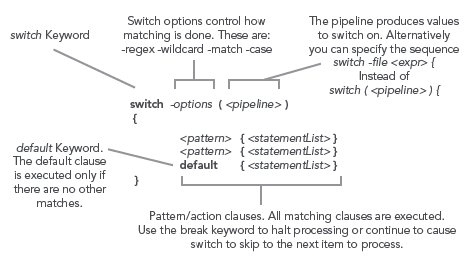

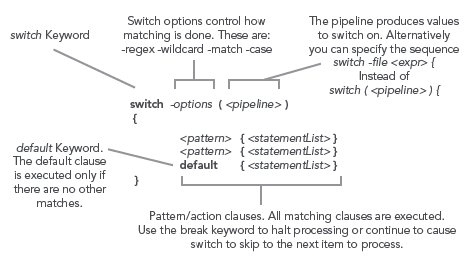

switch Statement: The PowerShell switch statement combines both branching and looping. It can be used to process collections of objects in the condition part of the statement or it can be used to scan files using the "file option.