Agile in the Defense Industry: Milestone Reviews

Defense programs have built-in checkpoints, with formal reviews and document deliveries more suitable for waterfall than agile. Agile programs find creative ways to make things work.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeThis is the third article in a series on the use of agile in the U.S. defense industry.

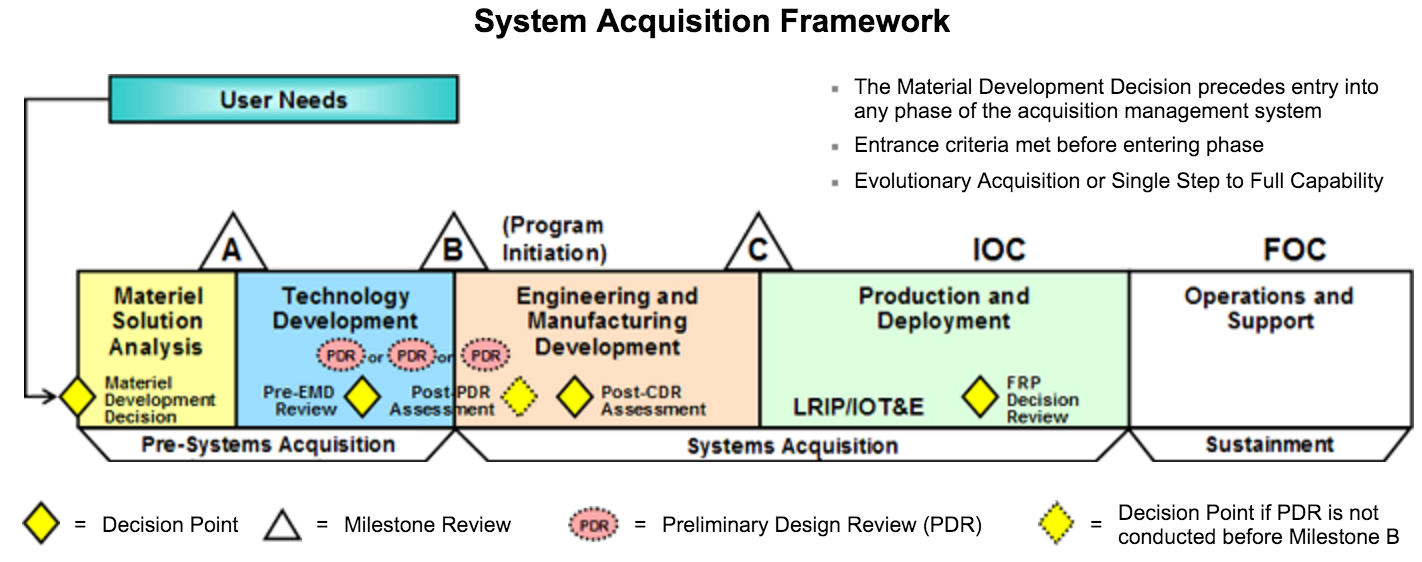

With characteristic dry aplomb, the Defense Acquisition Portal says, "[a]cquisition programs proceed through a series of milestone reviews and other decision points that may authorize entry into a significant new program phase." This helpful chart requires no further explanation:

Joking aside, when joining the defense industry, one is subject to a dizzying array of acronyms, terminology, and ways of doing things that have accumulated over the past several decades. The idea of "milestone reviews" is one of these.

The idea is, when we first start designing a new thing, we don't know very well what we need or how it will work. As we learn more, it makes sense to go through the decisions we've made so far and figure out whether what we're building will meet the needs of the people who are going to use it. Each phase costs more than the phase before it, and we want to avoid throwing good money after bad.

Like many ideas in the defense industry, this is very reasonable and came about as a logical reaction to problems on programs that didn't do this kind of review or didn't do it very well. Much of the process in the defense industry is "accumulated lessons learned", where an extra review step is added to avoid a problem that was seen before.

Of course, this kind of accumulation of extra steps leads to inefficiency and to cases where people aren't "allowed" to do the obvious and correct thing because the process gets in the way. At the same time, I have personally witnessed cases where people decided to chuck all the accumulated process in the bin, and the outcome wasn't good. It is important to remember the principle of Chesterton's Fence. (Similarly, Chesterton wrote, "[T]radition tells us not to neglect a good man's opinion, even if he is our father.")

In any event, on most defense programs the milestone reviews aren't going anywhere. From an engineering standpoint, there are four key milestone reviews that most programs go through: System Functional Review (SFR), Preliminary Design Review (PDR), Critical Design Review (CDR), and Test Readiness Review (TRR). The details of each of these reviews would be worth a whole article, but the key point I want to make is the implicit assumption in these reviews and their ordering. The whole thing is organized around the idea that first you establish the functions (requirements), then you do preliminary design, then detailed design, then you build it, then you test it. If ever the defense business deserved its stereotype of waterfall processes, this would be the time.

And this waterfall concept is only extended by the idea that milestone reviews "authorize entry" into a new "program phase". On a program where you can't write code until after the critical design review, and can't begin testing until after the test readiness review, where is the agile?

At this point, it's important to remember the original purpose of the milestone reviews. They are an opportunity to review the work that's been done to date, and make sure it meets the purpose of the system as our understanding has evolved. Of course, a good agile methodology has exactly this kind of review built in as a first-class feature! Whether we call them sprint reviews, backlog grooming, release planning, or something else, the idea with these activities is to look at what we've built and what we're planning to build in order to decide if we're providing value to the customer, and in order to make sure we're addressing the customer's highest priorities next.

So we're on solid theoretical ground with agile; we're not throwing away the valid insights that led to the use of milestone reviews. The remaining challenge is to figure out how to square the inherent waterfall bias of the milestone reviews with our desire to emphasize working software, customer collaboration, and responding to change. Of course, this is a big challenge, and it leads some programs to not really consider agile or to think it incompatible with defense programs. But I have seen teams be successful with approaches that, to me at least, appear to preserve the agile spirit.

First, it's important to note that while milestone reviews serve as a formal step in a program, good teams collaborate informally with the customer continuously. This is just common sense. The last place you want to surprise your customer is at a major design review when your boss and the customer's boss is present. So already we have an idea that the milestone review is a formal event that you don't hold until you're sure it's going to be successful.

Second, while a milestone review means that we create a "baseline" for some "deliverable" like a requirements or design document, changes continue to happen, no matter when that baseline is established. Good teams plan for that by making it easy to make and track changes after the baseline is established, and by making it easy to continue to deliver updates. This might mean, in cases where design documents are needed, generating those documents from the working software wherever possible. Or it might mean writing requirements in the form of test cases for a Behavior Driven Development (BDD) testing framework.

Third, every program manager knows that it's risky to work on an entire huge system for months and months, then hold a major review on the whole thing. It's very easy to convince a program manager to reduce the program's schedule risk by breaking the system up into separate components. Then, even if there is one big "capstone" review to satisfy the formal milestone, in practice the individual components have been designed and implemented iteratively, with continuous customer collaboration. And every program manager knows that schedule risk goes way down as the amount of working software goes up, so convincing them that it's OK to start implementation on some small pieces that we understand is also not generally hard as long as someone knows how to speak program manager language.

All of these together lead to what we might call an agile approach to milestone reviews. Start by looking for opportunities to review material (user stories, design approaches, code, tests) informally as it's produced, keeping the customer in the loop. Break the work up into small pieces and allow those pieces to move forward independently. Schedule the formal milestone review as a way to assemble and declare victory on the work that's already been done and reviewed by the customer. All of this serves the real purpose of the milestone review, which is to make sure that we are "building the right thing" as well as "building the thing right", so it's not like we're "dodging process".

Of course, all of this is written on the idea that the program has a traditional structure but is incorporating agile where possible. The U.S. Department of Defense is taking agile very seriously, and more programs are explicitly incorporating concepts from agile into program planning. On these programs, the traditional functional and design reviews can be explicitly replaced by sprint and release demonstrations. Regrettably, these kinds of programs are still somewhat rare and tend to be reserved for prototype and "technology development" programs.

Hopefully by this point I haven't scared off people who would otherwise have considered a career in the defense field. The key takeaway is that, while documented approaches sound very waterfall, the defense industry has always incorporated the idea of change and evolution, and over the past several years the industry is explicitly and dramatically taking up the ideas of agile and rethinking existing activities in light of agile ideas. In the next article, I'll discuss how testing has generally been performed and how it is evolving.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments