ASP.NET Session Hijacking with Google and ELMAH

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeI love ELMAH – this is

one those libraries which is both beautiful in its simplicity yet

powerful in what it allows you to do. Combine the power of ELMAH with

the convenience of NuGet and you can be up and running with absolutely

invaluable error logging and handling in literally a couple of minutes.

Yet,

as the old adage goes, with great power comes great responsibility and

if you’re not responsible with how you implement ELMAH, you’re also only

a couple of minutes away from making session hijacking of your ASP.NET

app – and many other exploits – very, very easy. What’s more, vulnerable

apps are only a simple Google search away. Let me demonstrate.

Update:

I want to make it clear right up front that the out of the box ELMAH

configuration does not make any of what you’re about to read possible.

It’s only when ELMAH is configured to expose logs remotely and not properly secured that things go wrong.

The ELMAH value proposition

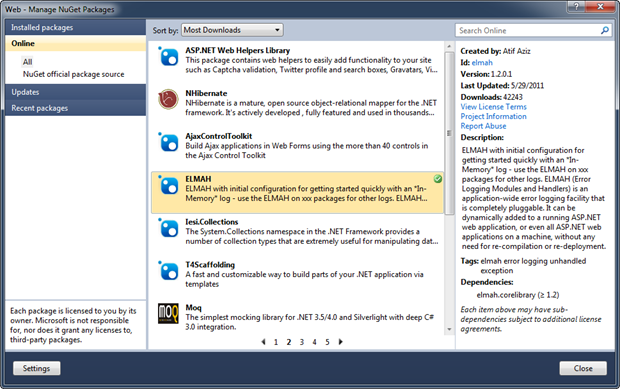

Some background first; ELMAH is the Error Logging Modules and Handlers written by the very clever Atif Aziz and it’s very popular. How popular? It’s presently the 14th most downloaded package on NuGet:

What this means is that at the time of writing, there have been 42,429 downloads of the library.

I

suspect the popularity has a lot to do with how simple it is to

implement. First of all, you can add ELMAH to your ASP.NET app without a

recompile; it’s simply a matter of some web.config entries and

including the ELMAH library.

Secondly, it’s very easy to log

errors to a number of different persistent storage mechanisms including

the default in-memory store and to SQL Server (among others) for a bit

more longevity. Once the web.config is set up, it just happens automagically.

Thirdly,

it’s very simple to configure ELMAH to fire you off an email when

something goes wrong. There’s nothing like being able to actually

contact a user with a “Hey, I see you were having a problem” message

five minutes after they’ve had issues. People love that sort of

proactivity!

Fourthly, it’s very easy to retrieve log entries,

you just head off to the /elmah.axd path of the app which invokes a nice

little handler to pull recent messages out of whatever repository

you’re using.

And finally, ELMAH logs have really, really useful

stuff in them for helping you actually fix the problem. But as it turns

out, they also have really, really useful stuff in them for helping the

bad guys break the application which brings us neatly to the purpose of

today’s post.

Hacker-friendly info in ELMAH

Let’s

start delving into the detail of what ELMAH gives us, or in this case

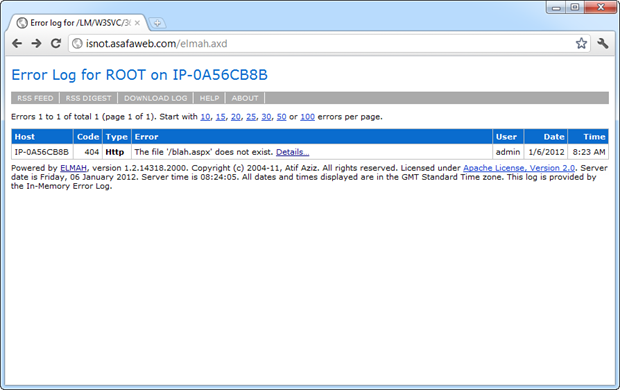

today, what it gives the hacker. Here’s an example of what comes out of

that elmah.axd handler:

Actually, you can see this for yourself over at http://isnot.asafaweb.com/elmah.axd

This particular site is one I use as a test bed for ASafaWeb and its deliberately

insecure (more on that shortly). What you’re seeing in the image above

is a request for the path “/blah.aspx” which doesn’t exist hence it’s

causing an HTTP 404 “NOT FOUND” which is captured by ELMAH. So far, so

good.

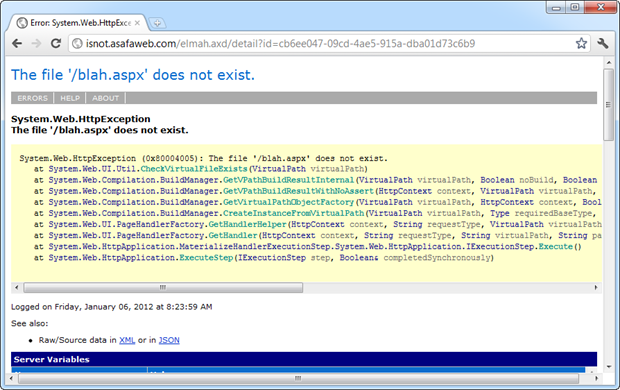

Drilling down into that error, we’ll see a stack trace

which begins to disclose the internal implementation of the code where

the error occurred. Keep in mind this is totally independent of the

custom errors configuration of the app; you can turn them on and provide

a default redirect to an error page and ELMAH will still log what you see below – that’s the beauty of it!

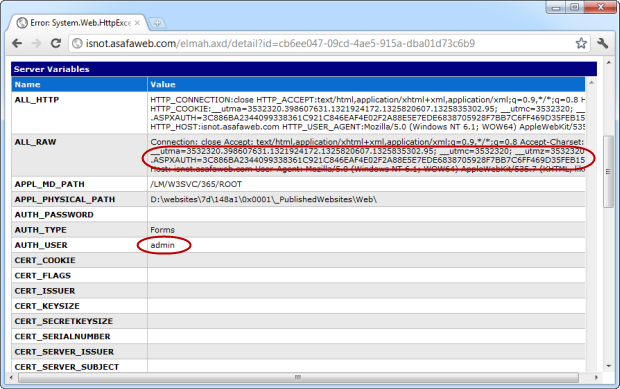

Now let’s scroll down a bit and get to the interesting section – server variables:

I’ve highlighted two sections here and I want to refer to them from the bottom up:

- The “AUTH_USER” variable is set to “admin”. This is the username of the authenticated user when the error occurred. In other words, we know it was the admin logged in at the time.

- The “.ASPXAUTH” cookie. In case this isn’t already familiar, take a look through my post about OWASP Top 10 for .NET developers part 9: Insufficient Transport Layer Protection

Read

the post? Right, so now you’ll have a good idea of where this post is

heading – the .ASPXAUTH cookie is used to persist the authenticated

state of a user when the website uses the ASP.NET membership provider

for authentication.

Identifying a target

The crux of

this exploit centres around the fact that many people are not properly

protecting ELMAH logs on their site and that it’s easily discoverable.

In fact it’s so easy to discover, it’s just a matter of a simple Google

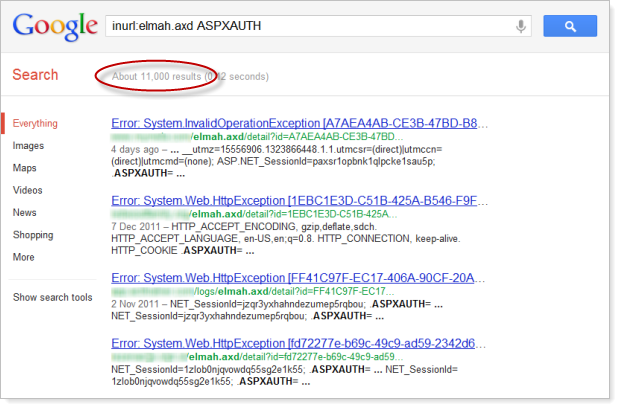

search for inurl:elmahtr.axd ASPXAUTH

Oh boy, that’s a lot of results – 11,000 unprotected ELMAH log pages with authentication cookie info! Substitute the “ASPXAUTH” criteria for “Error Log for” which appears at the top of every

elmah.axd resource and the result is presently 192,000. Ouch! Sure,

some of these results are for the same site and some are simply pages about ELMAH but whichever way you cut it, there are a huge number of sites putting their privates on public display!

This is your classic Googledork

or in other words, a carefully crafted search which turns up results

related to careless configuration. Keep in mind also that this is

obviously only the publicly accessible results which Google has indexed;

how many more sites are out there exposing their ELMAH logs that simply

haven’t been indexed? After all, elmah.axd is normally not a publicised

resource; Google has to know it’s there and explicitly request the

resource for indexing.

Exploiting the website

Now for

the interesting bit – leveraging the info above to actually exploit the

website. Let me paint a scenario which puts the ease and practicality of

this into context:

Wearing my evil hacker hat, I’ve just done

the Google search above and identified the site I want to exploit. I can

see from the logs that the ASPAUTH cookie is being captured so I know

that forms authentication is being used or in other words, the site has

something that it wants to protect. From this search alone there’s a

good change I could find a valid ASPXAUTH token to use in my hijacking

exercise.

But what if the log is just using the default

in-memory storage and has recently been flushed? Or there are no recent

errors with an ASPAUTH cookie which is still valid? No problem, just a

little bit of social engineering is required to help generate a new

error message. Finding contact details for the site owner is usually

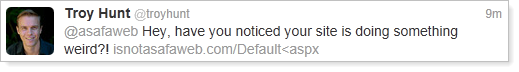

simple, let’s try a message like this (I’m assuming @asafaweb is the target):

The

inclusion of the “<” character in the URL will cause request

validation to fire – everything else in the message is just intended to

build a sense of urgency (the message) and legitimacy (the domain of the

URL). Now of course the user needs to be authenticated in order to get a

new ASPAUTH cookie, but chances are they’re either already logged in or

are using a long-lasting timeout to save them logging back in. Even if

they’re not, a similarly crafted message with a link to an admin page

could easily take care of this.

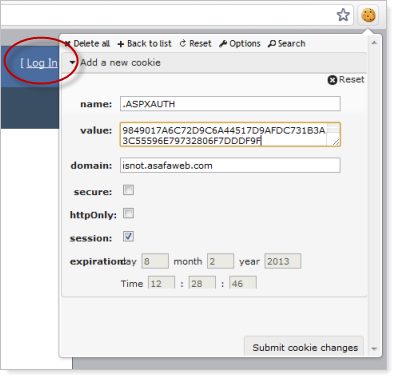

Now it’s just a matter of the

attacker watching ELMAH until a new log entry appears. The auth cookie

will look something like this:

.ASPXAUTH=3C886BA2344099338361C921C846EAF4E02F2A88E5E7EDE6838705928F7BB7C6FF469D35FEB1532C44B81DB38F200DEE08B6ED0E6121B945C659E932D8CE8B69FFF09E7B59DBE4820873DBD7891DD6B6BC4A486F35A2F99849017A6C72D9C6A44517D9AFDC731B3A3C55596E79732806F7DDDF9F

With our hacker hat on, let’s now take this value and create a new cookie with the name and value from above. This becomes very simple with a browser extension like Edit This Cookie:

You

can see the “Log In” text behind the cookie window so this browser is

definitely not authenticated before adding the cookie. But if the hacker

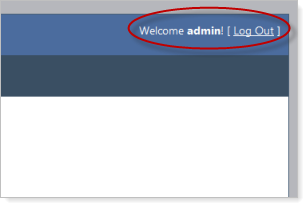

submits the cookie and refreshes the page:

And there you have it – the hacker is now logged in as an admin! This doesn’t give them the admin password, but it does them all the rights of the admin user.

Depending on the system, this may give them the rights to view or

create other accounts, manage permissions, view financial data, etc.

etc. Use your imagination.

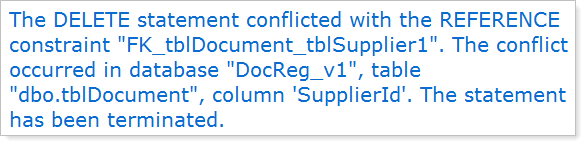

But wait – there’s more

A

publicly exposed ELMAH log is pretty serious business vulnerability

wise. There’s not just the risk of session hijacking as explained here,

for example there’s the risk of disclosing internal database structure

just by searching for SqlException:

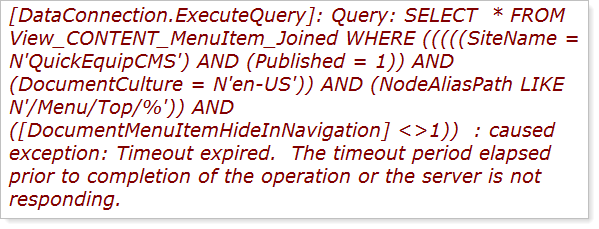

Or how about a bunch of SQL statements – this is just what you want to get a big head start on an injection attack:

Or how about simply searching for “password” – you don’t even need to look beyond the search window on some of these:

Want to find sites using a particular library in which a zero-day has just been discovered? And this is absolutely, positively only an example – I’m just picking a popular library which wouldn’t normally be discoverable by just browsing the site:

But

of course it’s not just about searching for existing errors which might

be of interest, once an attacker knows a site is exposing ELMAH logs

they can then go and attempt a whole range of other attacks and get immediate feedback about what’s going on internally! How convenient is that?!

But

there’s also a whole raft of other little snippets which might come in

valuable to the evil doers; referring URLs, physical path of the site on

the server, physical path of the site on the machine it was compiled on

(often the developer’s machine), the names and values of all the

cookies, the IP address of visitors to the site and so on and so forth.

ELMAH logs are a treasure trove of information.

Protecting against this attack

This is really just a simple case of access controls or in OWASP speak, Failure to Restrict URL Access. This is not – and let me really emphasise this – is not a vulnerability in ELMAH.

In

a case where the membership and role providers are being used, the fix

is nothing more complex than a simple authorisation entry in the

web.config:

<location path="admin">

<system.web>

<httpHandlers>

<add verb="POST,GET,HEAD" path="elmah.axd"

type="Elmah.ErrorLogPageFactory, Elmah" />

</httpHandlers>

<authorization>

<allow roles="Admin" />

<deny users="*" />

</authorization>

</system.web>

<system.webServer>

<handlers>

<add name="Elmah" path="elmah.axd" verb="POST,GET,HEAD"

type="Elmah.ErrorLogPageFactory, Elmah"

preCondition="integratedMode" />

</handlers>

</system.webServer>

</location>

It’s important to note that the ELMAH handler has been moved into the

“admin” path; failure to do this may allow elmah.axd to be mapped to

other paths such as “/foo/elmah.axd”. This would mean the logs could be

accessed even if the path “elmah.axd” were to be secured as the

authorisation rule would only apply to the handler in the root of the

site.

Update 11 Jan: The guidance above has been slightly modified based on the discussion in the comments below.

It seems that the original guidance on the ELMAH website which I

reproduced here allowed the same elmah.axd handler to be requested from

other paths hence bypassing the authorisation. Bugger!

That’s it, nothing more. Those 192,000 sites from the Googledork search do not have this!

Each of those sites is easily vulnerable to the attack above. They’re

also exposing internal stack traces and server variables which may lead

to attacks of other natures. This is a serious, serious configuration

vulnerability.

Oh, and just in case it’s not already obvious, transport layer

protection does absolutely nothing to mitigate this risk, it just means

an attacker can load your sensitive log data over an encrypted

connection :)

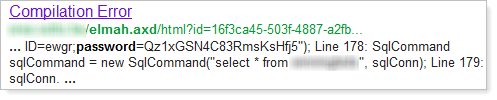

A helping hand from ASafaWeb

In fairness to those with publicly facing ELMAH logs, this is really

easy to get wrong. The ease of implementation ELMAH offers makes it

both powerful and potentially vulnerable at the same time. In fact

that’s often the story with .NET in general; features like custom errors

and stack traces can very easily be exposed entirely by accident.

Last month I launched ASafaWeb

with the intention of providing a free tool to easily check for ASP.NET

configuration related vulnerabilities. Today I’m happy to also add a

scan for the public accessibility of ELMAH.

I’m very careful with any scans I add to ASafaWeb. Usually this means

an additional HTTP request (as is the case with the ELMAH scan), and

these are very costly little exercises in terms of the duration it adds

to a scan. But in the case of ELMAH, the prevalence of the library

combined with the enormous number of insecure sites and the ease of

implementation makes it a good candidate to add.

Here’s how it works; the ASafaWeb website

allows you to either plug in a URL (this can be any publicly accessible

URL) or alternatively, run a scan against the sample site I referred to

above and have highlighted below:

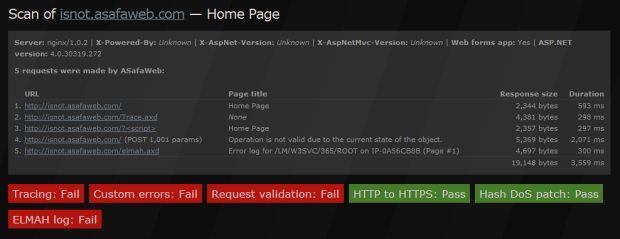

When the scan runs, there are a series of HTTP requests made in order

to test various aspects of the site security. ASafaWeb shows you what

the specific requests were then the status of each individual scan.

Sometimes more than one HTTP request is used for a scan or a single request can be reused across multiple scans:

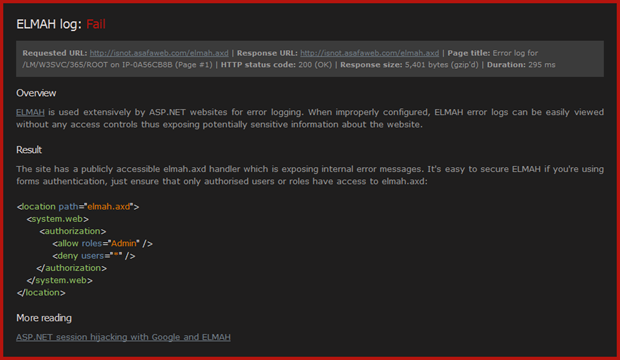

Clicking on the failing “ELMAH log” scan then jumps us down the page

to the details of the scan including the path with the vulnerability and

how to fix it (essentially the information in the post above):

You can deep link directly into the scan of the test site if you’d like to see it in action now.

Summary

In case I didn’t make it perfectly clear the first few times, this is

not a flaw in ELMAH, in fact I think it’s a fantastic tool and I use it

extensively in ASafaWeb: https://asafaweb.com/Admin/elmah.axd

Whoops, you can’t access that though, can you?! And that’s really the

point I’m making – ELMAH can be implemented securely and everything

above is no way a recommendation not to use it. But please, please, apply a little due diligence and lock it down properly.

If you do discover your ELMAH logs were publicly visible then

decide to lock them down, there’s still the real risk they’ve already

been indexed and cached versions are still available, in fact I saw this

several times when researching for this post. If you’re in this camp,

you want to take a good look at what’s in your (now secure) ELMAH logs

and consider what information may have been exposed and is now

searchable via the various search engines (remember, it’s not just

Google).

Source: http://www.troyhunt.com/2012/01/aspnet-session-hijacking-with-google.html

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments