Design Patterns for Microservice-To-Microservice Communication

Let's learn about design patterns for synchronous and asynchronous communication between microservices.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeIn my last blog, I talked about Design Patterns for Microservices. Now, I want to deep more deeply into the most important pattern in microservice architecture: inter-communication between microservices. I still remember when we used to develop monolithic applications; communication used be a tough task. In that world, we had to carefully design relationships between database tables and map with object models. Now, in the microservice world, we have broken them down into separate services, and that creates a mesh around them to communicate with each other. Let's talk about all the communication styles and patterns that have evolved so far to resolve this.

Many architects have divided inter-communication between microservices into synchronous and asynchronous interaction. Let's take these one by one.

Synchronous

When we say synchronous, it means the client makes a request to the server and waits for its response. The thread will be blocked until it receives communication back. The most relevant protocol to implement synchronous communication is HTTP. HTTP can be implemented by REST or SOAP. Recently, REST has been picking up rapidly for microservices and winning over SOAP. For me, both are good to use.

Now let's talk about different flows/use cases in the synchronous style, the issues we face, and how to resolve them.

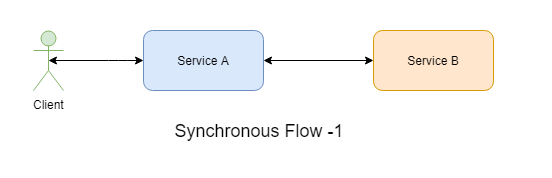

- Let's start with a simple one. You need a Service A calling Service B and waiting for a response for live data. This is a good candidate to implement the synchronous style as there are not many downstream services involved. You would not need to implement any complex design pattern for this use case except load balancing, if using multiple instances.

![Image title]()

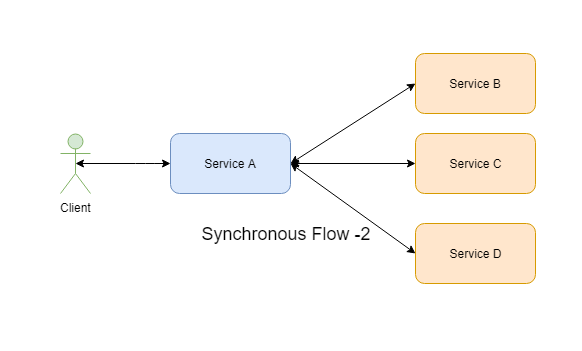

- Now, let's make it little more complicated. Service A is making calls to multiple downstream services like Service B, Service C, and Service D for live data.

- Service B, Service C, and Service D all have to be called sequentially — this kind of scenario will be there when services are dependent on each other to retrieve data or the functionality has a sequence of events to be executed through these services.

- Service B, Service C, and Service D can be called in parallel — this kind of scenario will be used when services are independent of each other or Service A may be doing an Orchestrator role.

This scenario brings the complexity while doing the communication. Let's discuss them one by one.

Tight Coupling

Service A will have tight coupling with each Service B, C, and D. It has to know each service's endpoint and credentials.

Solution: The Service Discovery Pattern is used to solve this kind of issues. It helps to decouple the consumer and producer app by providing a lookup feature. Services B, C, and D can register themselves as services. Service discovery can be implemented server side as well as client-side. For the server side, we have AWS ALB and NGINX tools, which accept requests from the client, discover the service, and route the request to the identified location.

For the client side, we have Spring Eureka discovery service. The real benefit of using Eureka is that it caches the available services information on the client side, so even if Eureka Server is down for some time, it doesn't become a single point of failure. Other than Eureka, other service discovery tools like etcd and consul are also used widely.

Distributed Systems

If Service B, C, and D have multiple instances, they need to know how to do the load balancing.

Solution: Load balancing generally goes hand-in-hand with service discovery. For server-side load balancing, AWS ALB can be used and for the client side, Ribbon or Eureka can be used.

Authenticating/Filtering/Handling Protocols

If Service B, C, and D need to be secured and need authentication, we need to filter through only certain requests for these services and if Service A and other services understand different protocols.

Solution: API Gateway Pattern helps to resolve these issues. It can handle authentication, filtering and can convert protocols from AMQP to HTTP or others. It can also help enable observability metrics like distributed logging, monitoring, and distributed tracing. Apigee, Zuul, and Kong are some of the tools which can be used for this. Please note that I suggest this pattern if Service B, C, and D are part of managed APIs, otherwise its overkill to have an API Gateway. Read further down for service mesh as an alternate solution.

Handling Failures

If any of Services B, C, or D is down and if Service A can still serve client requests with some of the features, it has to be designed accordingly. Another problem: let's suppose that Service B is down and all the requests are still making calls to Service B and exhausting the resources as it's not responding. This can make whole system go down and Service A will not be able to send requests to C and D as well.

Solution: The Circuit Breaker and Bulkhead pattern helps to address these concerns. The circuit Breaker pattern identifies if a downstream service is down for a certain time and trips the circuit to avoid sending calls to it. It retries to check again after a defined period if the service has come back up and closes the circuit to continue the calls to it. This really helps to avoid network clogging and exhausting resource consumption. The bulkhead helps isolate the resources used for a service and avoid cascading failures. Spring Cloud Hystrix does this same job. It applies both Circuit Breaker and Bulkhead patterns.

Microservice-to-Microservice Network Communication

An API Gateway is generally used for managed APIs where it handles requests from UIs or other consumers and makes downstream calls to multiple microservices and responds back. But when a microservice wants to call to another microservice in the same group, the API Gateway is overkill and not meant for that purpose. It ends up that individual microservice takes the responsibility to make network communications, do security authentication, handle timeouts, handle failures, load balancing, service discovery, monitoring, and logging. It's too much overhead for a microservice.

Solution: The service mesh pattern helps to handle these kind of NFRs. It can offload all the network functions we discussed above. With that, microservices will not call directly to other microservicse, but go through this service mesh, and it will handle the communication with all features. The beauty of this pattern is that now you can concentrate on writing business logic in any language — like Java, NodeJS, or Python — without worrying if these languages have the support to implement all network functions or not. Istio and Linkerd address these requirements. The only thing i don't like about Istio is that it is limited to Kubernetes as of now.

Asynchronous

When we talk about asynchronous communication, it means the client makes a call to the server, receives acknowledgment of the request, and forgets about it. The server will process the request and complete it.

Now let's talk about when you need the asynchronous style. If you have an application which is read-heavy, the synchronous style might be a good fit, especially when it needs live data. However, when you have write-heavy transactions and you can't afford to lose data records, you may want to choose asynchronous because, if a downstream system is down and you keep sending synchronous calls to it, you will lose the requests and business transactions. The rule of thumb is to never ever use async for live data read and never ever use sync for business-critical write transactions unless you need the data immediately after write. You need to choose between availability of the data records and strong consistency of the data.

There are different ways we can implement the asynchronous style:

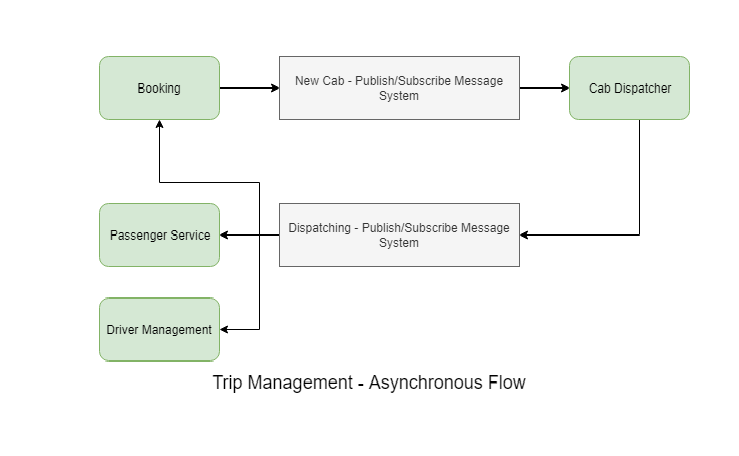

Messaging

In this approach, the producer will send the messages to a message broker and he consumer can listen to the message broker to receive the message and process it accordingly. There are two patterns within messaing: one-to-one and one-to-many. We talked about some of the complexity synchronous style brings, but some of it is eliminated by default in the messaging style. For example, service discovery becomes irrelevant as the consumer and producer both talk only to the message broker. Load balancing is handled by scaling up the messaging system. Failure handling is in-built, mostly by the message broker. RabbitMQ, ActiveMQ, and Kafka are the best-known solutions in cloud platforms for messaging.

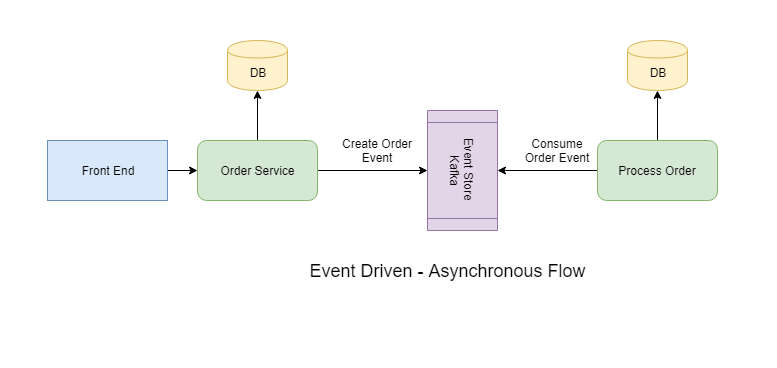

Event-Driven

The event-driven method looks similar to messaging, but it serves a different purpose. Instead of sending messages, it will send event details to the message broker along with the payload. Consumers will identify what the event is and how to react to it. This enables more loose coupling. There are different types of payloads that can be passed:

- Full payload — This will have all the data related to the event required by the consumer to take further action. However, this makes it more tightly coupled.

- Resource URL — This will be just a URL to a resource that represents the event.

- Only event — No payload will be sent. The consumer will know based on on the event name how to retrieve relevant data from other sources, like databases or queues.

There are other styles, like choreography style, but I personally don't like that. It is too complicated to be implemented. This can only be done with the synchronous style.

That's all for this blog. Let me know your experience with microservice-to-microservice communication.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments