Designing a Usable, Flexible, Long-Lasting API

Let's take a look at how to design a usable, felxible, and long-lasting APi. Also explore the best practices.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeThis article is featured in the new DZone Guide to API Management: Comparative Views of Real World Design. Get your free copy for more insightful articles, industry statistics, and more!

I remember the final commit like it was yesterday, even though it was several years ago. Six months of work building our application, and we were ready to launch. It followed all of the best practices, the code was perfect (OK, maybe adequate), and it was just in time for the big release. Like an episode of Silicon Valley, we waited to for the numbers— numbers that never came. Instead, after six months of work, we watched as customers expressed interest and then just walked away.

We designed a solution our customers didn't need. Panic set in, and we spent the next three to four weeks quickly refactoring the code, trying to make it something they could use. But it was too little, too late. In the end, the company spent around $1 million on a project that was discarded in the trash, all because we forgot one simple rule: Building an API is easy. Designing a usable, flexible, long-lasting API is hard.

While this experience sticks with me, it also surprises me how so many small and large businesses alike forget this simple rule. If you don't understand what it is you're building, why you're building it, or who you're building it for — how can it truly meet their needs? How can it meet your needs? How can it be successful?

Who, What, Where, Why, and How

Before your design your API, you need to know who you're building it for. Is it for internal consumers, customers, third-party developers, or all of the above?

Once you answer the who, the next question becomes simpler: What do they need access to? Commonly, this step gets confused with the HTTP methods (GET, POST, PUT, PATCH), but instead, at this junction, you should be able to list what actions they need.

As you start thinking about the actions your users need to be able to do, place them in a chart, like so:

| Users | Create user, edit user, reset password, suspend user, message user |

| Messages | Create draft, send message, read message, delete message |

This chart, while rudimentary, offers significant advantages from the get-go. If you're building a RESTful API, you've already identified your resources (in this case, users and messages). The chart also forces you to think through the workflows. Finally, it helps reduce duplication by making us think through where certain endpoints should live; in this case, it doesn't make sense to have an endpoint for messaging users under /users if we have a resource /messages. It does, however, make sense to have a link from the users object to the message (allowing us to build out a hypermedia map as we go).

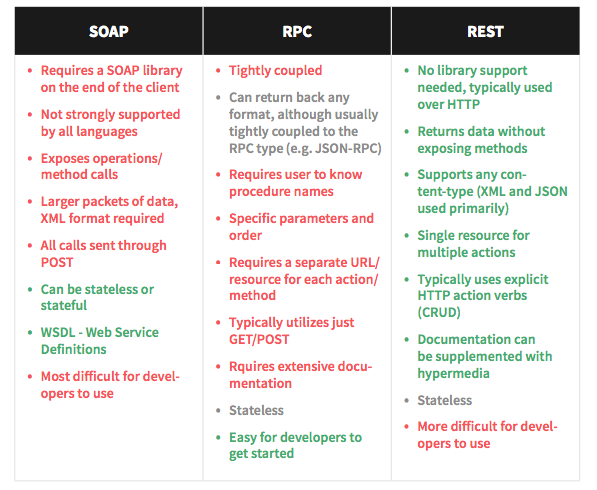

The next step of the process is to understand why we're building the type of API we are. This step is important — it forces us to consider the specific reasons we're choosing that format over others and to understand the format we're choosing.

Most APIs aren't truly REST APIs, so if you choose to build a RESTful API, do you understand the constraints of REST including hypermedia/HATEOAS? If you choose to build a partial REST or REST-like API, do you know why you are choosing to not follow certain constraints of REST?

Depending on what your API needs to be able to do and where your API will be used, legacy formats such as SOAP may make sense. However, with each format comes a tradeoff in terms of usability, flexibility, and development costs.

Finally, as we start to plan our API, it's important to understand how our users will interact with the API and how they'll use it in conjunction with other services. Be sure to use tools like RAML or Swagger/OAI during this process to involve your users, provide mock APIs for them to interact with, and to ensure your design is consistent and meets their needs.

Best Practices

As you design your API, it's also important to remember that you're laying a foundation to build upon at a later time. One of the easiest ways to kill an API is to try to reinvent the wheel or improve upon existing standards/ideas in production without heavily testing them first.

In other words, as a developer, don't get fancy. Build on tested and tried best practices that your consumers will be expecting within your API.

Nouns vs. Verbs

When building a RESTful or REST-like API, utilize nouns as resources.

You should be using /users and then relying on the HTTP methods instead of relying on /getUser or /deleteUser. Another more controversial best practice is to use plural naming conventions for any resources that return collections. Keep in mind that even if the resource only currently returns a single item, if there's the possibility to return multiple items, then it should be created as a collection.

For example, you might have a resource /address that only returns one address. But what happens when you allow for a billing address, shipping address, or multiple addresses? From day one, you should call the resource /addresses and return the address back in an array so that the application evolves to eventually allow for multiple addresses and the contract remains intact.

Accept and Content-Type Headers

A best practice to avoid costly refactors is utilizing accept and content-type headers. Regardless of whether your API only accepts JSON or XML today, there may come a time when you're required to add additional formats.

By building in the context-switcher from the start, adding any new formats is as simple as adding the appropriate libraries behind-the-scenes and allowing that format type, letting you easily support multiple formats without refactoring your RESTful API.

Use of Http Methods

Because actions of a RESTful or REST-like API are dictated by HTTP methods, it's important to understand what each method does and when to use it. Perhaps it's easiest to use CRUD:

CREATE — POST

READ — GET

UPDATE — PUT, PATCH

DELETE — DELETE

While many of the HTTP methods seem pretty clear, the RFC standards allow for unique usage for each. For example, POST is a magical method that can be used for most operations; however, that doesn't mean that it should. Instead, rely on POST to create a new item in a collection or create a new record. Also, while POST makes sense on a collection, it may not make sense at an item level.

PUT is another unique method — it can be used to create a new record if it doesn't exist (but only if an explicit ID is provided, the record doesn't exist, and a 201 status is returned), or used to update an existing record. It's important to remember that many developers aren't familiar with the create aspect of PUT, and many frameworks don't test to see if the result is a 200 or 201. As such, they may receive a successful response when expecting a 404 NotFound. Be very wary of using PUT to create new records, even in those specific situations, unless necessary and well-documented within your API.

PATCH is widely suggested as an alternative to PUT, as it will PATCH the data record with the data it receives.

Also keep in mind that you probably do not want to allow PUT, PATCH, or DELETE on a collection, as that would essentially update or delete all of the items in that collection.

Descriptive Error Messages

Along with understanding how to use your API, it's important to understand why something didn't work when using your API. I can't tell you the number of APIs I've used where the error message is simply"something went wrong" or "invalid parameter." These messages do nothing to assist the developer in using your API.

Instead, provide clear, relevant error messaging. Don't just tell the user that an ID is missing — tell them why they need the ID to begin with. If there's an internal support code that they can use when emailing your team, give them that code. Most importantly, provide a link to documentation that shows them how to fix the error. You don't have to recreate the wheel or guess what should be in the error message.

There are several great formats that already exist today including Google Errors, JSON API, and vnd.error.

Use Hypermedia

While HATEOAS (Hypermedia as the Engine of Application State)sounds extreme, its purpose is simple: remove the business logic from the client.

Think of how APIs are built today: The client receives a response, and based on that response, needs to determine what actions it can take against the user. It can do this by utilizing the OPTIONSmethod (if the API allows for it) or making the calls to see if they work (getting a 200 or 400), or the developer can mimic the business logic on the client and hope nothing changes.

HATEOAS uses links to tell the client what actions can be taken next. If a business rule changes, the link changes — meaning there'sno rework on the client or developer's end. This is crucial because it also allows for the separate evolution of the client and server.

Take, for example, three users: one is an admin, one is a standard user, and one was caught spamming. Most likely, the application state of each object is different. The super user can't be deleted, the standard user can be suspended, and the suspended user can't be suspended again. The links returned in the response explain the state of each one of these users in a way that doesn't require the client to know the underlying business rules.

Perhaps the most common example of hypermedia can be found on the world wide web. If you visit DZone.com, you don't have to type in the URL of the article you're looking for. You go to DZone.com, click a link, click another link, and eventually end up where you want to be. This all occurs because of HTML (hypertext markup language).

While HTML is perhaps the most common form of hypermedia, there are several popular formats you can use for your API today, including HAL and JSON API. As these specifications mature, we're also seeing newer formats like Siren and CPHL — which extend the HAL format with the HTTP methods, forms, code on demand, and flexible documentation.

Example of HAL/CPHL in an API:

{

"firstName": "Mike",

"lastName": "Stowe",

"_links": {

"edit": {

"href": "/users/1",

"methods": [

"put",

"patch"

]

},

"message": {

"href": "/message?to=1",

"methods": [

"post"

]

}

}

}Hypermedia also allows for contractual flexibility. Say you have a messaging resource and hypothetically, one of your users accidentally places it in an infinite loop, causing 10,000 sends before hitting their limit. To solve this issue, you add a token to the resource — but if the resource is hard-coded, you've broken the contract, meaning you need to version your API and all of your clients need to update their code.

With hypermedia, since they're relying on a key:value, the URL can change or the token can be added without breaking the contract or causing any inconveniences for your users.

In other words, it's a simple change to the above response like so that lets you put in an additional check without breaking yourAPI's contract:

"message": {

"href": "/

message?to=1&token=893hdy83ikaherukaehfiwf7w48ika",

"methods": ["post"]

}To Recap

Building an API is easy but designing an API that is flexible enough to last years, evolving as your platform evolves, is hard — let alone adding in usability. These best practices, along with tools like RAML or Swagger/OAI can help you make that challenge a reality. But it's up to you to ensure that you take the time, involve your users, and think through every aspect of your API. Like a foundation, one stone in the wrong place can cause the whole thing to tumble — and with an API, it only takes one little thing to significantly reduce its lifespan.

This article is featured in the new DZone Guide to API Management: Comparative Views of Real World Design. Get your free copy for more insightful articles, industry statistics, and more!

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments