User Personas and Pipeline Facades for Effective Release Decisions

This article discusses using user personas with CI/CD pipelines to learn which data your business needs, and the importance of how data is presented.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeThis article is featured in the new DZone Guide to DevOps. Get your free copy for more insightful articles, industry statistics, and more!

Continuous Deployment (putting changes live in production as soon as they pass a fully automated delivery pipeline) is a hard sell in most organizations. That's partially because release decisions often need to involve different areas of the business (marketing and compliance, to name but a few), even if all the technical bits have been automated.

Continuous Delivery, on the other hand, is really about making timely, well-informed release decisions, unhindered by technical constraints (as the delivery pipeline gives us confidence that all the required technical activities have been performed successfully):

“Continuous Delivery is the ability to get changes of all types into production, or into the hands of users, safely and quickly in a sustainable way.” — Jez Humble

Our interpretation of "sustainable" in this context, and from years of consulting experience, is that we need to put the right information in front of the right people, at the right time, and in the right format for them to consume.

Delivery Pipelines Are Treasure Troves of Data for Release Decision-Making

Typical usages of pipeline information include activity execution time (in a rather static fashion: "How long is our build? How long are our acceptance tests?") and artifact traceability ("Which code changes were deployed to production between version X and Y?"). Sometimes, information is collected for external auditors ("Who approved this change and when?").

More advanced use cases include historical trends on execution time ("our acceptance tests take 20% longer to run than 6 months ago") or overall cycle time ("on average a user story takes 2.5 days since initial commit until it's in production"). However, there's a lot more data available in our pipeline tooling, especially if we're using a toolchain made up of single-purpose, API-driven tools. In fact, a lot of data is logged but not even displayed via the tool's UI, or not with an associated semantic.

Making Use of Personas to Understand What Data Our Business Needs

User personas are a representation of a class of users of our system, personified as an individual with specific needs, skills, goals, and frustrations. This concept originated in the UX community and is widely used in design processes.

Thinking of users in terms of personas helps build empathy and design systems that are a better fit for the jobs they need to get done and that avoid known obstacles.

Turns out this is an effective way to understand internal users as well, not only customers. So, we can apply them to understand the information needs of our business stakeholders when it comes to making release decisions.

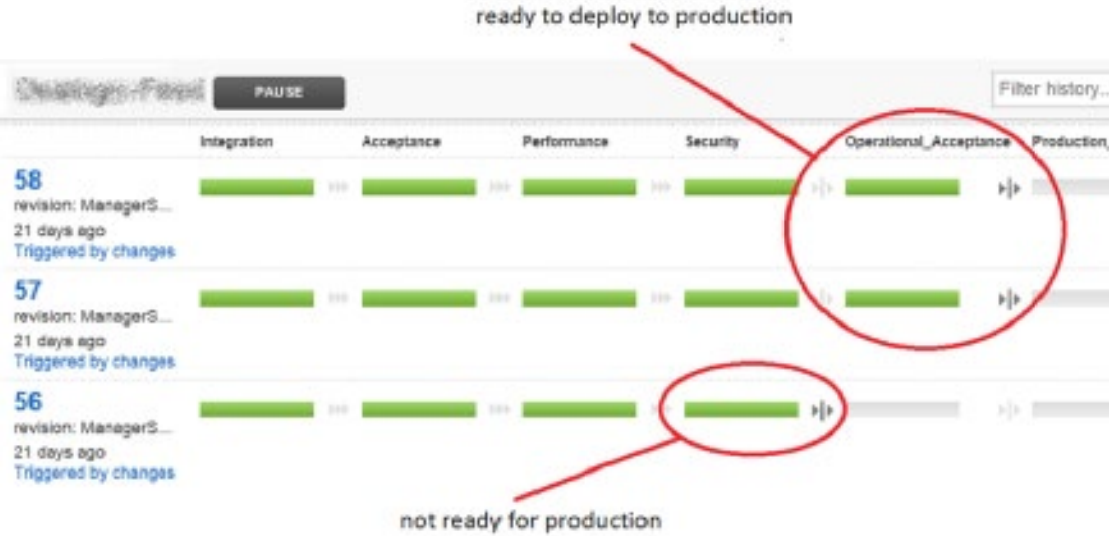

Let's imagine Amy is a product owner who is waiting for an exciting new feature to be ready to deploy to production. She found out today from the developers in the standup meeting that the changes are ready. After confirming that the related work item has been updated in JIRA, she now finds this scenario in their pipeline tool:

She knows pipeline #56 is not ready for production because it did not reach “Operational Acceptance” stage. But what about pipelines #57 and #58?

Amy reaches out to developers, testers, and ops folks to understand what are the differences and impact of deploying the changes in pipeline #57 versus those in pipeline #58.

By the end of the day, she learns that pipeline #57 is safer to deploy to production, as pipeline #58 includes some backwards compatible database changes needed for a different feature. Tests are passing, but it's peak season for the business and we can't afford downtime or issues during DB migration.

Amy needs to coordinate with marketing for them to launch a social media campaign as soon as the feature is available to customers, so deployment will have to wait for tomorrow.

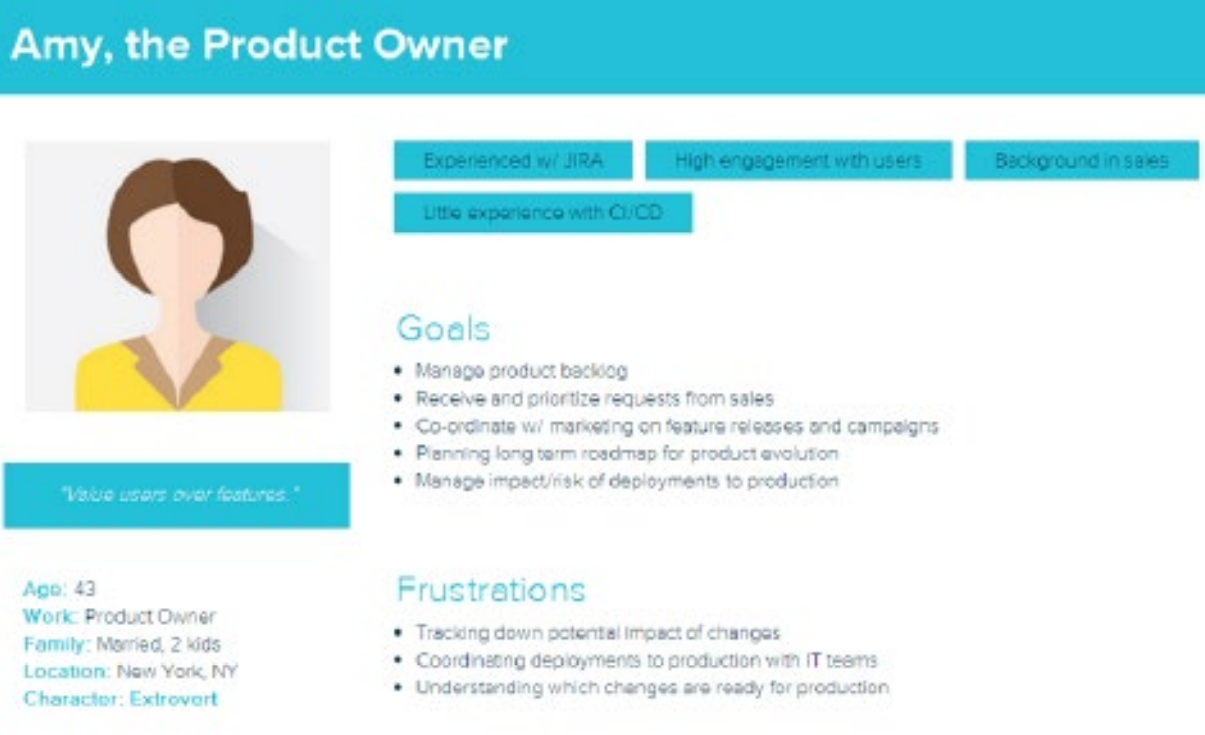

The interesting bit here is that had we mapped out the user persona for Amy (as a representative of the product owner stakeholder), we would have found out she's not familiar with our pipeline tooling, that she often needs to synchronize with marketing and other teams on the timing for a release, and that her frustration level increases when it takes her the better part of a working day to find out the impact of deploying one set of changes versus another.

Amy's user persona highlights common traits, goals, and frustrations of product owners in the organization.

How Data Is Presented Is as Important as the Data Itself

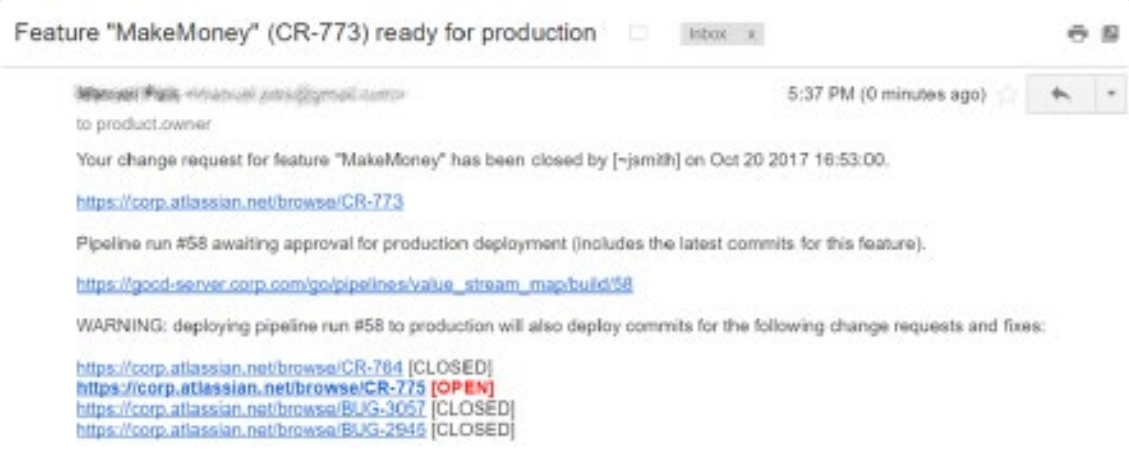

Now, let's imagine Amy gets an email notification like this every time a feature request is closed.

Pipeline façade in the form of a notification email collecting data from JIRA and GoCD.

At a glance, without any coordination effort, Amy is informed that pipeline #58 contains the completed feature, but changes for another request have creeped in. She quickly accesses the item under work (CR-775) and asks John, the assigned developer, about the status. After double checking with the DBA team, Amy syncs with marketing and they agree on deploying the previous version instead (pipeline #57).

Because we provided Amy with the data she needed in a format that is familiar and easy to consume, we drastically reduced the time to make a release decision. There is still some coordination and analysis involved, but all the running around and frustration is greatly reduced.

This is just an example. The point is not about this specific use case or implementation, but rather to be aware that non-technical stakeholders are part of our delivery chain too. By identifying internal personas, we can better understand how to present them with the information they need in a way that reduces friction and time to decide.

Design Pipeline Façades to Push the Right Information in the Right Format

A façade is a software design pattern whereby a single, minimal interface abstracts away the complexity of a larger body of code. The actual implementation might need to make multiple calls to other parts of the code and even merge or transform data between formats in order to provide its consumers what they need and nothing more.

We can do exactly the same with our delivery pipeline: design façades that collect information from the different tools involved and transform it as necessary to provide non-technical stakeholders an actionable, filtered data view. The pipeline and toolchain technicalities are no longer obstacles, making our delivery more inclusive.

Because we are not restricted to a specific programming language, implementing these pipeline façades can take multiple forms: a simple query, an email notification, a webpage, a database view, etc.

The hard part is not implementing, but understanding which implementation better fits our personas' needs, skills, and frustrations.

Let's consider another example, one which will increasingly be on the spotlight for any organization doing business in the European Union, as the new General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) comes into effect in May 2018. The GDPR enforces stricter data governance and consent management for user data. With fines up to 20 million euros, organizations will be forced to shift their data security and compliance processes left. Again, pipeline information can massively help in decision making for compliance with GDPR.

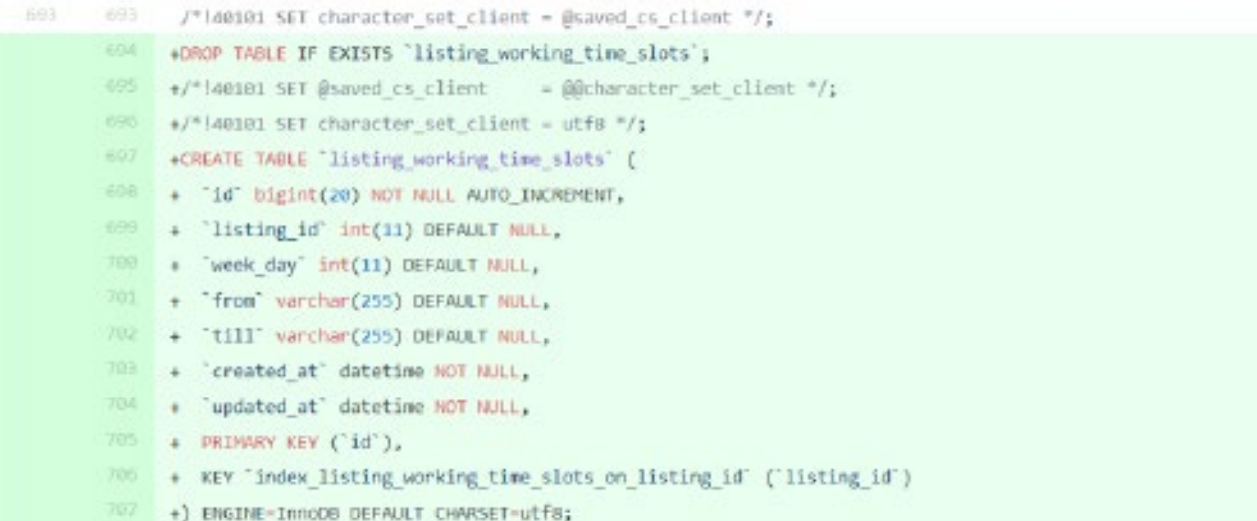

Assuming our database changes are stored in version control (either using database migrations or a database state versioning approach) and go through a pipeline just like any other code changes, quickly identifying relevant changes for data governance can prove massively helpful for Mark, our compliance officer. But how?

Let's imagine Mark has a technical background and is familiar with Oracle databases and SQL scripts. We're not database experts, but it's not a wild guess if we say he'll be quite interested to know when new tables, columns, or views get created, at the very least.

Because our system is based on the Ruby on Rails framework, we know all our database migration scripts are located under the db/migrate folder in source control, thus we can simply provide Mark a GitHub query URL with all commits in that folder containing the create_table instruction, right?

Except that those db migration scripts are written in Ruby, and Mark is only familiar with SQL. So instead of looking for commits, we might need to resort to diffing the SQL database state file that Rails generates after the migration scripts are applied. The good news is that all of this is available in our pipeline runs.

Also, Mark doesn't really care about all the databases our system handles, only those related to users. So, we need to filter out uninteresting results to make this usable. Mark would also like to see at a glance how and when these database changes have been tested and which data set was used to test them. All of these should be available in our pipeline, and thus possible to retrieve and present as well.

Now imagine instead that Mark had a pure legal background and was not technically savvy at all. We would need an extra data transformation step to translate the filtered-out SQL or Ruby into plain English statements. Possibly we could agree to detail how data will be stored (format, retention policy, etc.) in our commit comments and push them into the release information that Mark will receive.

Hopefully we have highlighted the point that how we make use and present the data in our pipelines for less technical stakeholders is the hard(er) part of making faster, more informed release decisions.

Short and Wide Pipelines Go Hand in Hand With Efficient Decision Making

Once you start cutting down the time it takes to make your release decisions, eventually the pipeline itself becomes the bottleneck, especially when all activities are serialized (each activity can only start when the previous has been completed, and all activities in the pipeline must be performed for all changes).

This is the time to think about making your pipelines short and wide instead, a pattern mentioned by Jez Humble. This means moving your pipeline from a sequential, long path to production, to one where we recurrently make decisions in terms of "for this set of changes, which activities in the pipeline must be performed before release?"

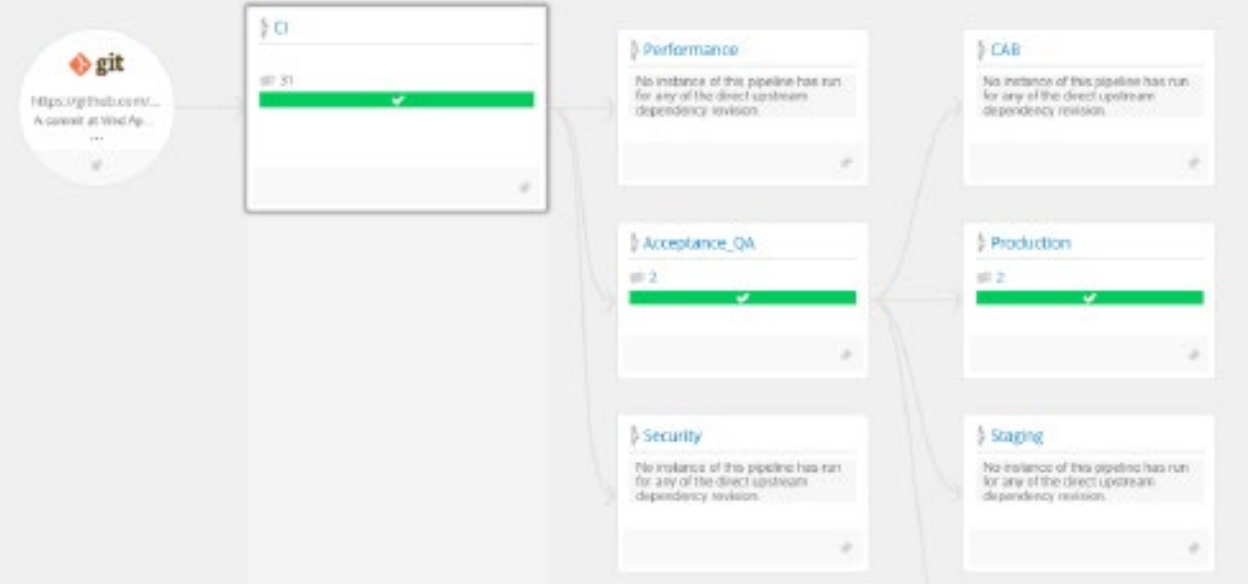

Example of a short and wide pipeline, with three mandatory activities for all changes, and four optional.

With a short and wide pipeline, all changes go through a minimum set of activities (for example, CI, acceptance tests, and deployment to production) but all other activities in the pipeline are optional (for example, performance tests or in-depth security tests).

Of course, the pipeline façade pattern can help us again to decide which activities we should perform before deploying to production, based on past deployments and success rate for similar type of changes.

Getting Started

First, identify what kind of decisions need to be made and by who for any non-trivial change to get released to production. If your pipeline already closely maps your value stream then this should be quite straightforward. Pick one, ideally the one causing the greatest delay in time from commit to production.

Second, write up a persona that approximates the characteristics of the group of persons in your organization (or division) fulfilling that decision-making role.

Third, talk to the people in that group and discuss what kind of information would help them make those decisions faster. Ask them to think beyond what they know today (current pipeline tool UI, for example).

Fourth, develop a first pipeline façade iteratively. Sketch out (paper prototyping is enough) a few different implementation options and assess usefulness (right data) and usability (right format). Iterate a couple of times at most until you have an MVP. Don't polish this too much, start using it rather quickly to actually validate if it helps your decision-making process.

Finally, once you've proven this approach, reach out to other delivery decision makers and engage with them to design pipeline façades that help them do their job more efficiently

This article is featured in the new DZone Guide to DevOps. Get your free copy for more insightful articles, industry statistics, and more!

Published at DZone with permission of Manuel Pais. See the original article here.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments