Go Microservices, Part 4: Testing and Mocking With GoConvey

This series on building microservices with Go continues by looking at challenges and strategies for unit testing with GoConvey.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For Freehow should one approach testing of microservices? are there any unique challenges one needs to take into account when establishing a testing strategy for this particular domain? in part 4 of this blog series, we will take a look at this topic.

- the subject of testing microservices in the unit context

- write unit tests in the bdd-style of goconvey

- introduce a mocking technique

since this part won't change the core service in any way, no benchmarks this time.

first of all, one should keep the principles of the testing pyramid in mind.

unit tests should form the bulk of your tests as integration-, e2e-, system- and acceptance tests are increasingly expensive to develop and maintain.

secondly - microservices definitely offers some unique testing challenges and part of those is just as much about using sound principles when establishing a software architecture for your service implementations as the actual tests. that said - i think many of the microservice-specifics are beyond the realm of traditional unit tests which is what we're be going to deal with in this part of the blog series.

anyway, a few bullets i'd like to stress:

- unit test as usual - there's nothing magic with your business logic, converters, validators etc. just because they're running in the context of a microservice.

- integration components such as clients for communicating with other services, sending messages, accessing databases etc. should be designed with dependency injection and mockability taken into account.

- a lot of the microservice specifics - accessing configuration, talking to other services, resilience testing etc. can be quite difficult to unit-test without spending ridiculous amounts of time writing mocks for a rather small value. save those kind of tests to integration-like tests where you actually boot dependent services as docker containers in your test code. it'll provide greater value and will probably be easier to get up and running as well.

source code

as before, you may checkout the appropriate branch from the cloned repository to get the completed source of this part up front:

git checkout p4

introduction

unit testing in go follows some idiomatic patterns established by the go authors. test source files are identified by naming conventions. if we, for example, want to test things in our handlers.go file, we create the file handlers_test.go in the same directory. so let's do that.

we'll start with a sad path test that asserts that we get an http 404 if we request an unknown path:

package service

import (

. "github.com/smartystreets/goconvey/convey"

"testing"

"net/http/httptest"

)

func testgetaccountwrongpath(t *testing.t) {

convey("given a http request for /invalid/123", t, func() {

req := httptest.newrequest("get", "/invalid/123", nil)

resp := httptest.newrecorder()

convey("when the request is handled by the router", func() {

newrouter().servehttp(resp, req)

convey("then the response should be a 404", func() {

so(resp.code, shouldequal, 404)

})

})

})

}this test shows the "given-when-then" behaviour-driven structure of goconvey and also the "so a shouldequal b" assertion style. it also introduces usage of the httptest package where we use it to declare a request object as well as a response object we can perform asserts on in a convenient manner.

run it by moving to the root "accountservice" folder and type:

> go test ./...

? github.com/callistaenterprise/goblog/accountservice[no test files]

? github.com/callistaenterprise/goblog/accountservice/dbclient[no test files]

? github.com/callistaenterprise/goblog/accountservice/model[no test files]

ok github.com/callistaenterprise/goblog/accountservice/service0.012swonder about ./... ? it's us telling go test to run all tests in the current folder and all subfolders. we could also go into the /service folder and type go test which then would only execute tests within that folder.

since the "service" package is the only one with test files in it the other packages report that there are no tests there. that's fine, at least for now!

mocking

the test we created above doesn't need to mock anything since the actual call won't reach our getaccount func that relies on the dbclient we created in part 3 . for a happy-path test where we actually want to return something, we somehow need to mock the client we're using to access the boltdb. there are a number of strategies on how to do mocking in go. i'll show my favorite using the stretchr/testify/mock package.

in the /dbclient folder, create a new file called mockclient.go that will be an implementation of our iboltclient interface.

package dbclient

import (

"github.com/stretchr/testify/mock"

"github.com/callistaenterprise/goblog/accountservice/model"

)

// mockboltclient is a mock implementation of a datastore client for testing purposes.

// instead of the bolt.db pointer, we're just putting a generic mock object from

// strechr/testify

type mockboltclient struct {

mock.mock

}

// from here, we'll declare three functions that makes our mockboltclient fulfill the interface iboltclient that we declared in part 3.

func (m *mockboltclient) queryaccount(accountid string) (model.account, error) {

args := m.mock.called(accountid)

return args.get(0).(model.account), args.error(1)

}

func (m *mockboltclient) openboltdb() {

// does nothing

}

func (m *mockboltclient) seed() {

// does nothing

}

mockboltclient can now function as our explicitly tailored programmable mock. as stated above, this code implicitly implements the iboltclient interface since the mockboltclient struct has functions attached that matches the signature of all functions declared in the iboltclient interface.

if you dislike writing boilerplate code for your mocks, i recommend taking a look at mockery which can generate mocks for any go interface.

the body of the queryaccount function may seem a bit weird, but it is simply how strechr/testify provides us with a programmable mock where we have full control of its internal mechanics.

programming the mock

let's create another test function in handlers_test.go :

func testgetaccount(t *testing.t) {

// create a mock instance that implements the iboltclient interface

mockrepo := &dbclient.mockboltclient{}

// declare two mock behaviours. for "123" as input, return a proper account struct and nil as error.

// for "456" as input, return an empty account object and a real error.

mockrepo.on("queryaccount", "123").return(model.account{id:"123", name:"person_123"}, nil)

mockrepo.on("queryaccount", "456").return(model.account{}, fmt.errorf("some error"))

// finally, assign mockrepo to the dbclient field (it's in _handlers.go_, e.g. in the same package)

dbclient = mockrepo

...

}next, replace the ... above with another goconvey test:

convey("given a http request for /accounts/123", t, func() {

req := httptest.newrequest("get", "/accounts/123", nil)

resp := httptest.newrecorder()

convey("when the request is handled by the router", func() {

newrouter().servehttp(resp, req)

convey("then the response should be a 200", func() {

so(resp.code, shouldequal, 200)

account := model.account{}

json.unmarshal(resp.body.bytes(), &account)

so(account.id, shouldequal, "123")

so(account.name, shouldequal, "person_123")

})

})

})this test performs a request for the known path /accounts/123 which our mock knows about. in the "when" block, we assert http status, unmarshal the returned account struct and asserts that the fields match what we asked the mock to return.

what i like about goconvey and the given-when-then way of writing tests is that they are really easy to read and have great structure.

we might as well add another sad path where we request /accounts/456 and assert that we get an http 404 back:

convey("given a http request for /accounts/456", t, func() {

req := httptest.newrequest("get", "/accounts/456", nil)

resp := httptest.newrecorder()

convey("when the request is handled by the router", func() {

newrouter().servehttp(resp, req)

convey("then the response should be a 404", func() {

so(resp.code, shouldequal, 404)

})

})

})finish by running our tests again:

> go test ./...

? github.com/callistaenterprise/goblog/accountservice[no test files]

? github.com/callistaenterprise/goblog/accountservice/dbclient[no test files]

? github.com/callistaenterprise/goblog/accountservice/model[no test files]

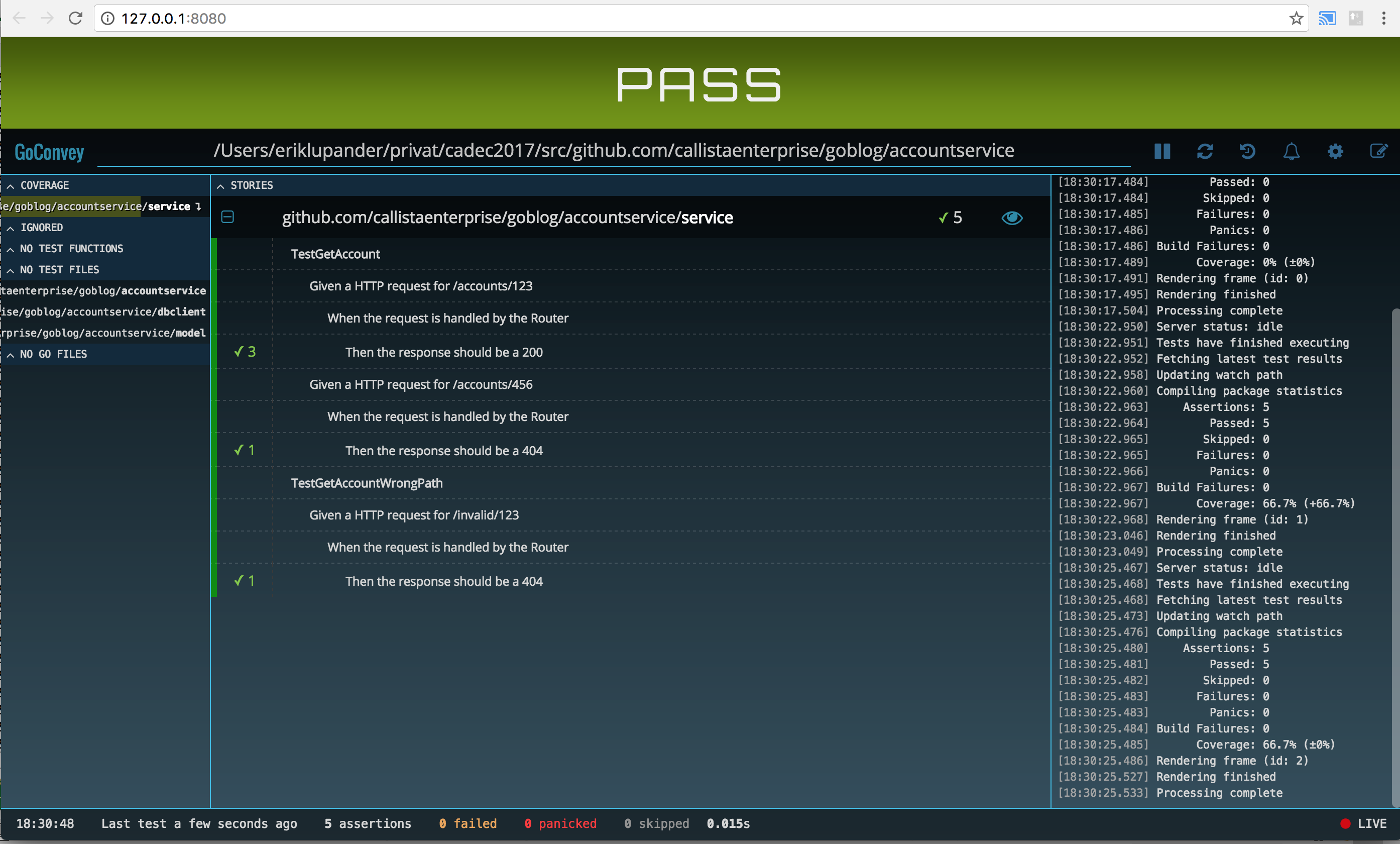

ok github.com/callistaenterprise/goblog/accountservice/service0.026sall green! goconvey actually has an interactive gui that can execute all tests everytime we save a file. i won't go into detail about it but looks like this and also provides stuff like automatic code coverage reports:

these goconvey tests are unit tests through the bdd-style of writing them isn't everyone's cup of tea. there are many other testing frameworks for golang, a quick search using your favorite search engine will probably yield many interesting options.

if we move up the testing pyramid we'll want to write integration tests and finally acceptance-style tests perhaps using something such as cucumber. that's out of scope for now but we can hopefully return to the topic of writing integration tests later on where we'll actually bootstrap a real boltdb in our test code, perhaps by using the go docker remote api and a pre-baked boltdb image.

another approach to integration testing is automating deployment of the dockerized microservice landscape. see for example the blog post i wrote last year where i use a little go program to boot all microservices given a .yaml specification, including the support services and then performing a few http calls to the services to make sure the deployment is sound.

in this part we wrote our first unit tests, using the 3rd party goconvey and stretchr/testify/mock libraries to help us. we'll do more tests in later parts of the blog series .

in the next part , it's time to finally get docker swarm up and running and deploy the microservice we've been working on into the swarm.

Published at DZone with permission of Erik Lupander, DZone MVB. See the original article here.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments