What Are Protocol Buffers?

In this post, follow a software engineer's experience in a project that required Protocol Buffers on a memory-constrained embedded system.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeOn a daily basis, I deal with custom software development and take part in projects for various industries. I specialize in the use of Modern C++ in embedded systems and building applications using Qt. Here, I will share with you my experience in a project that required Protocol Buffers on a memory-constrained embedded system. Let's take a look!

Imagine a situation where several people meet and each of them speaks a different language. To understand each other, they start to use a language that everyone in the group understands. Then, each of them wanting to say something has to translate their thoughts, which are usually in their mother tongue, into the language of the group.

We can then say that each of them performs some form of encoding and decoding information between the language of the group and the particular mother tongue.

If we change the individual languages into programming languages, and the group language into the Protocol Buffers message language, we get one of the advantages of Protocol Buffers; that is, the ability to create messages in a specific programming language that is known to the whole group and the ability to translate it into the form a language known only to a specific group member.

In addition to being language- and platform-independent, and the ability to encode and decode data, Protocol Buffers can do it quickly and efficiently.

According to Wikipedia, "Protocol Buffers are widely used at Google for storing and interchanging all kinds of structured information. The method serves as a basis for a custom remote procedure call (RPC or Remote procedure call) system that is used for nearly all inter-machine communication at Google."

Protocol Buffers logo

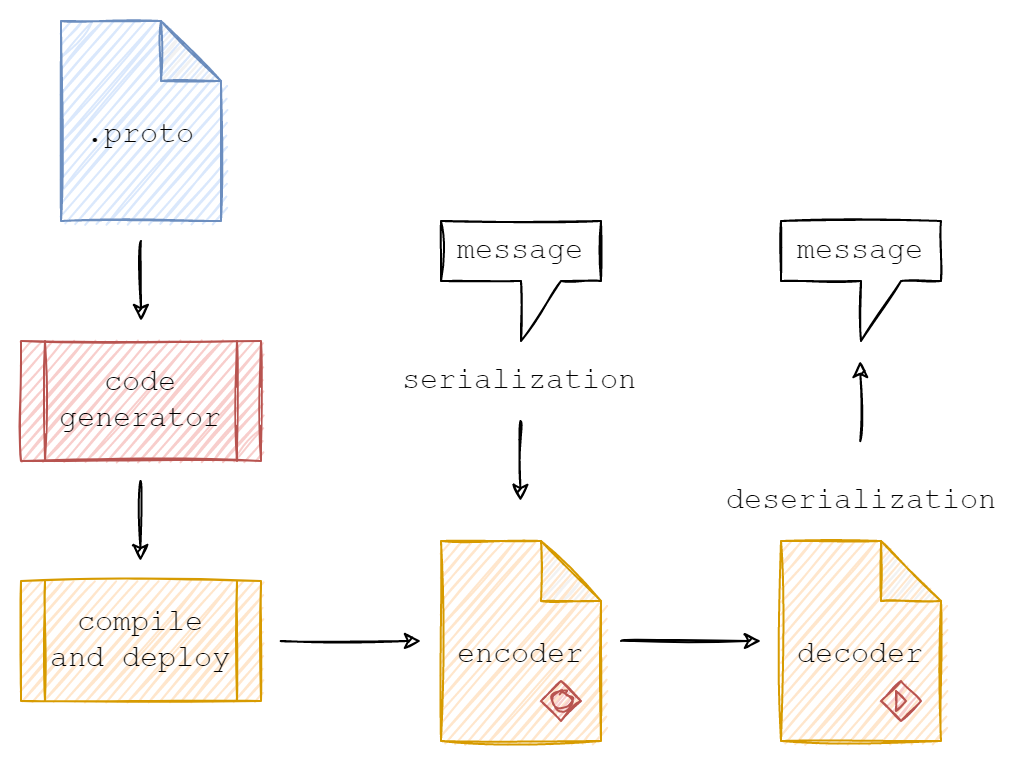

Protocol Buffers Message Language

As stated by Google, "Protocol buffers give you the ability to define how you want your data to be structured once(in a form of .proto file), then you can use special generated source code to easily write and read your structured data to and from a variety of data streams and using a variety of languages."

The Protocol Buffers Language Guide continues: "First, let's look at a very simple example. Let's say you want to define a Person message format, where each person has a name, age, and email. Here's the .proto file used to define this message type:

// person.proto

syntax = "proto3";

message Person {

string name = 1;

int32 age = 2;

string email = 3;

}The first line of the file specifies that you're using proto3 syntax."

The Person message definition specifies three fields (name/value pairs), one for each piece of data that you want to include in this type of message. The field has a name, a type, and a field number.

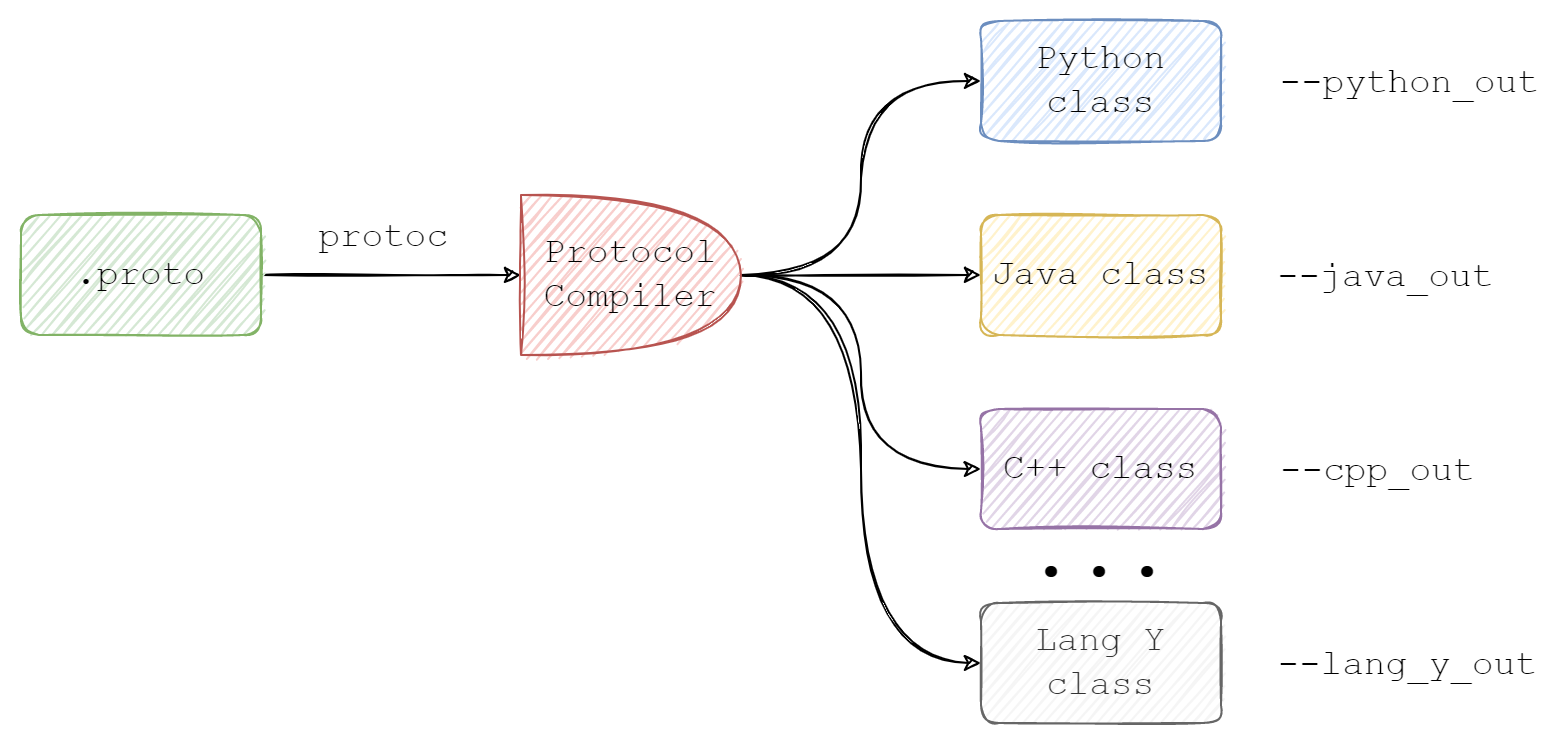

When you have your .proto file, you can generate source code for a specific language: for example, C++, using a special compiler called protocol compiler, aka protoc.

Protocol Compiler usage visualization

Generated files contain language-native structures to operate over the message Let’s call it API.

API provides you with all necessary classes and methods to set and retrieve data and as well as methods for serialization to and parsing from byte streams. Serialization and parsing are handled under the hood.

In the case of C++, the generated files contain the Person class and all necessary methods to work with underlying data. For example:

void clear_name();

const ::std::string &name() const;

void set_name(const ::std::string &value);

void set_name(const char *value);Additionally, Person class inherits methods from google::protobuf::Message to serialize to or deserialize (parse) from the stream:

// Serialization:

bool SerializeToOstream(std::ostream* output) const;

bool SerializePartialToOstream(std::ostream* output) const;

// Deserialization:

bool ParseFromIstream(std::istream* input);

bool ParsePartialFromIstream(std::istream* input);Static Allocations Using a Custom Allocator in Protobuf-C

If you are writing a fully statically allocated system, then probably you are using C instead of C++. Here you will find how to write a custom allocator which uses statically allocated buffer instead of dynamically allocated memory.

The Idea Behind

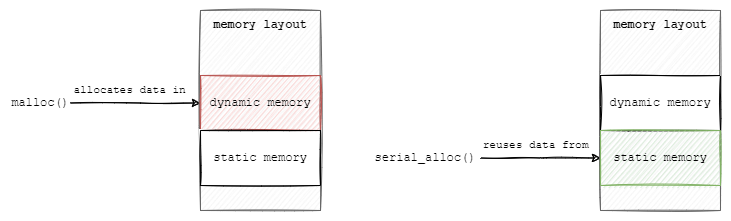

By default Protobuf-C when unpacking allocates memory dynamically by calling malloc(). Sometimes it's a no-go option in some embedded systems or resource-constrained systems.

Protobuf-C gives you the ability to provide a custom allocator - the replacement for malloc() and free() functions - in this example, the serial_alloc().

Difference between malloc() and serial_alloc() behavior

In this example, we will implement custom malloc() and free() functions, and use them in the custom allocator, the serial_allocator, which will be placing data into a contiguous, statically allocated block of memory by the Protobuf-C library.

The difference between how malloc() and serial_alloc() works, is represented in the diagram below.

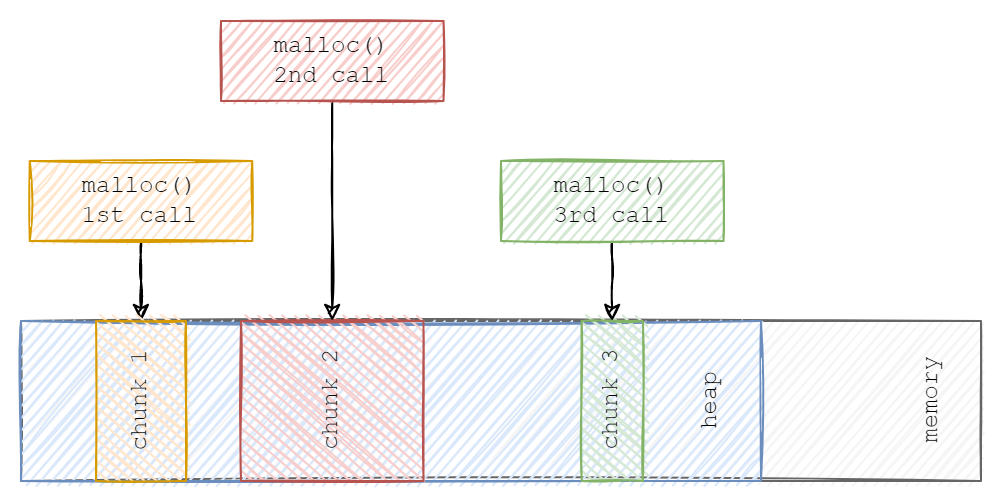

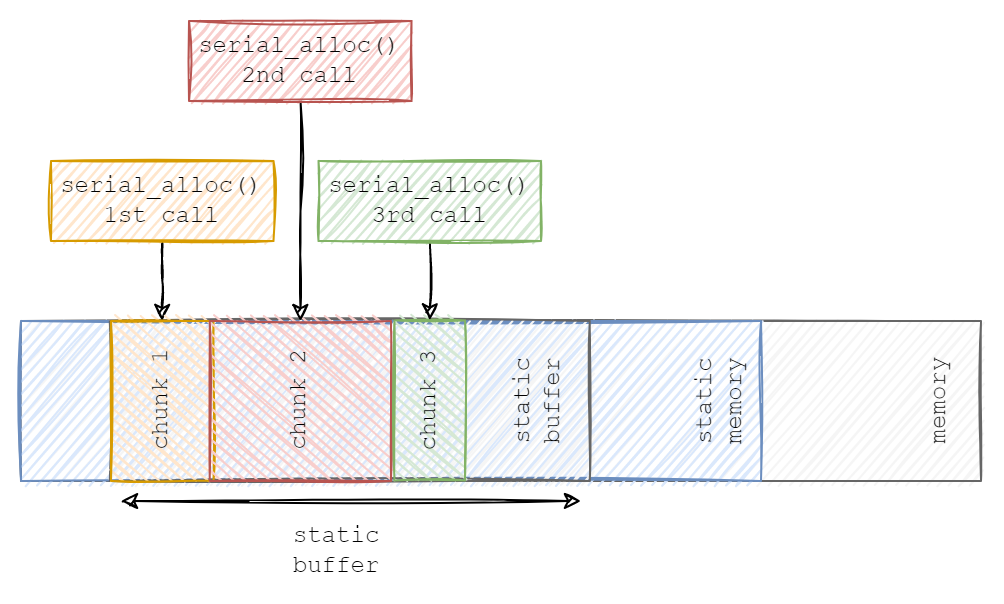

Representation of serial_alloc() “allocations” on the static buffer

In general, malloc() allocates memory “randomly” on the heap, leading to memory defragmentation. Our custom serial_alloc() “allocates” memory in sequence and on the statically allocated memory which leads to no heap usage and no memory defragmentation.

Environment Setup

The code shown in this article was tested on Ubuntu 22.04 LTS.

To install the protoc-c compiler and Protocol Buffers C Runtime, simply run:

sudo apt install libprotobuf-c-dev protobuf-c-compilerCheck if it works by running:

protoc-c --versionThat should return the installed versions:

protobuf-c 1.3.3

libprotoc 3.12.4If you need sources or need to build from sources, see the GitHub repository.

Message

In this example, a simple Message Protobuf message was created in message.proto file.

syntax = "proto3";

message Message

{

bool flag = 1;

float value = 2;

}Code Generation

To generate code, simply run:

protoc-c -I=. --c_out=. message.protoThis will generate two files: message.pb-c.h and message.pb-c.c.

Program Compilation

To compile your C program with generated code and link against the protobuf-c library, you simply run:

gcc -Wall -Wextra -Wpedantic main.c message.pb-c.c -lprotobuf-c -o protobuf-c-custom_allocatorCode Overview

In general, code does serialization/encoding/packing using Protobuf-C to static buffer pack_buffer, then does deserialization/decoding /unpacking to another static buffer, out:

#include "message.pb-c.h"

#include <stdbool.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

static uint8_t pack_buffer[100];

int main()

{

Message in;

message__init(&in);

in.flag = true;

in.value = 1.234f;

// Serialization:

message__pack(&in, pack_buffer);

// Deserialization:

unpacked_message_wrapper out;

Message* outPtr = unpack_to_message_wrapper_from_buffer(message__get_packed_size(&in), pack_buffer, &out);

if (NULL != outPtr)

{

assert(in.flag == out.message.flag);

assert(in.value == out.message.value);

assert(in.flag == outPtr->flag);

assert(in.value == outPtr->value);

}

else

{

printf("ERROR: Unpack to serial buffer failed! Maybe MAX_UNPACKED_MESSAGE_LENGTH is to small or requested size is incorrect.\n");

}

return 0;

}In unpack_to_message_wrapper_from_buffer(), we create the ProtobufCAllocator object and fill it with serial_alloc() and serial_free() functions (replacements for malloc() and free()). Then, we unpack message by calling message__unpack and passing serial_allocator:

Message* unpack_to_message_wrapper_from_buffer(const size_t packed_message_length, const uint8_t* buffer, unpacked_message_wrapper* wrapper)

{

wrapper->next_free_index = 0;

// Here is the trick: We pass `wrapper` (not wrapper.buffer) as `allocator_data`, to track number of allocations in `serial_alloc()`.

ProtobufCAllocator serial_allocator = {.alloc = serial_alloc, .free = serial_free, .allocator_data = wrapper};

return message__unpack(&serial_allocator, packed_message_length, buffer);

}Comparison of malloc()-Based vs serial_alloc-Based Approach

Below you can find the comparison between default Protobuf-C behavior (the malloc()-based), and custom behavior using a custom allocator:

Protobuf-C default behavior → using dynamic memory allocation:

static uint8_t buffer[SOME_BIG_ENOUGH_SIZE];

...

// NULL in this context means -> use malloc():

Message* parsed = message__unpack(NULL, packed_size, bufer);

// dynamic memory allocation occurred above

...

// somewhere below memory must be freed:

free(me)Protobuf-C uses a custom allocator → no dynamic memory allocations are used:

// statically allocated buffer inside some wrapper around the unpacked proto message:

typedef struct

{

uint8_t buffer[SOME_BIG_ENOUGH_SIZE];

...

} unpacked_message_wrapper;

...

// malloc and free functions replacements:

static void* serial_alloc(void* allocator_data, size_t size) { ... }

static void serial_free(void* allocator_data, void* ignored) { ... }

...

ProtobufCAllocator serial_allocator = { .alloc = serial_alloc,

.free = serial_free,

.allocator_data = wrapper};

// now, instead of NULL we pass serial_allocator:

if (NULL == message__unpack(&serial_allocator, packed_message_length, input_buffer))

{

printf("Unpack to serial buffer failed!\n");

}The most interesting parts are the unpacked_message_wrapper struct and serial_alloc() serial_free() implementations, which are explained below.

Struct Around the Proto Message

The unpacked_message_wrapper struct is just a simple wrapper around proto Message and a big enough buffer in the union to store unpacked data and next_free_index for track of used space in that buffer:

#define MAX_UNPACKED_MESSAGE_LENGTH 100

typedef struct

{

size_t next_free_index;

union

{

uint8_t buffer[MAX_UNPACKED_MESSAGE_LENGTH];

Message message; // Replace `Message` with your own type - generated from your own .proto message

};

} unpacked_message_wrapper;The size of the Message object will not change its size, but Message can be an extensive .proto (look at the "Tips and Tricks" section of this article) with, for example, repeated fields, which generally involve more than one malloc() call. So you may need more size, than the size of Message itself. To achieve this, the buffer and message members are in one union.

MAX_UNPACKED_MESSAGE_LENGTH must be big enough to fit the worst-case scenario. For more info check the "Tips and Tricks" section.

The purpose of the unpacked_message_wrapper struct is to keep in one place a predefined memory buffer and keep track of “allocations” on that buffer.

Implementation of serial_alloc() and serial_free()

The signature of serial_alloc() follows the ProtobufCAllocator requirements:

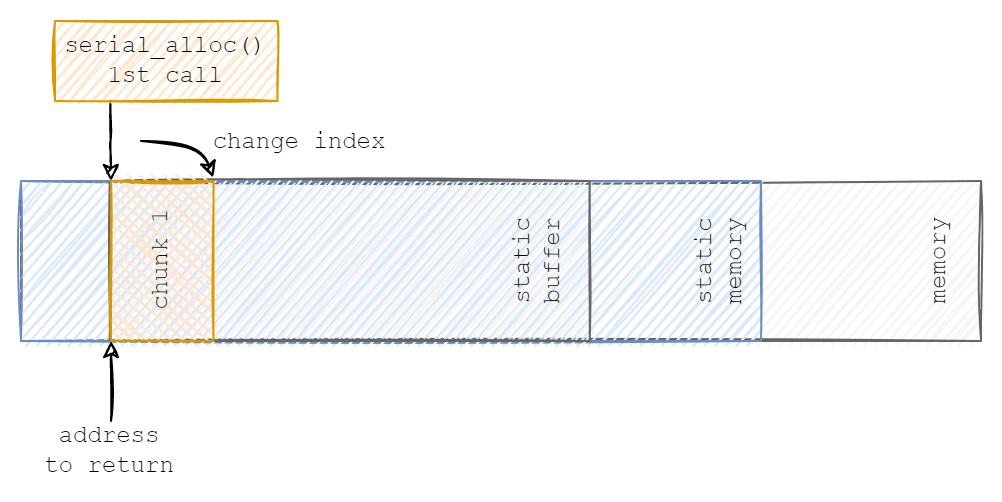

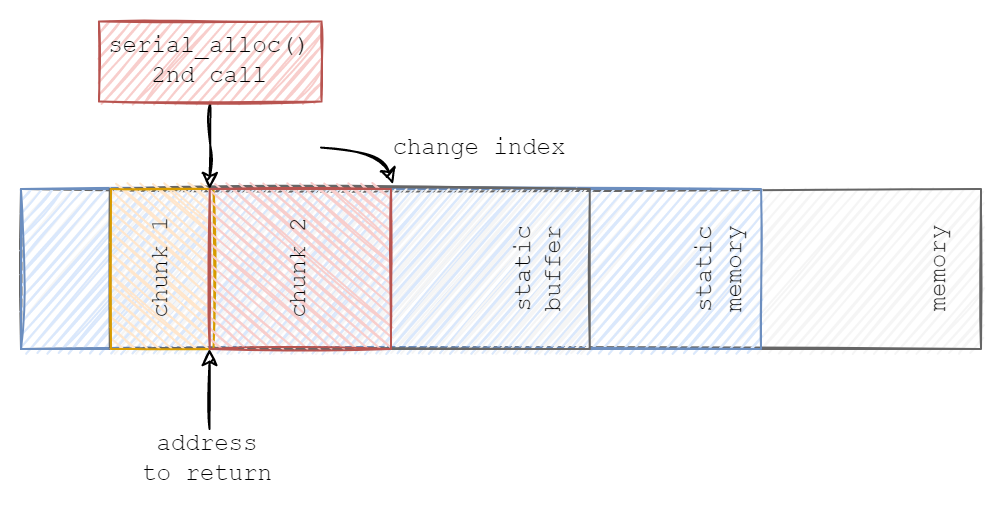

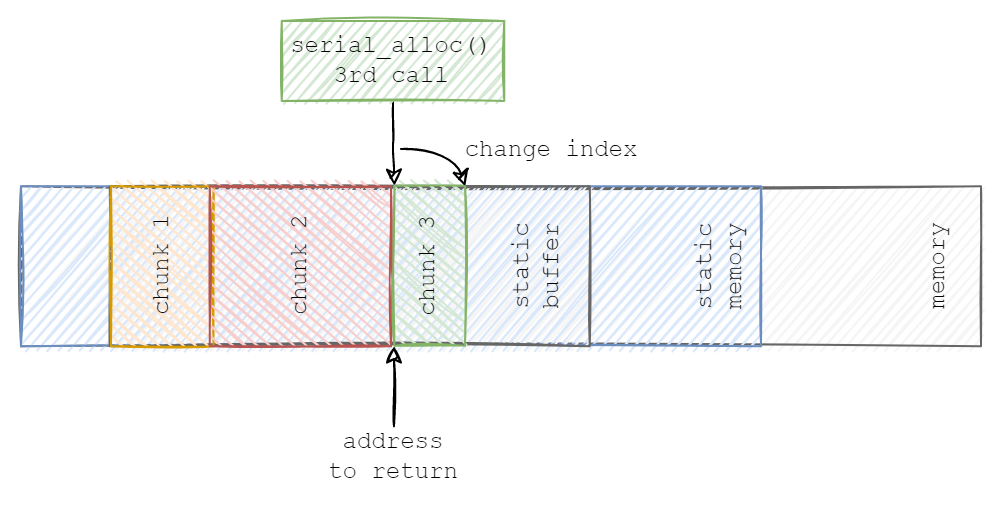

static void* serial_alloc(void* allocator_data, size_t size)serial_alloc() allocates the requested size on the allocator_data and then increments next_free_index to the start of the next word boundary (this is an optimization that aligns consecutive chunks of data to the next word boundary). size comes from Protobuf-C internals when parsing/decoding the data.

static void* serial_alloc(void* allocator_data, size_t size)

{

void* ptr_to_memory_block = NULL;

unpacked_message_wrapper* const wrapper = (unpacked_message_wrapper*)allocator_data;

// Optimization: Align to next word boundary.

const size_t temp_index = wrapper->next_free_index + ((size + sizeof(int)) & ~(sizeof(int)));

if ((size > 0) && (temp_index <= MAX_UNPACKED_MESSAGE_LENGTH))

{

ptr_to_memory_block = (void*)&wrapper->buffer[wrapper->next_free_index];

wrapper->next_free_index = temp_index;

}

return ptr_to_memory_block;

}When serial_alloc() is called for the first time, it sets next_free_index to the allocated size and returns the pointer to the beginning of the buffer:

next_free_index value and returns the address to the next chunk of data:

The

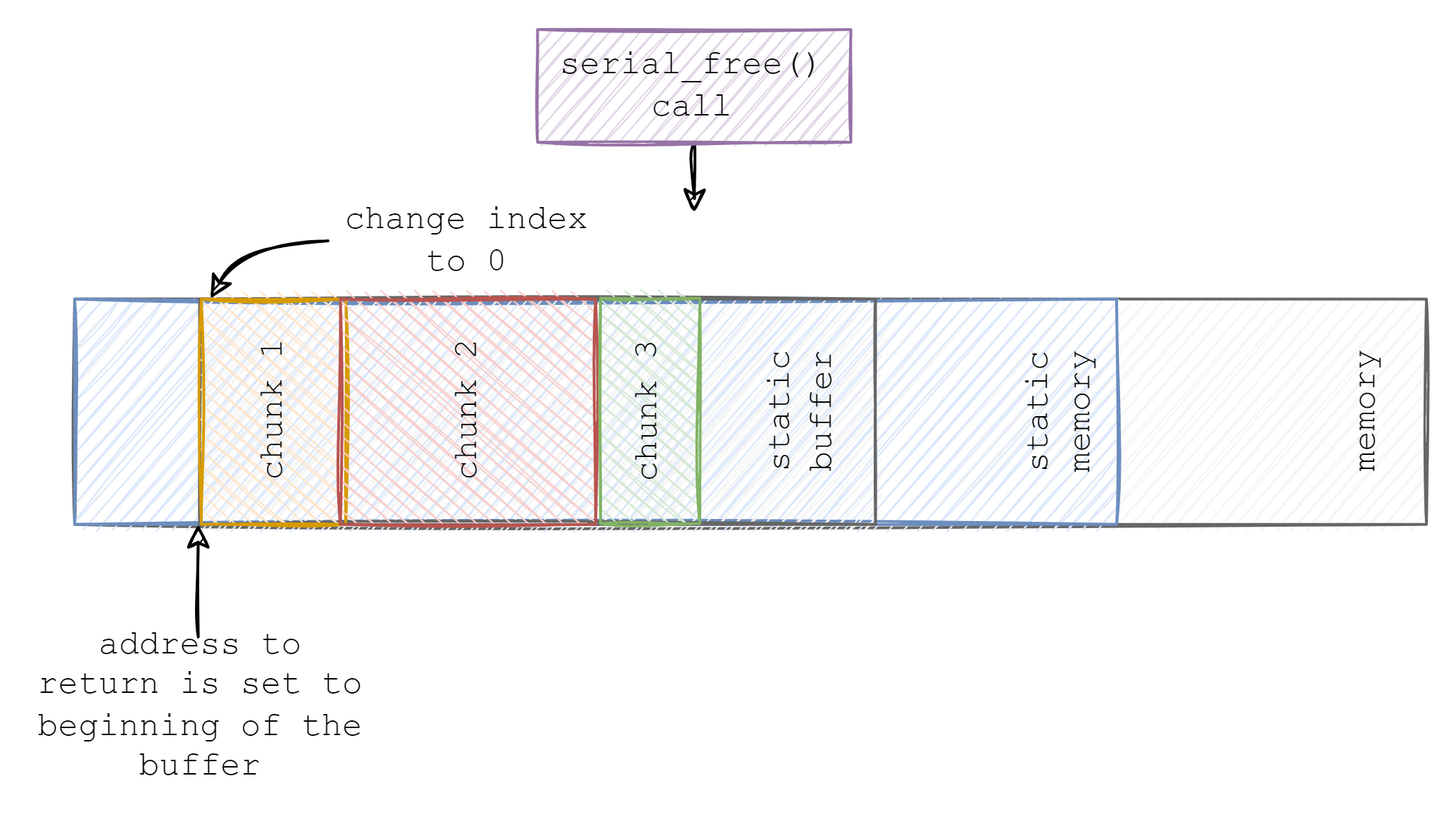

The serial_free() function sets the used buffer space to zero:

static void serial_free(void* allocator_data, void* ignored)

{

(void)ignored;

unpacked_message_wrapper* wrapper = (unpacked_message_wrapper*)allocator_data;

wrapper->next_free_index = 0;

}When serial_free() is called, it "frees" all memory by settings next_free_index to zero, so that the buffer can be reused:

![Serial free call]() Testing Implementation

Testing Implementation

The implementation was tested under Valgrind. To run the program under Valgrind type:

valgrind ./protobuf-c-custom_allocatorIn the resulting report, you will see that no allocation has been made:

==3977== Memcheck, a memory error detector

==3977== Copyright (C) 2002-2017, and GNU GPL'd, by Julian Seward et al.

==3977== Using Valgrind-3.18.1 and LibVEX; rerun with -h for copyright info

==3977== Command: ./protobuf-c-custom_allocator

==3977==

==3977==

==3977== HEAP SUMMARY:

==3977== in use at exit: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==3977== total heap usage: 0 allocs, 0 frees, 0 bytes allocated

==3977==

==3977== All heap blocks were freed -- no leaks are possible

==3977==

==3977== For lists of detected and suppressed errors, rerun with: -s

==3977== ERROR SUMMARY: 0 errors from 0 contexts (suppressed: 0 from 0)Summary

To write and use a custom allocator you have to:

- Determine the way how do you want to store your data.

- Write some kind of wrapper around your proto message type, and provide appropriate

alloc()andfree()functions replacements. - Create an object of your wrapper.

- Create

ProtobufCAllocatorwhich uses youralloc()andfree()replacements, then use allocator inx__unpack()function.

In this example, we:

- Decided to store data in contiguous, statically allocated block of memory (1)

- Wrote

unpacked_message_wrapperas a wrapper around protoMessageandbuffer, and provide replacements foralloc()andfree():serial_alloc()andserial_free()(2) - Created an object of

unpacked_message_wrapperon the stack, we named itout(3) - In

unpack_to_message_wrapper_from_buffer, we createdProtobufCAllocatorand filled it withserial_alloc()andserial_free()and passed tomessage__unpackfunction (4).

Tips and Tricks

If you work on a very memory-constrained system and every byte is gold, you can determine how big the MAX_UNPACKED_MESSAGE_LENGTH needs to be. For this, you can first set some arbitrary big-enough value for MAX_UNPACKED_MESSAGE_LENGTH. Then in serial_alloc, you need to add some instrumentation:

static void* serial_alloc(void* allocator_data, size_t size)

{

static int call_counter = 0;

static size_t needed_space_counter = 0;

needed_space_counter += ((size + sizeof(int)) & ~(sizeof(int)));

printf("serial_alloc() called for: %d time. Needed space for worst case scenario is = %ld\n", ++call_counter, needed_space_counter);

...For this sample case, we get:

serial_alloc called for: 1 time. The needed space for the worst-case scenario is = 32Things can get hard when the .proto message will become more complicated. Let’s add a new field to our .proto message:

syntax = "proto3";

message Message

{

bool flag = 1;

float value = 2;

repeated string names = 3; // added field, type repeated means "dynamic array"

}Then we add new entries to our message:

int main()

{

Message in;

message__init(&in);

in.flag = true;

in.value = 1.234f;

const char name1[] = "Let's";

const char name2[] = "Solve";

const char name3[] = "It";

const char* names[] = {name1, name2, name3};

in.names = (char**)names;

in.n_names = 3;

// Serialization:

message__pack(&in, pack_buffer);

...We will see this in the output:

serial_alloc() called for: 1 time. Needed space for worst case scenario is = 48

serial_alloc() called for: 2 time. Needed space for worst case scenario is = 72

serial_alloc() called for: 3 time. Needed space for worst case scenario is = 82

serial_alloc() called for: 4 time. Needed space for worst case scenario is = 92

serial_alloc() called for: 5 time. Needed space for worst case scenario is = 95So now we know, that this is our worst-case scenario. We need at least a 95 bytes-wide buffer.

In the real world, you generally want to set more space than 95, unless you are 100% sure and you tested it thoroughly.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Testing Implementation

Testing Implementation

Comments