Design patterns provide a set of proven solutions to common problems that arise during the design and implementation of ML systems. They provide a systematic approach to designing and building ML systems, which can lead to more robust and scalable systems that are easier to maintain and update. An ML pattern is a technique, process, or design that has been observed to work well for a given problem or task. ML patterns can help guide the development of new models, as well as provide a framework for understanding how existing models work. In this section, we'll cover patterns for data management and quality, data representation, problem representation, model training, resilient serving, and reproducibility.

Data Management and Quality

Effective data management and quality assurance patterns are crucial to building robust and scalable ML models. Ensuring that data is clean, versioned, and automatically validated helps in preventing model degradation and maintaining reproducibility. Below are key patterns for maintaining high data quality:

- Schema enforcement – ensures that incoming data adheres to a predefined structure, avoiding missing values or incorrect data types

- Data profiling – analyzes datasets to identify anomalies, inconsistencies, or missing values before model training, and helps in detecting silent data corruption early

- Automated data quality gates – implement CI/CD pipelines that run data validation tests (e.g., missing values check, drift detection) before allowing model training

- Data augmentation – applies transformations such as synthetic data generation, oversampling, or differential privacy-based augmentation to improve dataset diversity and robustness

- Automated data lineage tracking – establishes a data lineage framework to trace changes in data over time, ensuring transparency in data evolution and usage

- Bias detection and mitigation – identifies and mitigates biases in data by applying fairness techniques such as reweighting methods, adversarial debiasing, and differential subgroup evaluation

- Data validation – ensures data quality validations are automated (e.g., Write-Audit-Publish) to take place before data is published

While high data quality ensures robust model performance, tracking and maintaining this quality across multiple iterations and workflows requires an effective data version control strategy.

Data Version Control for Workflow Integration: Ensuring Reproducibility and Traceability

Modern ML workflows demand rigorous data tracking, much like software version control, as ML models are only as reliable as the datasets they are built upon. Unlike software development, where version control primarily tracks code changes, ML systems require data versioning, experiment tracking, and automated quality checks to ensure that models are built, tested, and deployed on consistent, high-quality data.

To effectively integrate data version control into ML workflows, organizations should look for solutions that offer:

- Immutable data snapshots – ability to track and restore previous dataset versions to maintain reproducibility

- Automated data lineage – capturing metadata about when and how datasets are modified, ensuring full traceability

- Seamless integration with ML pipelines – allowing smooth collaboration between data engineers and ML practitioners without disrupting existing workflows

- Scalability and performance – handling large-scale datasets efficiently, especially in cloud and distributed environments

- Data quality checks and governance – enforcing policies that ensure data consistency, completeness, and compliance with industry regulations

- Rollback and disaster recovery – providing mechanisms to quickly revert to stable versions in case of data corruption or drift

By adopting robust data version control practices, organizations can ensure that ML models remain reproducible, transparent, and compliant with industry standards, reducing risks associated with data inconsistencies and deployment failures. Patterns:

- Versioned datasets – use hashing-based versioning to track dataset changes, enabling reproducibility and rollback mechanisms

- Parallel experiment tracking – links data versions with experiment parameters, ensuring consistent comparison between multiple runs

- Data reproducibility framework – uses ML metadata stores to associate datasets with specific model versions, promoting traceability

Troubleshooting and Error Recovery With Data Versioning

When models underperform or fail unexpectedly, data version control enables easy root-cause analysis and instant recovery. Patterns:

- Rollback mechanisms – enable quick reversion to prior data states when new data leads to unexpected model behavior

- Incremental data versioning – stores lightweight snapshots of evolving datasets rather than full copies, improving storage efficiency

- Reproducible training runs – ensure that each training iteration is linked to a specific dataset version, facilitating consistent debugging and performance evaluation

Versioning Code, Data, and Parameters for Model Reproducibility

Reproducibility extends beyond models to data and parameters. Patterns include:

- Hyperparameter tracking alongside datasets

- Immutable storage of training data snapshots to prevent accidental modifications

- Git-like versioning for datasets, experiment scripts, and model weights to ensure reproducible experiments

Automated Data Quality Checks Before Production Deployment

To mitigate common ML deployment failures, automated data quality gates should be enforced before production. Patterns:

- Pre-production data validation – runs synthetic data tests and checks for feature drift before deployment

- Monitoring data pipelines – monitor feature consistency and detect anomalies continuously

- Fail-safe data pipelines – implement automatic retraining triggers when data distribution shifts beyond acceptable thresholds

- AI observability and alerts – integrate real-time anomaly detection to detect inconsistencies in incoming data

Data Representation

Data representation design patterns refer to common techniques and strategies for representing data in a way that is suitable for learning algorithms to process. The design patterns help transform raw input data into a form that can be more easily analyzed and understood by ML models:

- Feature scaling

- Scales input features to a common range, such as between 0 and 1, to avoid large discrepancies in feature magnitudes

- Helps to improve the convergence rate and accuracy of learning algorithms

- One-hot encoding

- Represents categorical variables in a numerical format

- Involves representing each category as a binary vector, where only one element is "on," and the rest are "off"

- Text representation

- Represents in various formats like bag-of-words, which represents each document as a frequency vector of individual words

- Other techniques: term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) and word embeddings

- Time series representation

- Represents using techniques like sliding window to divide the time series into overlapping windows and represents each window as a feature vector

- Image representation

- Represents in various formats, such as pixel values, color histograms, or convolutional neural network (CNN) features

These data representation design patterns are used to transform raw data into a form that is suitable for learning algorithms. The choice of which data representation technique to use depends on the type of data being used and the specific requirements of the learning algorithm being applied.

Problem Representation

These patterns are common strategies and techniques used to represent a problem effectively in a way that can be solved by a machine learning model:

- Feature engineering – selects and transforms raw data into features that can be used by an ML model

- Dimensionality reduction – reduces the number of features in the dataset

- Resampling – balances the class distribution in the dataset; helps improve the performance of the model when there is an imbalance in the class distribution

The choice of problem representation design pattern depends on the specific requirements of the problem, such as the type of data, the size of the dataset, and the available computing resources.

Model Training

Model training patterns are common strategies and techniques used to design and train machine learning models effectively. These design patterns are intended to improve the performance, scalability, and interpretability of machine learning models, as well as to reduce the risk of overfitting or underfitting:

- Cross-validation

- Assesses the performance of an ML model by partitioning the data into training and validation sets

- Reduces overfitting and ensures that the model can generalize to new data

- Regularization

- Reduces overfitting by adding a penalty term to the loss function of the ML model

- Ensures that the model does not memorize the training data and can generalize to new data

- Ensemble methods

- Combine multiple ML models to improve their performance

- Reduce variance and improve the accuracy of the model

- Transfer learning

- Uses pre-trained models to improve the performance of a new ML model

- Reduces the amount of data required to train a new model and improve its performance

- Deep learning architectures

- Use multiple layers to learn hierarchical representations of the data

- Improve the performance and interpretability of the model by learning more complex features of the data

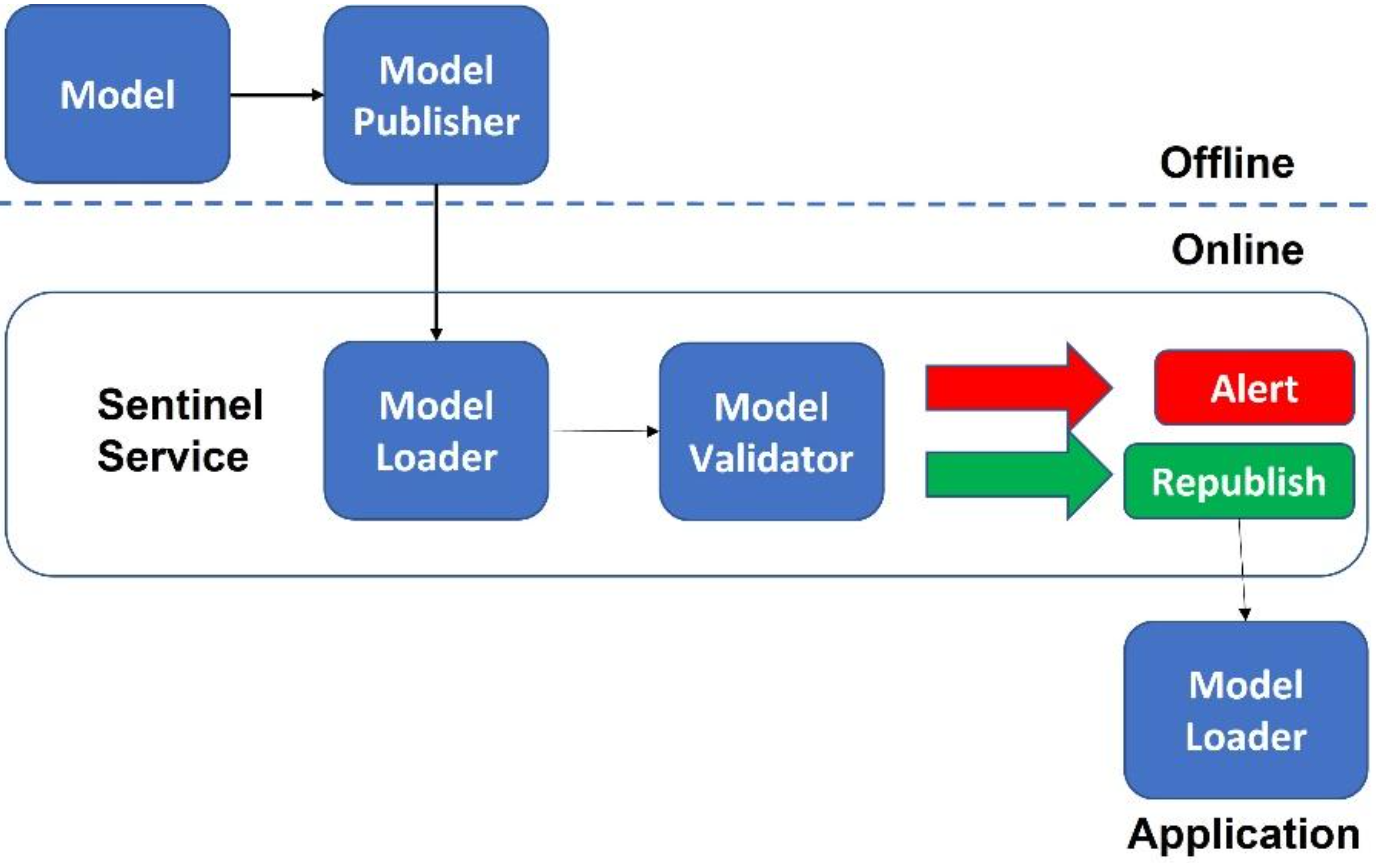

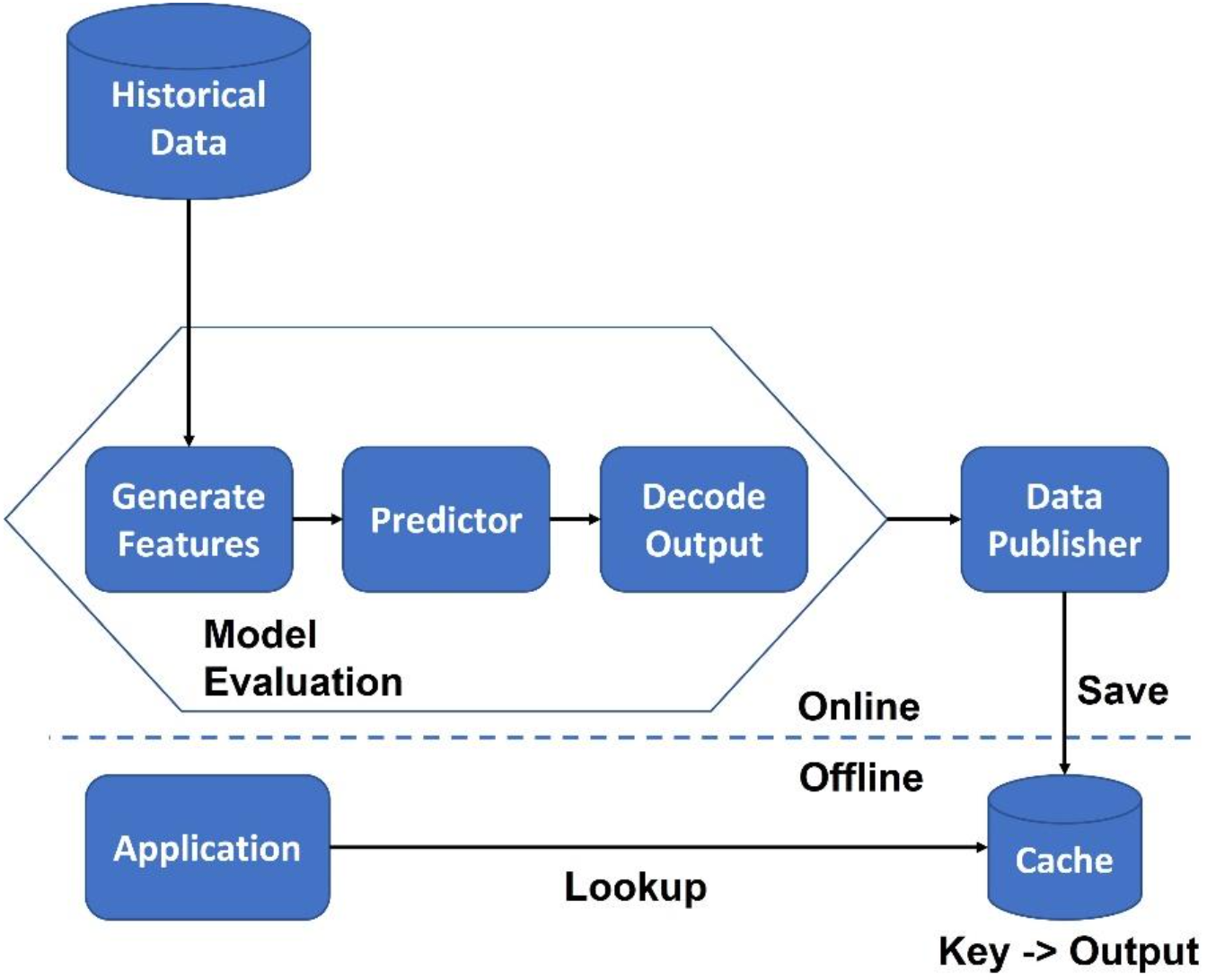

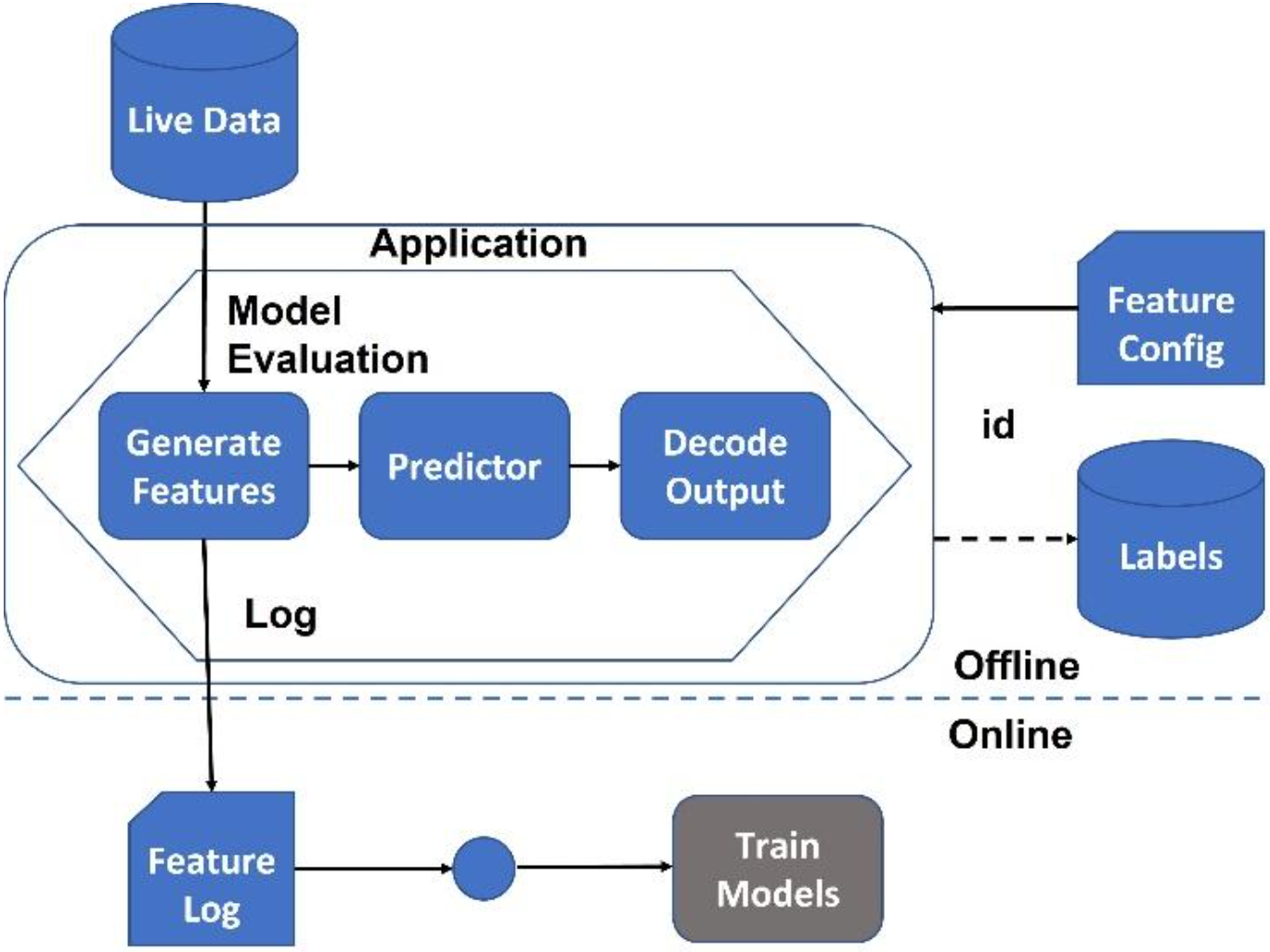

Resilient Serving

These patterns are common strategies and techniques for deploying machine learning models in production and ensuring that they are reliable, scalable, and resilient to failures. Resilient serving is essential for building production-grade ML systems that can handle large volumes of traffic and provide accurate predictions in real time. Patterns:

- Model serving architecture

- Overall design of the system that serves the ML model

- Common architectures include microservices, serverless, and containerized deployments

- Choice of architecture often depends on the specific requirements of the system, such as scalability, reliability, and cost

- Load balancing

- Distributes incoming requests across multiple instances of the ML model

- Improves the performance and reliability of the system by distributing the workload evenly and avoiding overloading any single instance

- Caching

- Stores frequently accessed data in memory or disk to reduce the response time of the system

- Improves performance and scalability of the system by reducing the number of requests that need to be processed by the ML model

- Monitoring and logging

- Essential for identifying and diagnosing problems in the system.

- Common monitoring techniques include health checks, metrics collection, and log aggregation

- Improve the reliability and resilience of the system by providing real-time feedback on the system's performance and health

- Failover and redundancy

- Ensure that the system remains available in the event of failure

- Common techniques include standby instances, automatic failover, and data replication

- Improve the resilience and reliability of the system by ensuring that the system can continue to serve requests, even in the event of a failure

The choice of design pattern often depends on the specific requirements of the system, such as performance, reliability, scalability, and cost.

Reproducibility [H3]

Reproducibility design patterns are a set of practices and techniques used to ensure that the results of a machine learning experiment can be reproduced by others. Reproducibility is essential for building trust in ML research and ensuring that the results can be used in practice. Patterns:

- Version control

- Tracks changes to code, data, and experiment configurations over time

- Ensures that the results can be reproduced by others by providing a history of changes and allowing others to track the same versions of code and data used in the original experiment

- Containerization

- Packages an experiment and its dependencies into a self-contained environment that can be run on any machine

- Ensures that the results can be reproduced by others by providing a consistent environment for running the experiment

- Documentation

- Essential for ensuring that the experiment can be understood and reproduced by others

- Common practices include documenting the experiment's purpose, methodology, data sources, and analysis techniques

- Hyperparameter tuning

- The process of searching for the best set of hyperparameters for an ML model

- Ensures that the results can be reproduced by others by providing a systematic and repeatable process for finding the best hyperparameters

- Code readability

- Essential for ensuring that the code used in the experiment can be understood and modified by others

- Common practices include using descriptive variable names, adding comments and documentation, and following coding standards

Avoiding MLOps Mistakes

Common mistakes and pitfalls that can occur during the design and implementation of MLOps are as follows:

- Model drift occurs when the performance of an ML model deteriorates over time due to changes in the input data distribution.

- To avoid model drift, regularly monitor the performance of the model and retrain it as needed

- Lack of automation occurs when MLOps processes are not fully automated, leading to errors, inconsistencies, and delays.

- To avoid this, automate as much of the MLOps process as possible, including data preprocessing and model training, evaluation, and deployment

- Data bias occurs when the training data is biased, leading to biased or inaccurate models.

- To avoid data bias, carefully curate the training data to ensure that it represents the target population and that is the data has no unintentional bias

- Lack of documentation occurs when MLOps processes are not well documented, leading to confusion and errors.

- To avoid this, document all aspects of the MLOps process, including data sources; preprocessing steps; and model training, evaluation, and deployment

- Poor model selection occurs when the wrong ML algorithm is selected for a given problem, leading to suboptimal performance.

- To avoid this, carefully evaluate different ML algorithms and select the one best suited for the given problem

- Overfitting occurs when the ML model is too complex and fits the training data too closely, leading to poor generalization performance on new data.

- To avoid overfitting, regularize the model and use techniques such as cross-validation to ensure that the model generalizes well to new data

By avoiding these MLOps mistakes and pitfalls, machine learning engineers can build more robust, scalable, and accurate machine learning systems that deliver value to the business.