Identity Federation and SSO: The Fundamentals

In this article, we will go over SSO fundamentals and dive into SAML and OIDC, empowering you to take part in the next conversation about it!

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeIn many software organizations, terms like authentication, SSO, and SAML are heard pretty often. Admittedly, many people will run away when hearing these terms, trying to avoid doing any authentication-related work.

In this article, we will go over SSO fundamentals and dive into SAML and OIDC, helping you understand why it is such a common topic and empowering you to take part in the next conversation about it!

What’s SSO and Why Do We Need It?

We are all familiar with the following screen and screens alike:

The technology behind them is called SSO (Single Sign On). As the name suggests, SSO is an authentication method that allows the user to sign in once (i.e., by entering their password) and connect to multiple applications.

This authentication method is very common for both individuals (i.e., logging into a Google account) and organizations of any size (i.e., logging into GitHub or Jira using your organization’s Okta deployment). For individual users, it has the advantage of convenience — users only need to sign in once, and they only need to remember one set of credentials.

For organizations, specifically IT administrators, SSO has the advantage of allowing central control of the authentication method. For example, they can enable two-factor authentication, add requirements on password strength, or use a smart card in order to sign in. Organizations deploying SSO may also benefit from a centrally managed user store; for example, when an employee leaves the organization, there is only one identity that needs to be removed.

In the examples above, the application used to log in, and the authentication service are developed independently. In order for this to work, both sides need to have an agreed communication method (a protocol). Applications that want to benefit from SSO, as well as SSO authentication services, will then implement their side of that protocol.

How SSO Systems Are Built

An SSO system consists of two types of parties:

SP (Service Provider) — The application the user is trying to approach. There are typically multiple service providers in an SSO ecosystem.

IDP (Identity Provider) — A system that authenticates users, maintains user sign-on sessions and is able to relay information about user identity and sessions to SPs. Simply put, an IDP offers user authentication as-a-service, i.e., Okta, Azure Active Directory, Google, etc.

A simple example of SSO is a user that browses eBay (SP) and is asked to authenticate via their Google account (IDP) when logging in.

Since the SP authorizes access to potentially sensitive resources based on the information it receives from the IDP, it needs to trust the IDP. The SP needs a way to restrict the IDPs that it is willing to work with to ensure the authenticity of the information it receives. This trust relationship is usually based on digital signatures issued by the IDP and verified by the SP — often by using a PKI certificate. It doesn’t matter which meaning is being used as long as the SP can be certain that the data is received from the IDP.

In addition to using digital signatures to ensure the integrity of messages, other mechanisms are employed to secure SSO protocols, such as nonce for preventing replay attacks and limiting the messages’ validity time.

The information that the SP ultimately receives from the IDP usually consists of a set of claims. A claim is simply a statement that a user has a given attribute. It can be the user name, email, groups it belongs to, etc. Claims may also refer to the authentication process itself, such as when the user's identity was last verified and how. At minimum, the set of claims should include one claim with a unique identifier of the user.

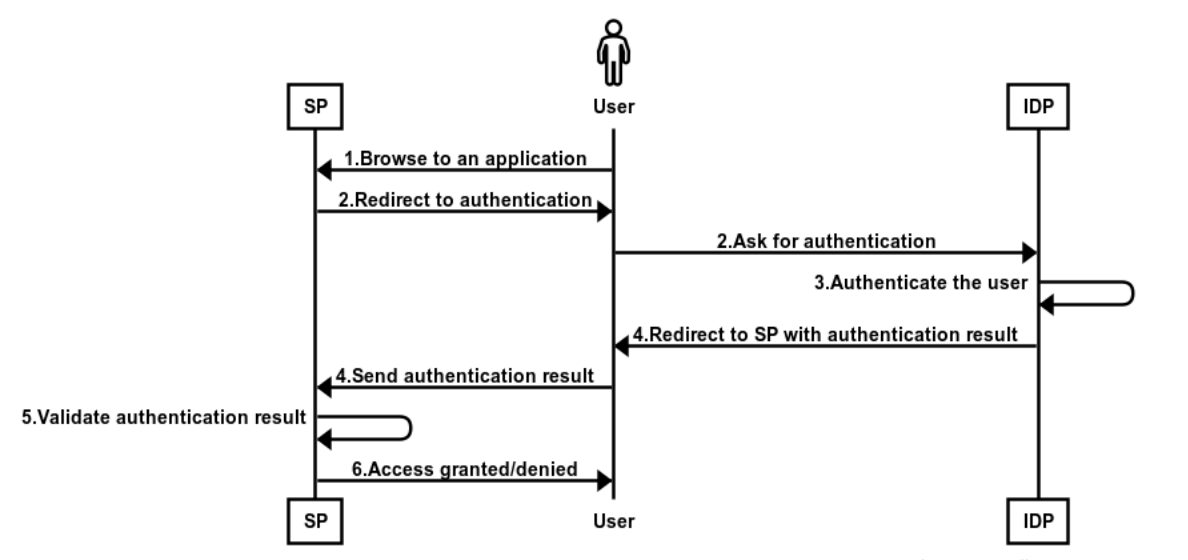

Having reviewed the fundamental requirements from an SSO system, we can now talk about an abstract SSO protocol. An SSO authentication process may be implemented with the following steps:

A user browses to an application they want to access (the SP).

The SP identifies that it needs to establish the user's identity. It then redirects the user to an IDP previously configured within the SP.

The IDP may either use a previously established authentication session or authenticate the user if such a session doesn't exist or has expired.

Once the IDP has reached a conclusion about whether there's a successfully authenticated user, it redirects the user back to the SP via their browser while passing (as part of the redirect response) information about the user or some sort of a handle that would allow the SP to securely retrieve one.

The SP validates the authentication result based on the trust relationship it has with the IDP.

Access granted (or denied). At this point, the SP might use the information they got from the IDP (the claims) for additional purposes. For example, authorization (use the claims to decide on roles and permissions).

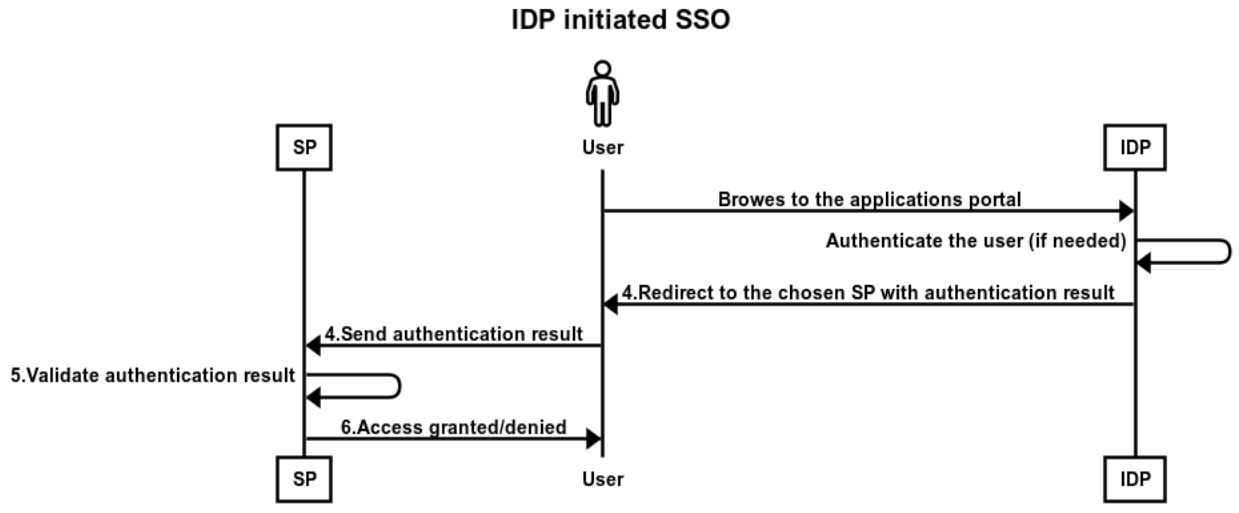

The protocol above describes an authentication process that is initiated by the SP (SP initiated). It is also possible to have a variation of this process, where the authentication is initiated by the IDP (IDP initiated). IDP initiated means that after the user logs in once, they will gain access to a portal, where they will have a menu of applications to log in to. By selecting an application, the user will be in step 4 of the above protocol — they will be redirected to the SP along with the authentication response. Then, all that remains is steps 5 and 6. The SP will need to validate the authentication results, and the user can be granted access.

Approaches to Authorization With SSO Login

As mentioned above, the IDP response includes various claims about the identity of the logged-in user and the authentication process itself. These claims may include details that can be used by the SP to authorize the user to perform specific operations within the application.

Such details may include groups the user belongs to, roles, or specific privileges. The SP might use this information for authorization purposes by mapping it to permissions within the app. When setting up SSO, on the IDP side, the organization might choose which information should be sent as part of the authentication response (for example, an organization may decide to include membership of the user in specific groups), and on the SP side, the organization will create the mapping to permissions (continuing the same example, by mapping groups to allowed permissions). Permission mapping can be made on a simple access level (read/edit/admin) or a complete ACL-based approach (group X has permission to see only a specific set of data, etc.)

A significant advantage of using one of the above approaches of authorization is that the organization might gain centralized control for authorization over different SPs. For example, an organization that uses an IDP, such as AD or Okta, allows administrators to review or change access to all SPs in use by the organization by changing the user's group assignment in the IDP.

SAML and OIDC

The abstract protocol described above is typically realized by using one of two standards: SAML and OIDC, which the IDP uses as a basis for identity management. An IDP might be based on one of these, but some IDPs support both, so it is useful to understand them both.

SAML is an XML-based protocol for exchanging security information. It is old, mature, and commonly deployed in enterprises. In SAML, SP-IDP trust is established using digital signatures based on the XML Signature standard.

OIDC stands for "OpenID Connect." It is a new and evolving protocol built off of the OAuth 2.0 protocol — a more general framework for open authorization protocols. OIDC uses backend-to-backend communication and signed JWT tokens to establish trust.

Don’t Roll Your Own SSO Implementation

When implementing an SP, we need to decide how to implement SSO support. After deciding which IDPs we are willing to connect to, we will need to decide which protocols to support and implement into our application.

Implementing SSO protocol support the correct way is a complex task — each authentication protocol consists of many small details, and missing just one might be enough to introduce a security vulnerability to the application. Having a secure application is an important part of ensuring its success, as it is difficult to gain customers’ trust and very easy to lose it.

Additionally, best practices and implementation details might change and evolve over time, especially due to security reasons. This means that there are maintenance costs hidden in the implementation of SSO protocols.

The intrinsic complexity of implementation, together with the disastrous potential impact that errors may have, suggest that rolling your own SSO implementation is often not the best idea — just like we typically opt for third-party implementations of encryption standards. This is further amplified by the fact that supporting multiple protocols is a common practice, which means that the costs and risks are multiplied.

Luckily, with the variety of 3rd party middleware that exists in the market, there is rarely a need to roll out your own solution for SSO. By plugging the middleware into your web server infrastructure, you can easily benefit from SSO interoperability while reducing the costs associated with implementing it.

Still, using a third-party SSO middleware is by no means an automatic guarantee that your authentication implementation is secure. Care must be taken to integrate and configure these solutions securely, and to do that fundamental understanding of the protocols is desirable.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments